|

Deborah Oropallo is an artist who consistently shocks and amazes. She doesn’t do this with violence or brutality. Instead, she does it subtlety, with images that challenge how we feel and think. While many conceptual artists rely on explanatory texts to support ambiguous visual statements, Oropallo makes her ideas explicit; so much so that they seem to be embedded in her materials at an almost cellular level.

I first saw Oropallo’s work in 2001, at her San Jose Museum of Art retrospective, How to: The Art of Deborah Oropallo. There, she took abject subjects — 55-gallon drums, canisters of gas, nylon rope and a variety of other derelict industrial objects – and transformed them into something exquisite. The drums, for example, she painted bright orange and turquoise and presented them in cellophane, like shrink-wrapped gifts whose lurid colors recalled the toxic waterways documented by photographer Edward Burtynsky. But unlike the realities Burtynsky documented, Oropallo’s fictions made the banal iconic, and it was unnerving. Having lived and worked in Silicon Valley, I knew the chemically tainted environment of these objects all too well, and I was shocked to see them in a museum, much less in one so close to areas where local groundwater had been contaminated. But more than anything, I was struck by how beautiful these paintings were and how strongly I was attracted to them. This uneasy, bifurcated reaction was further complicated by Oropallo’s seamless mixture of painting and photography.

|

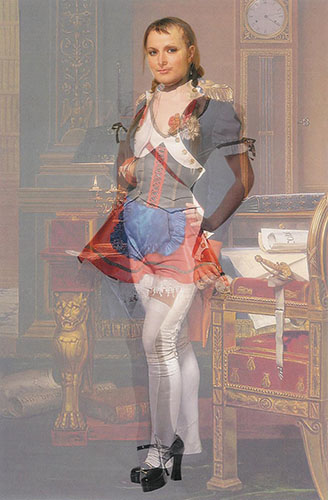

I later experienced an even more disquieting juxtaposition of real and unreal at Guise, Oropallo’s 2007 show at the de Young Museum. There, she grafted the faces and bodies of female models onto reproductions of 17th and 18th century portraits, the originals of which depict men and women in Napoleonic-era garb flashing displays of wealth and power. There was talk about them being symbols of female empowerment. But there was quite a bit more going on. By today’s standards, the men in the original paintings, with their tights, wigs and high-heeled shoes, seem positively effeminate – a fact that Oropallo exploited to demonstrate what the world might look like if humans were truly hermaphroditic.

|

The pictures had a gauzy, now-you-see it, now-you-don’t quality. They seemed to shift in and out of focus like anamorphic images, making it easy to think that if viewed from a certain angle the figures might suddenly reveal their true nature: male or female. Instead, they clung to their Middlesex status, creating the eerie possibility that Oropallo’s digital sleight of hand might somehow be capable of incarnating their biological equivalents in real life.

|

|

|

sounds so intriguing–I feel like catching that exhibit! J