|

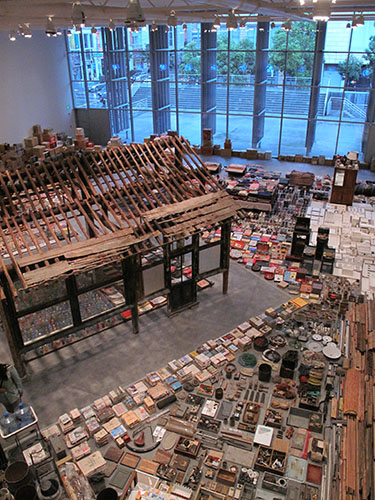

The project is by now legendary: Beijing artist Song Dong, long known for acts of art that are quiet but socially resonant interventions in Chinese order, power, and tradition, helped his aging mother, Zhao Xiangyuan, to resolve her grief over the loss of her husband by organizing and exhibiting the thousands of everyday household items she began recycling during the 1950s and then continued hoarding for the rest of her life. The resulting installation, Waste Not, curated by art historian Wu Hung, was originally shown in 2005 at Beijing-Tokyo Art Projects in the still-raw 798 arts district of Beijing. Since then, it has traveled to such venues as the Guangju Biennale, the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and, now, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. Along the way, the installation’s form has remained more-or-less the same: a skeletal outline of the artist’s diminutive boyhood house, composed from its actual remaining timbers, windows, and roof poles, as well as a floor-scape of meticulously organized rows, stacks, and sections of what seems like a lifetime of the contents that once filled the house: clumps of colorful string, empty plastic bottles, extra bottle caps, squeezed-out toothpaste tubes, recovered buttons, used Styrofoam food containers, rows and rows of worn and worn out shoes, washed-in and washed-up wash basins, and every piece of exhausted clothing that may once have fit a child.

|

|

|

.jpg) |

|

|

|

Any of us who have sorted through our mother’s belongings after her death, trying through grief to decide what to do with them – tearful smiles brought on by a coffee can packed with rubber bands – can relate to this installation of the most ordinary (abject, really) things collected by that person at the center of consciousness, the mother. This show made me overwhelmingly sad. A man’s representation of his mother that seemed to be wholly missing the poetics/imagination of the “crazy” woman who died trying to help a wounded bird.