|

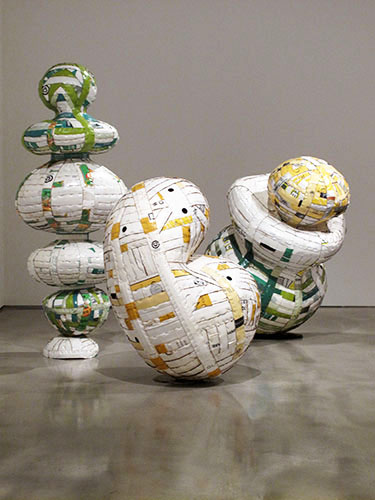

Now that “re-purposed” has officially replaced “eco art” and “green art” as the preferred term to describe objects filched from the trash to make art, one wonders: do we really need a new word to denote a practice as old as Duchamp? Don’t answer. Just see "Afterlife", a show built from recycled junk at SJICA.

In 2008, guest curator Kathryn Funk (a former SJICA executive director), mounted a similar show in vacant San Jose storefronts that included three of the nine artists on view here. Her goal, then and now, wasn’t to make a political statement; it was to showcase artists who were deeply engaged with their materials. That such engagements light up social, political and environmental themes without being swamped by ideology demonstrates how really good, socially relevant art can spring from relatively narrow (and often highly idiosyncratic) personal investigations. As such, Afterlife may be the perfect antidote to another credit-flexing, landfill-breeding holiday season.

|

|

|

|