|

|

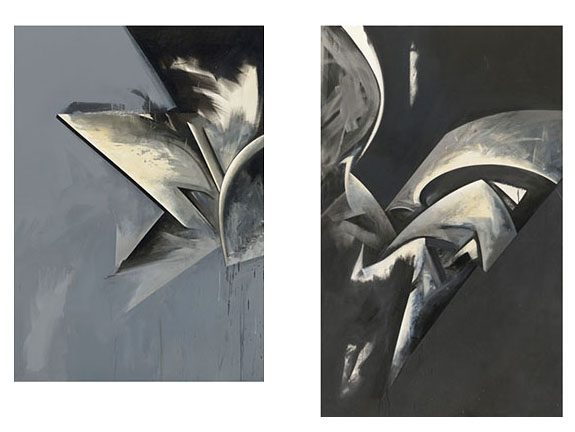

Artists today achieve this kind of otherness by different means: Photoshop, 3-D printers, animation, augmented reality and, I suspect, even more exotic apps that have yet to go mainstream. The effects generated are markedly different than DeFeo’s owing to the technologies involved. But the links, at least conceptually, between DeFeo’s methods and those of pioneering digital painters like Amy Ellingson are clear. She, like DeFeo, tears apart and reassembles preexisting forms to create category-defying hybrids that seem capable of endless permutation. At a technologically less sophisticated level, it’s tempting to draw analogies between DeFeo and William Burroughs, the Beat-era author who constructed his most famous books with a cut-and-paste process similar to DeFeo's, recycling themes and entire tracts of previously published verbiage in new editions of his books. And while there’s no evidence that she read or was influenced by Burroughs, we know for certain that he was a towering influence on many of DeFeo’s Beat-era cohorts. Which is to say, there’s a strong likelihood that talk of his methods ran as thick as wine at the soirees she and her husband, the painter Wally Hedrick, held at their Fillmore Street apartment.

|

.jpg) |

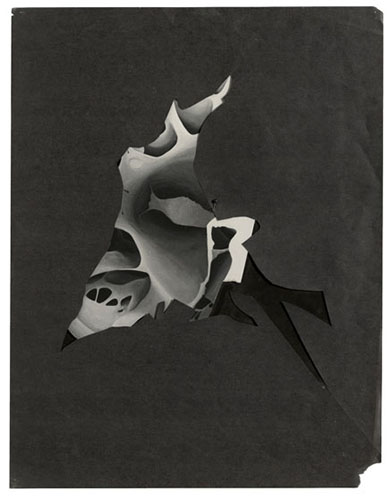

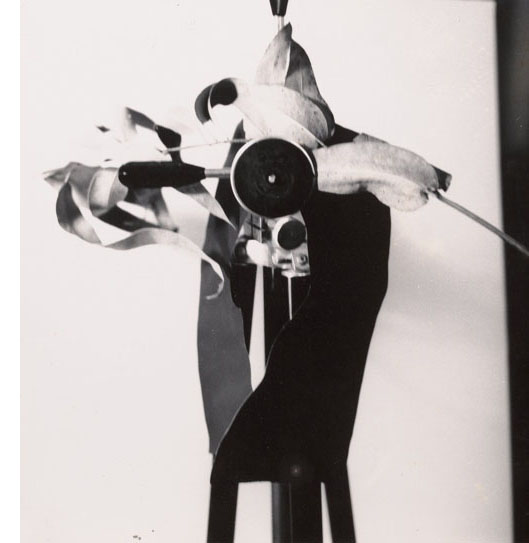

appear to be the source for these collages, and in each, the pieces are arrayed differently and reproduced by different means: camera, photocopier and by hand. The most powerful of the three is a gelatin silver print. It’s sliced away from its background and mounted on black paper. The collage itself — a mélange of anthropomorphic features (kicking legs, wings, a body and a bird beak) connect via a network of nooks and crannies resembling a wind-carved rock. The feel is Dadaesque; the range of tonal values, set off by the contrasting background, makes it hard to know whether you’re looking at a straight photo or a relief sculpture.

|