by David M. Roth

.jpg) |

A conceptualist before the term was coined and an irrepressible shape-shifter whose career flipped restlessly between media, Bruce Conner (1933-2008) was one of the most incisive artists to have emerged from the Bay Area. Though his work roamed widely — from spiritual abstraction (in the mandala drawings) to Funk (in his nylon-stocking wrapped assemblages) and to withering critiques of American culture (in his films) – these seemingly distant poles of his practice were united by his desire to penetrate life’s mysteries and to resist anything that might get in the way. Ironically, the resistance Conner encountered helped spawn the conceptual side of his art, which took the form of serious pranks that speak just as strongly to issues of value, authorship and authenticity today as they did during his prime in the 1960s and 1970s.

Conner would spend his life trying to unlock those secrets. The search would lead him from his home in Wichita to Beat-era San Francisco and, subsequently, to Eastern religious philosophy, psychedelic drugs, rock music, politics and to close associations with many of that era’s most important figures, among them the poet Michael McClure. Representative samples from these efforts can be seen in Somebody Else’s Prints, an exhibit of works on paper organized by the Ulrich Museum of Art in Wichita, so named for Conner’s career-length penchant for deflecting the spotlight away from himself. Though it excludes key pieces of the Conner

|

oeuvre –the experimental films, the ghostly photograms and the nylon stocking-wrapped assemblages of detritus – it shines valuable light on other equally important aspects of Conner’s artistic persona: the felt-tip pen mandala drawings (1963 to 1971); the collages made from 19th century magazine engravings; and the inkblot pictures. Also on view in the ICA show are books, a tapestry, photos, a scaled-down light show and much memorabilia. Collectively they form a tantalizing snapshot of the artist’s multifaceted career, which in 2016 will be the subject of a full-scale retrospective at SFMOMA.

.jpg) |

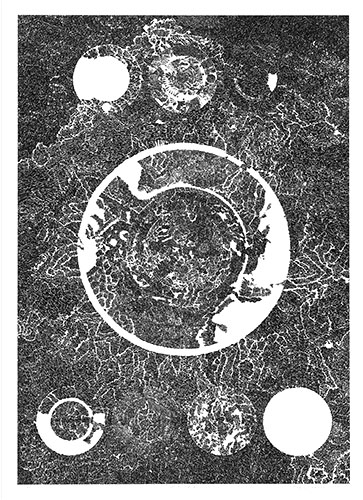

The mandala drawings (1963-71) do something similar through different means. Echoing forms seen in religious art from many traditions, these dizzying topographies of interlinked marks connect in the manner of highly skewed labyrinths. They’re executed as allover drawings. To look at them is to become lost in microscopic lines that form islands of positive and negative space. With no beginning and no end, they visualize infinity, making clear that infinity can’t be physically grasped, only grappled with. Thus, the question arises: how did Conner make these drawings? Drugs? Conner said his experiments were influential, but he never worked while high; he said it was impossible. So how, then, did he summon the superhuman concentration required? Evidence points back to his films. The image density and the rhythms correspond to the modulations of lightness and darkness seen in the mandalas. And while drawing and filmmaking are indisputably worlds apart, Conner’s handling of them is of a piece conceptually — a point the ICA would have done well to make by screening one or two of them in the space it typically reserves for that purpose. As it stands, the mandala drawings, any one of which merit extended contemplation, are more than enough. Several dozen are on view and they occupy about a quarter of the available wall space — more if you count those that appear in the collaborative works made with McClure, those Conner converted to slides for light shows, and those he worked into his engraving collages.

|

.jpg) |

Conner defied conventions in many other ways. After being invited to make lithographs at the Tamarind Institute in 1965, he refuse to sign them, insisting instead on applying an inky thumbprint. That violated not only established protocols, but cast aspersions on the technical capabilities of the press. It also, intentionally or not, forecast the epidemic of forgery that would rock the museum world in subsequent decades. In so doing he made a point: that while an artist’s signature can be forged, his fingerprints cannot, thereby accruing value to a thumbprint. Having done that, he later resisted being fingerprinted for a teaching job at San Jose State, arguing, in 1974, that to submit would be tantamount to allowing a confiscation of his art without pay. (A compromise was eventually reached in which the artist agreed to create an editioned set of prints, one of which is displayed.) There were also elaborate pranks, like his mock run for supervisor in San Francisco during which he recited Biblical passages in a televised debate. Evidence of these provocations is well documented in Somebody Else’s Prints.

|

Bruce Conner lived on the fringes of society and was only bound by his integrity as a thinker artist who could reach outside the bounds of what he knew already as an artist. Most artists never leave their comfort zone but he adapted into forms as though a spirit moving in and around ideas and outside of conventional norms. His adaptatation allow for some of the most insightful and original artwork to come out of his era as a painter,assemblagist,sculpture, collaging,lithographer and film maker. A Master to be recognized