by Maria Porges

|

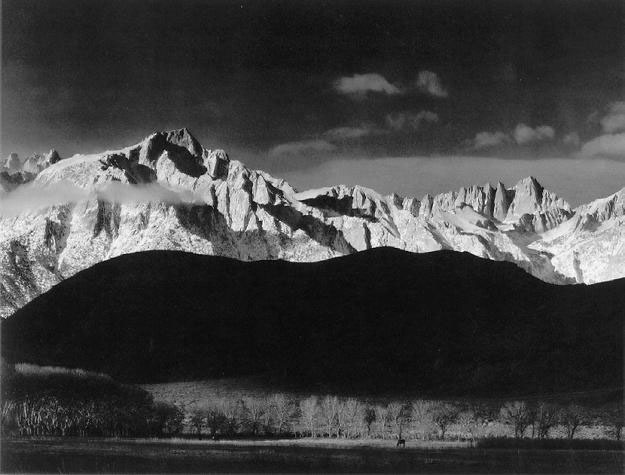

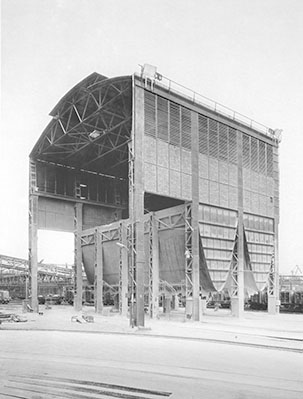

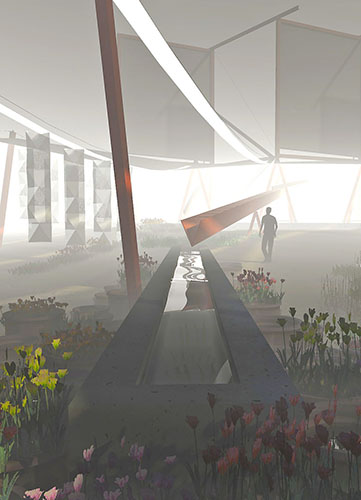

Some museums try to be all things to all people, exhibiting everything from costumes and ancient Egyptian artifacts to works made last year. But a number of mid-sized institutions eschew the global approach, opting instead for a tighter focus. The Nevada Museum of Art in Reno is one such institution. Its programming, collecting and exhibitions examine the landscape, specifically, human interactions with the natural, built and digital environments. This innovative and highly successful approach has produced a meaningful and dynamic relationship with the institution’s setting: the extraordinary desert landscape of northern Nevada—as well as with Land Art’s history throughout the American West.

|

|

|

|

|