|

“Alive as you or me.” The lyric comes from the union anthem Joe Hill, and though its subject is literally a continent removed from the Holocaust, those words reverberated in my mind as I watched Péter Forgács’ Letters to Afar, a video installation culled from home movies made in the interwar years by Polish-American immigrants visiting their overseas relatives. The song, as those of certain age will recall, tells of a visitation dream in which an organizer, long dead, appears as a palpable visage.

|

.jpg) |

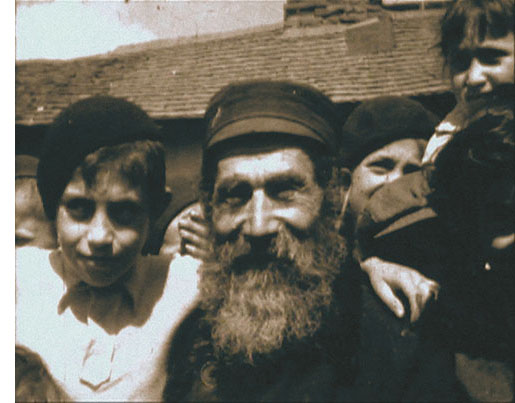

privation rules. Open-air markets, government buildings, shops, rundown apartments, streets and synagogues – the stuff of shtetl life – form the backdrop to this activity in locales across Poland. In one notable instance, in a film shot by a travel agent, Gustav Eisner, whose specialty was organizing old country tours, family members who hadn’t seen each other in years, hug, kiss, cajole, dance and rejoice — reuniting for what we sense may be the last time. Most of the Americans arrived as tourists, but in many cases, they also represented landmanshafts, stateside aid societies formed to help the communities from which they immigrated.

|

In other sections of this superbly installed, immersive exhibit, Forgács projects images onto multiple layers of scrim suspended at monumental scale from the ceiling. In these we see some of the same people shown in the multi-part montages. Only here they appear more vaporous, more shadow-like, more resistant to our efforts to bring them into focus. In this format they communicate the impending nightmare in a way that the montages don’t; and in the manner of religious art, which mixes beauty and suffering, they convey, in almost mystical terms, the enormity of the crimes — wrapping the victims in a haze that replicates the fog of memory. The result is a spectacle that is both alluring and horrifying. As such, this portion of the show compels us to reflect even more deeply on the events of the past century, and, by extension, on the Holocausts taking place today. The exhibition's triumph, in the end, rests with how it visually reframes the existential question has vexed mankind since the end of WWII: how to process events that defy reason?