|

In 1954 a salad oil magnate and self-educated painter/theorist named Jiro Yoshihara issued a challenge to Japanese artists. “Do what has never been done before!” Making that declaration against the ruin that was Japan after WWII, he urged artists to commit to changing human culture, imploring them to unleash the human spirit through “the scream of matter itself.” Spiritual liberation pursued in such a manner, he believed, could deliver Japan from the circumstances that led to its undoing.

|

When Yoshihara died in 1972 and the group disbanded, it had swelled to 58 artists spanning two generations. Though it was scarcely known to the general public during its existence, its art-world cachet couldn’t have been greater. The roster of American and European artists, critics and collectors who visited the group’s Osaka headquarters reads like a who’s who of postwar art. It included: John Cage, Peggy Guggenheim, Yoko Ono, Jean Tinguely, Merce Cunningham, Sam Francis, Clement Greenberg, Willem De Kooning, critic Lawrence Alloway and MOMA curator William Lieberman to name but a few. Crosspollination had indeed occurred, and before the ‘50s ended, Yoshihara’s dream of an international association of like-minded artists had been realized. Yet it remained, for the most part, an underground phenomenon.

|

, 1954.jpg) |

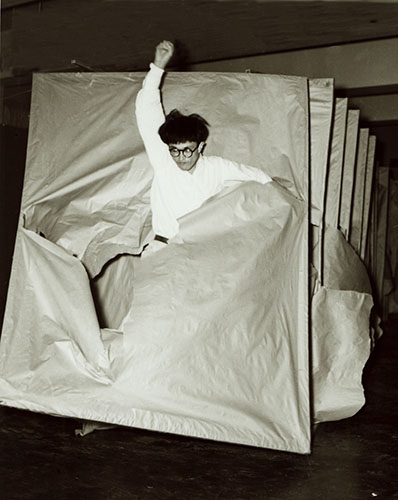

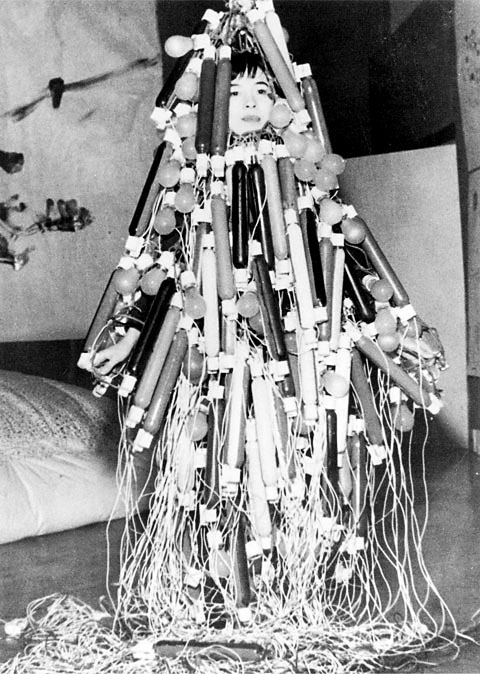

The most memorable show Gutai artists painting with a bicycle, an umbrella, a watering can, a toy car and other unconventional implements, surpassing in bodily engagement Jackson Pollock while and running on a parallel track with Yves Klein who made body prints called “anthropometries.” In clips of the installations we see Gutai artists engaged in other boundary smashing activities: wrapping outdoor spaces in fabric and suspending inflatable puppets and tubes of colored water from trees, prefiguring land artists like Christo, Guiseppe Penone and Andy Goldsworthy. Of the stage performances, those that lodge in memory are Akira Kanayama’s placement of a dirigible-like inflatable before a seemingly shocked crowd, and Shiraga’s Ultramodern Sanbaso in which he dons a cone-shaped hat and a suit with wing-like arms, reminiscent of the one Swiss Dada founder Hugo Ball wore at the Café Voltaire in 1916. Missing from this collection are clips from Expo ’70 which would have shown Gutai at its technologically most sophisticated.

|

_V2.jpg) |

|