by David M. Roth

|

Is Michael Jang the greatest living Bay Area photographer you’ve never heard of? I’m betting he is. Like many artists, Jang, 61, made commercial work to earn a living while quietly pursuing art. He never intended to show it. A soft-spoken, unassuming man, he found galleries off-putting. That, apparently, has changed. Earlier this year, SFMOMA, which acquired a trove of his photos, placed two images from his paparazzi series, Banquet Crasher, on view next to photos by Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. Both influenced Jang while he was earning BFA and MFA degrees at Cal Arts and SFAI in the 1970s. Like them, Jang has a knack for framing decisive moments packed with details that make you look and keep on looking.

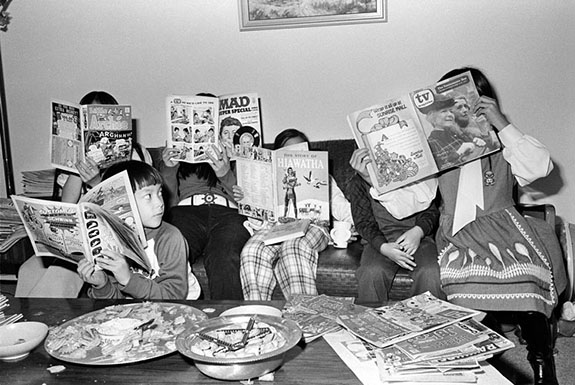

This show, The Jangs, is an intimate family profile made in 1973 while he was enrolled in an SF State workshop taught by Lisette Model, Diane Arbus’ teacher. The 30 black-and-white prints on view detail Jang’s aunt, uncle and cousins in their suburban cocoon: watching TV, eating, goofing, exercising and lounging amongst telling period artifacts. At a time when America’s leading street photographers were depicting a culture at war with itself, Jang’s views of life in the upscale SF suburb of Pacifica cut against the grain. They could be stills from a cheery sit-com about Chinese-Americans. Portraits of assimilation and success, these pictures smash whatever stereotypes might have then existed.

|

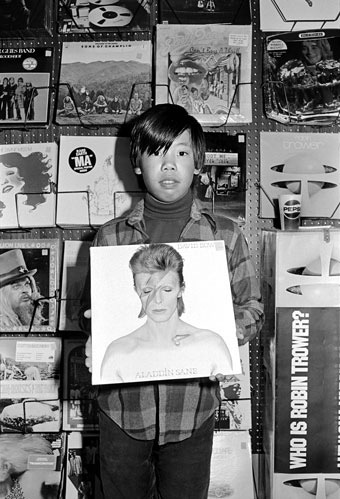

While the Westernization of China and Chinese culture is today a fact, it wasn’t back then. So when we see Jang’s uncle wearing a visor and cowboy boots; the family posed in dark glasses as Devo fans; his young cousin standing before a wall of football posters or iconic ‘70s LPs, we know we’re no longer in Chinatown. Jang maintains that he made these pictures as casual snapshots, with no documentary intentions, and I believe him. But we also know that artistic choices aren’t always conscious acts. Why, for example, did Jang make a picture of David Carradine in his Kung Fu role staring out from a TV screen in the Jang's living room? My guess: The appearance of this faux-Asian screen star signaled a pivotal moment in the mainstreaming of Asian culture in the U.S., and Jang clearly recognized it. Evidence of actual Chinese culture in the series is similarly scant; it is confined to exactly one image: of a disembodied hand pointing to a rice cooker, then an exotic item in American kitchens. It’s an anomaly within the series, but it doesn’t dilute Jang’s essential message, which is: These are Americans, no hyphenation required.

.jpg) |

Still, Jang’s photos contain enough weird ticks to push them into Winogrand-Friedlander territory. What, for example, can we make of that headless “body” in Chris Skiing in the Living Room? Clothing minus the mannequin? It’s a possibility since the family owned a chain of leather goods stores. But what about the one of the boy drinking a bottle of Dr. Pepper through a funnel while dad looks on through a window? And why is Uncle Monroe practicing his golf swing in the dark? They’re outliers in this series, but within Jang’s oeuvre they are emblematic.