|

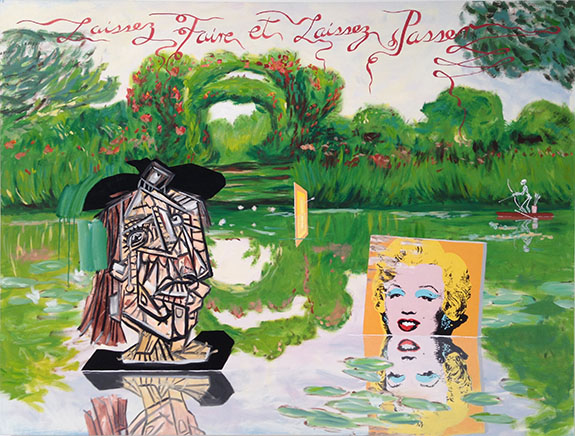

The history of art is a history of appropriation. Yet the term did not enter art parlance until the contemporary era. In the late 20th century, appropriation gained currency as a keyword describing strategies adopted by artists from Andy Warhol to Sherrie Levine who repurposed existing artworks and images. So-called appropriation art engages with systems of cultural value unwritten by such concepts as originality, authenticity and iconicity. Earlier, at the turn of the 20th century, “primitivists” (from Paul Gauguin to Pablo Picasso) made the cultural appropriations underpinning European modernism. Colonialist booty from Africa, Oceana, and the Americas stored in European museums inspired artworks by expressionists, fauvists, cubists and surrealists.

|

|

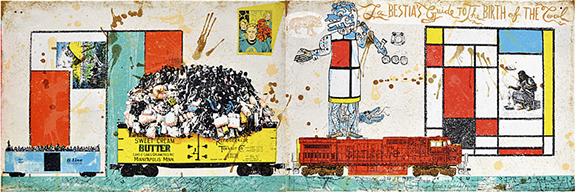

Several such works are on view. They include, in addition to Mindful Savage’s Guide to Reverse Modernism, La Bestia’s Guide to the Birth of Cool (on handmade amate paper), Canibales Daguerrotipicos (digital prints), and Illegal Alien’s Guide to Mindfulness (acrylic on rust patinated steel). With these compound pieces, Chagoya demonstrates his virtuosity in a range of techniques that include, in addition to painting, lithography, copperplate etching, woodcut, letterpress, collage, calligraphy, and digitally manipulated photographs. He recasts a wide variety of iconic images (Edward Curtis photographs of “vanishing” tribes, Yves St. Laurent fashion plates, ethnographic illustrations, political cartoons, comic book super heroes, Posada engravings, Mondrian paintings, Nike and Apple logos, Toltec masks, Day of the Dead skeletons, Catholic saints) to unsettle triumphal narratives of European and Euro-American hegemony. Chagoya acknowledges history as “an ideological construction made by those who win wars,” and his codices make the case that wars are never won once and for all. For every history written by the winners there are others waiting to be written by the vanquished, poised to re-emerge transformed in unpredictable ways.

2015.jpg) |

the final frame of Canibales Daguerrotipicos, atop the hybrid body of a Mexican giant and a revolutionary, suggests that the process is not orderly, linear or unidirectional.

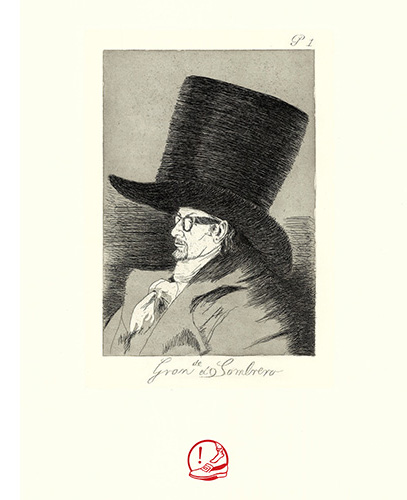

The exhibit contains works of various formats that differently harness the critical potential of appropriation. His Recurrent Goya etchings, for example, ally themselves with the 18th-century Spanish master’s Caprichos (caprices) and Disparates/Proverbios (follies/proverbs). Chagoya keeps faith with Goya’s technique and compositions, but updates the iconography to comment satirically on contemporary issues. These resonate with Goya’s Inquisition-era preoccupations: corruption in the Catholic church, abuse of political power, economic disparity, institutionalized violence, the ravages of war.

|

Terrific piece. I’m appropriating it for my teaching in all classes – Latin American, Modern, and Contemporary. Hope to get to the show.