|

|

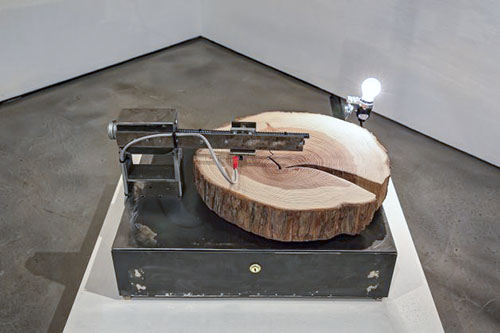

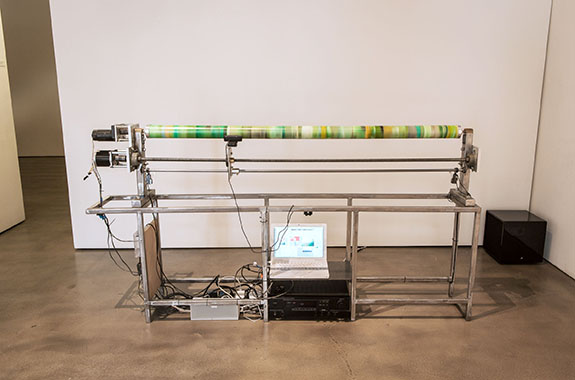

At the Laboratory for Tree-Ring Research in Arizona, for example, she learned that trees hold vast quantities of chemical, hydrological and geological data. So, too, do core samples of the Earth’s crust. In her art, those facts remain largely in the background. The installation, Log-rhythms, in which tree rings spin like vinyl platters, comes off as a seriocomic exercise. The electronically generated noises hint at scientific inquiry, but the installation, which occupies the gallery’s back room, feels more like a poke at animism: the primitive belief that all things, living and inanimate, contain spirit. Her core samples offer a similar jest. She creates them by pouring plaster and dye into skinny cylinders which, when filled, resemble layers of ice cream permeated by different flavors of syrup. They hang like newspaper scrolls from wall hooks. When taken down and “played” like a pianola roll with a microscopic camera, two things happen. Sounds fill the room at irregular intervals and recorded data becomes source material for large prints. Nine vertical scrolls cover an entire wall; while two others, far larger, stretch across pulley-like contraptions that reach almost to the ceiling. Carrying the populist Woody Guthrie song-title slogan, This Land is Your Land, they look like tie-dyed fabric inscribed with moiré patterns. They’re vivid but not easily apprehended. Like Strontium, Gerhard Richter’s monumental photo installation at the de Young Museum, they are impossible to bring into focus, and as such, they exemplify the postmodern notion that facts are, at best, shifting approximations determined by

|

perspective. They also, on account of their toxic colors, align Berlier with eco-oriented artist/scavengers like Hanna Kunysz who, last year, displayed columnar sculptures built of plastic trash that were seen as portents of environmental meltdown. Like many Bay Area artists, Berlier has spent significant time gathering material at San Francisco’s recycling facility, Recology.

|

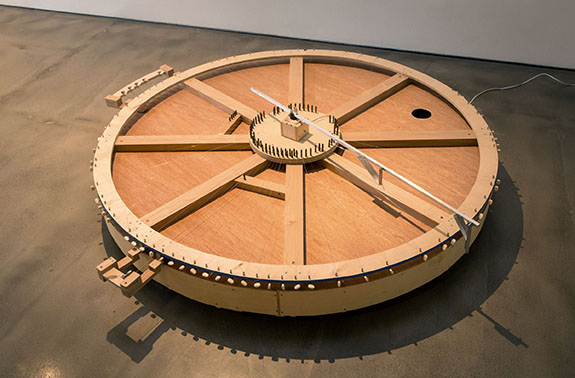

Another prominent theme in the show is time. Standard Time, a circle of 24 cyanotypes onto which a moving beam of light is projected onto images of rail tracks, deals with how, before railroads, every locale in America adhered to its own clock, a situation that demanded synchronization if schedules were to be operable. A less obvious, but equally intriguing aspect of this display is how trains changed the human experience of space and time. As Rebecca Solnit points out in her biography of Edweard Muybridge, it wasn’t the photographer’s invention of the zoopraxiscope, a forerunner of motion pictures that introduced the concept; it was the train. It did so by moving people through the landscape, framing and reframing it for a filmic effect that presaged movies. Or so Solnit’s argument goes. Its resonance here lies in the fact that the railroad magnate, Leland Stanford, whose university now employs Berlier, funded Muybridge’s research, which proved, among other things, that a running horse has all four hooves off the ground, a fact then unknown. Standard Time, which runs as a loop, feels like a tribute to these long-ago events.

|

The exhibition concludes on a personal note, with an installation inspired by the artist’s aunt who, at age 84, revealed in a letter that she was gay. To Berlier, who is openly gay, that information came as no surprise — her aunt lived most of her adult life with another woman. The surprise was how directly and articulately she described why she acted on her desires. It’s a literary event that here takes on theatrical proportions thanks to Berlier’s decision to hire an actress to read the text. The recording is accompanied the projection of a silhouette of a rocking chair moving back and forth. Both appear in a long narrow hallway pierced by a ray of light, a fitting backdrop for a story of self-liberation, recollected from an era when doing so held far greater risk than it does today. The title, I Would Not Change It, is the letter’s last sentence. I’d apply it to the whole exhibition.

This was one of my favorite exhibits in a long time. From concept to execution it was exceptional.