|

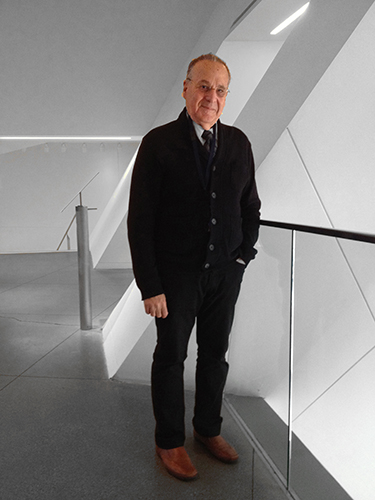

After serving eight years as curator of UC Davis’ Nelson Gallery, Renny Pritikin, in April, was named chief curator of the Contemporary Jewish Museum. He spoke with Squarecylinder Editor and Publisher, David M. Roth, at his office on August 14.

|

I’ve obviously thought about this a lot. Every job I’ve had has parameters, I’ve realized, even my first job at New Langton Arts. It was about creating a safe place for truly experimental work – performance, installation, video – that didn’t have a home, and connecting artists directly with their audience, which was other artists in that very small institution. So those were the parameters I came up in; they were very narrow if you step back and think about it. I was there for a decade, and then I get this job at Yerba Buena, thinking I know it all, I’ve got all the answers, I’ve got it all figured out. And I go into an institution where very quickly I realize I have to throw out every thing I thought I knew and learn how to look at multicultural forms and learn how to curate against my own taste sometimes or use my eyes to evaluate things I didn’t have to before. So I really had to expand my understanding of what contemporary art was at Yerba Buena. I developed this mix of three things: fine art, popular culture and community art. I did a lot of shows where I juxtaposed a hot New York artist and a tattoo show and work from the halfway house around the corner. That was a deliberate provocation to the contemporary art world to say, let’s look at all this stuff equally.

|

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Renny is an amazing and inspiring curator, for whom I now have even more respect. Thanks David, for publishing this.