|

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

exchange, Guggenheim agreed to give Bauer a baronial house on the Jersey shore, a Duesenberg and $300,000 payable in annual installments of $15,000. After signing the contract, Bauer claimed he’d been duped, blaming his poor command of English for blinding him to the meaning of the word “output”. Bauer wanted the agreement nullified. Guggenheim and Rebay, the museum’s director, refused. Acrimony andlawsuits ensued. Bauer took revenge by not painting again after 1940. He died in 1953 at age 64. None of these events, however, stopped Rebay from continuing to hype Bauer, nor did it deter the Guggenheim Foundation, as it later became known, from exhibiting his works. That all changed when the Guggenheim Museum opened in the new Frank Lloyd Wright building in 1959, ten years after Solomon Guggenheim’s death. Weary of the saga, the museum, under his son Harry’s directorship, forced to Rebay to resign. It consigned Bauer’s works to the basement and sold them off quietly over the years. More than half century later, Bauer remains a touchy subject at the museum. In 2005, when it mounted a revival of The Art of Tomorrow, Rebay’s first exhibition for the Museum of Non-Objective Painting, Bauer was relegated to a supporting role.

.jpg) |

sweeping European art: Eastern and Western mysticism, the Theosophical writings (on “thought forms”) by Annie Besant, Charles W. Leadbeater, Rudolph Steiner and others who sought to penetrate the surface of physical reality to get at pure spirit. In that regard, Kandinsky’s own writings are notably famous, but he was hardly alone. The quest for an object-free vision encompassed nearly all of the Russian avant guarde, the De Stijl painters, Jean Arp, Mondrian, Hilma af Klint and Frantisek Kupka to name but a few. Mardsen Hartley, Arthur Dove and Georgia O’Keeffe were among the Americans pursuing similar goals. As for Bauer, he issued his own writings on the subject: Cosmic Movement (1918), aligning the meaning of art, music and cosmic forces, and Manifesto of Painting (1921).

|

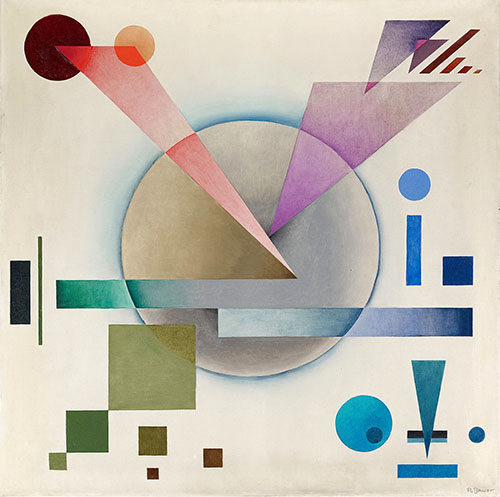

Larghetto III (1919) breaks free of representation with cryptic symbols painted on translucent fields of color. The musical title, one of many Bauer used, reflects an interest in synesthesia. The concept, applied to painting, was that color could be a gateway to sound and to pure feeling, an idea that would become more important for Bauer and Kandinsky during the ‘30s when they moved, in tandem, toward a utopian-oriented geometry.

|

century where the future was imagined as being filled with pyramids, obelisks, monorails and space needles. “God geometrizes” is a Plato maxim that was widely circulated among artists in Bauer's day, and I have no doubt that he believed it. Though such visions now seem somewhat dated, early Modernism’s recasting of “sacred geometry” continues to cast a long shadow, evidenced by Minimalism and by the ongoing vitality of the cosmic-leaning Light and Space movement where formlessness and color are the essence of what is, essentially, a spiritual practice.

Where Bauer’s career might have gone had he not cut it short is unknown. One thing we do know: While Bauer’s contributions were excised from art history, his work continued to circulate widely after his death. The catalog for Weinstein’s initial Bauer retrospective lists 26 group shows and 17 solo exhibitions between 1953, the year of his death, and 2007. Many were in prominent museums, here and in abroad. They include three group exhibitions at the Guggenheim, one at the Whitney (The American Century: Art and Culture, 1900-1950) and another at the Société Anonyme’s Modernism for America, which, from 2006 to 2010, travelled to the Armand Hammer Museum, The Phillips Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, Frist Center for Visual Art and Yale University Art Gallery.

In other words, Bauer has been hiding in plain view for more than 50 years. Why he remains a shadow figure is a mystery. The mature work he left behind argues for reevaluation.

A very informative, well-researched, and well-written review.

Thank you, David,

“…tempting to cast Bauer as a Kandinsky acolyte…”…. on the nose there…..