|

|

Murray ignored such voices. She painted on wildly shaped, multi-part canvases whose contorted forms gave off a gyroscopic energy, but on close inspection, revealed domestic scenes being blown apart, as if struck by a tornado engineered by Picasso working hand-in-glove with Maxim Gorky, Jean Arp and a crew of wrecking ball cartoonists. Into her paintings Murray emptied the detritus of her life and her unconscious, merging the two in works that mixed representation and abstraction. She took everyday objects – shoes, chairs, tables, coffee cups — and transformed them into a messy, autobiographical, decidedly female vision, absorbing what she needed from early and mid-20th century Modernism, engaging in the necessary debates about flatness, surface, color and support structure, and arriving at a synthesis that was as adamant about asserting materiality as Minimalism was about denying it.

.jpg) |

|

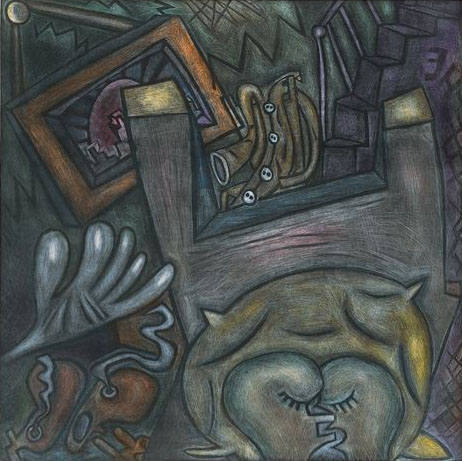

Other notable examples include Lovers, a small square drawing that depicts an interior scene from an overhead viewpoint. The couple, eyes and mouths streaming smoke, is watched over by a weirdly disfigured torso. Everything else in the room is spatially unmoored. Cracking Cups, built of ovoid and circular forms, shows Murray’s talent for distorting and reassembling. This concatenation of shapes more closely resembles a bomb cleaved by a bolt of lightening– a far cry from the staid domesticity we typically associate with the source imagery, coffee cups. It crackles with energy. Undoing, with is swirling Mobius strip, feet and legs akimbo, upended wine bottle, and open vortex at center, all but exerts the sensation of physical suction. Over and over, Murray transforms a vocabulary of repeated forms without actually repeating herself. While Gris-like edge shadowing gives many of these paper works a distinct family resemblance, the compositions are as different from each other as are the monumental shaped canvases that ground this show. The latter demonstrate what gave Murray, at age 40, the impetus to begin making paper perform unnatural acts.

.jpg) |

Greenbergian formulation. Murray did the opposite. She painted 3-D biomorphic forms that overflowed with feeling.

Thanks David…we are plannning to see this show very soon…

Eileen