by David M. Roth

If you think Pop Surrealism concerns itself only with big-eyed females engaged in psycho-sexual/sci-fi escapades, a new show commemorating the first ten years of Hi-Fructose magazine will substantially enlarge your understanding and appreciation of this oft-maligned subgenre. Organized by Alison Byrne and Heather Hakimzadeh of the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, Turn the Page features works from 51 artists chosen from more than 300 that have appeared in the San Francisco-based magazine since its 2005 inception.

That entry date made the magazine a relative latecomer. Its competitors, the more street-oriented Juxtapoz, and the Asian-themed pop culture ‘zine, Giant Robot, both launched in 1994. Still, Hi-Fructose, with a combined print and online audience “in the hundreds of thousands,” has done much nurture Pop Surrealism and its many offshoots. The goal, according to its founders — Annie Owens, a pop surrealist watercolorist, and Daniel “Attaboy”

The work on view is mostly figurative, inspired by comics, TV cartoons, science fiction, Disney, gothic horror, graphic novels, manga, Kawaii, craft, mythology and big swaths of art history. It conveys social, political, religious and environmental themes, whacked-out fantasies and autobiographical confession, the latter poignantly expressed by Beth Cavener in two sculptures in which a fox and rabbit portray the all-too-human pain of a bad marriage and an unwanted pregnancy. The first, Trapped, shows a snared fox chewing off a leg to rid itself of a wedding

Anthropomorphic fusions of this sort abound in Pop Surrealism, often accompanied by doe-eyed waifs of the kind Margaret Keane painted in the 1950s and 1960s. Though they were about as fashionable in fine art circles as Thomas Kincaid, pop surrealists over the years have appropriated them repeatedly, occasionally to powerful effect. Mark Ryden is one of them. His wide-eye, pale-skinned, platinum-haired girls – oftentimes surrounded by slabs of raw meat — have become universal signposts of debauched innocence. Executed in a seamless mash-up of late-Victorian styles, his paintings combine barbed critiques of Catholicism with ambiguous references to Abraham Lincoln, whose visage (along with that of Barbie) in Rosie’s Tea Party (No. 56) suggests unsavory links between state, religion and childhood indoctrination. Using his daughter as a model for the series, the artist makes literal the idea of transubstantiation: Rosie saws a ham hock emblazoned with the words “Mystici Corporus Cristi.” In a show filled

with provocations, this one’s clearly the sharpest. Jennybird Alcantara, calling more on Betty Boop than on Keane, employs big eyes to depict the opposite: a state of prelapsarian harmony in Creatures of Saintly Disguise. This nod to Edward Hicks’ 19th century series The Peaceable Kingdom shows a bear, a tiger and a serpent entwining a multi-legged girl, ringed at the hips by a floating forest and pierced through the palm by a dandelion. It inflicts a bloodless stigmata.

While you can draw thematic and stylistic parallels between select pieces such as these, the show has little cohesion. By design, Hi-Fructose is all over the map, and so, at every turn, is Turn the Page. Thus, the discord you sense in the opening gallery mirrors the overall character of the exhibition, beginning with Todd Schorr’s monster-filled tableau, The Last Expedition of Commander Peary. Situated directly opposite Alcantara’s painting, it shows the explorer taking an icepick to King Kong, an indictment not so much of the movie character, as of the perils of

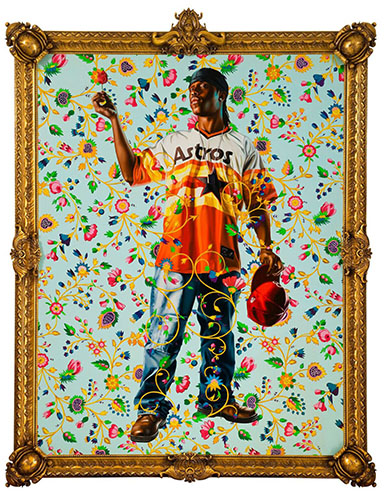

Yet for all the zaniness on display, bona fide treasures of a less sensational variety are everywhere to be found. One of them is the exhibition’s literal centerpiece, Wim Delvoye’s gleaming Cement Truck. The artist used laser-cut stainless steel to painstakingly re-create the intricate patterning of gothic architecture, out of which he built a large-scale model of a cement mixer suspended between church steeples. The metaphor, of faith spun into a formless slurry, may be a tad obvious, but it packs a rock-solid conceptual punch, much like the churches and temples Al Farrow makes from bullet casings, linking religion and war, that the Crocker put on view in 2015. Lisa Nilsson’s sculpture, Female Thorax, like Delvoye’s Cement Truck, is also an exercise in craft, but the precision with which the artist renders an anatomical crossection out of rolled bits of colored paper makes for an object of stunning abstract beauty. It’s tucked into a dark corner, so you could easily miss it. Kris Kuksi’s Eros at Play, a wall-mounted sculpture built from toy soldiers, has no detectable erotic content, but it’s definitely a comment on war, consisting mainly of figures arrayed in tiers to convey the look a battle waged on steep terrain among combatants from different eras and nationalities. And, as much as I chafe at the “royalty” designation Kehinde Wiley applies to his

# # #

“Turn the Page: The First Ten years of Hi-Fructose” @ Crocker Art Museum through September 17, 2017.

About the author:

David M. Roth is the editor and publisher of Squarecylinder.