by David M. Roth

|

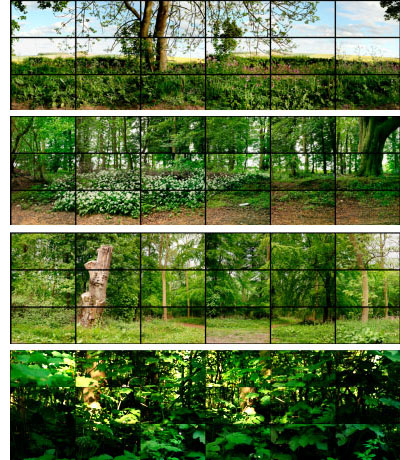

Conventional views of the world, whether supplied by painting, photography or cinema, have always frustrated him. In response, Hockney has used a wide variety of technologies and media to expand it. One of the most potent salvos in this exhibition-cum manifesto is Seven Yorkshire Landscapes. It consists of 18 video monitors in the museum’s first-floor lobby, each of which displays moving fragments of a different outdoor panorama. The effect is akin to traveling through the English countryside in a slow-moving vehicle outfitted with a huge partitioned window. Short and color-saturated,

|

These videos recall, at first glance, moving versions of Hockney’s Polaroid grids from the ‘80s: each an orderly right-to-left procession of neatly segmented views. Or so we think. Look closely and you’ll see trees splitting apart and reconnecting, swatches of foliage moving at speeds different from those in adjacent frames, as well as unexpected things, like a background that remains static while everything else in front of it moves. These aren’t just technological somersaults. They’re Hockney demonstrating that consciousness is a bit like a dog’s nose: a roving free-range sensor that catalogs the world by instinct. Needless to say, this is not how art typically represents reality.

|

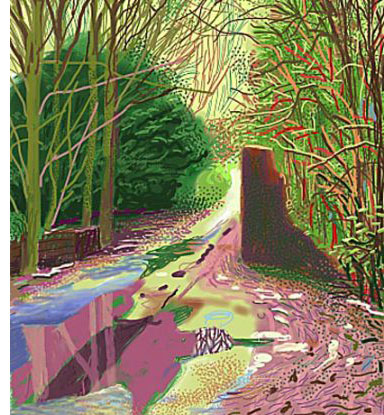

The most powerful examples are clustered at the far end of the basement gallery. May Blossom on the Roman Road, with its strong shadows, Van Gogh swirls in the sky and pointillistically daubed flowers feels almost hallucinatory. So does Bigger Trees Nearer Warter, where a towering block of bare branches, framed by converging roads, assumes architectural proportions that stop just shy of physical intimidation. Woldsgate Woods, 6 & 9 November 2006, a six-canvas painting in which the earth is painted persimmon orange, combines views of the same area recorded at different times of day, resulting in shadows that fall in directions and at angles you would not see in a picture designed to encompass a smaller chunk of time. It is but one example of many such paintings that deal with time and how the brain might register it if humans weren’t burdened with what Hockney calls a Cyclopean viewpoint: the form of binocular vision that affords us the rough equivalent of what can be seen through a 50-millimeter camera lens.

|

|

caricature reminiscent of high school stage sets. The good news is that it’s flanked on three sides by some of the most innovative, most technologically adventuresome pictures Hockney has made: 12 iPad drawings, each measuring 93 by 70 inches. If you think his large oils evince a visionary quality, these are exponentially richer. They capture spring with preternatural resplendence. The colors are massively exaggerated – over sweetened fuchsias, magentas, chartreuses and the like — but the hyperbole seems acceptable, even welcome. Why? It’s the iPad. It perfectly captures the movements of Hockney’s hand while cloaking the physical evidence of it. That, you might think, would be grounds for dismissal, but it is not. The appeal has to do with the tension between the virtual and the real, and with all of the jangly lines and hyperkinetic marks that give off the energy of light contrails captured in a time-lapse photo. For an artist long accustomed to working with brushes and pigment, Hockney seems to have had little trouble squeezing every last pixel-droplet of possibility from the new media; he bends its limitations, whatever they are, to his own ends.

In A Bigger Yosemite, where the pictures measure nine feet tall and the colors are appropriately more muted, the textures of his marks and line are as wide-ranging as the views depicted. They run from crude to highly granular. Thumb and finger smudges, for example, define mountain peaks and gorges; pinpoint lines make pine needles glow like illuminated Christmas ornaments. Other electronic sleights of hand convincingly mimic chalk pastel. All totaled, they enable Hockey to turn Yosemite’s well-known splendors — its misty waterfalls, towering peaks and flowering meadows –into arguments for a fresh approach to image making.

|