by Mark Van Proyen

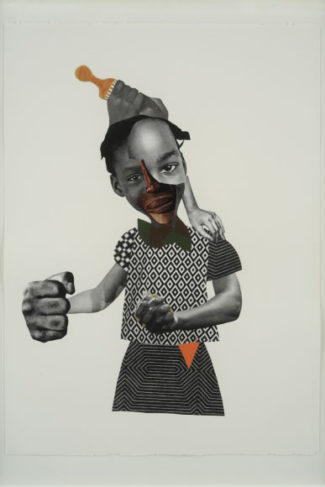

The hopes, frustrations and perilous potentials of African-American girlhood provide the subject matter for Deborah Roberts’ new series of 14 collages. The four largest are about 44 inches tall and feature singular, full-figure representations of young girls in the seven-to-nine year age group, all surrounded by large expanses of clean white paper. Other works, at 30 X 22 inches, reveal only three-quarter figure representations of similar young females. Each simultaneously embraces and steps away from most of the well-known examples of the African-American collage tradition as practiced by the likes of Romare Beardon and updated by Mickalene Thomas, among many others.

Whereas the work of those prior artists makes a point of placing their figurative protagonists in complex, highly narrativized environments, Roberts purposefully separates her figures from any indication of context save that which might be inferred from their flamboyant dress, ungainly body language and ambivalent facial expressions. All of these aspects come together to force the viewer to take note of what is truly salient about them, that being their affecting call for the viewer to exercise a particular kind of empathy toward the cobbled-together identities of young persons who, through no fault of their own, are represented in a state of uncomfortable isolation, with all of its potential peril.

Someone more cynical than myself might be tempted to see these works as a conflation of the Black Lives Matter and the #MeToo movements, parading under the timely banner of Black History month. Such an opinion could only be forgiven if its bearer had not actually seen Roberts’ exhibition, as its seductive call to empathy abolishes such cynicism. In terms of the themes and material manifestations of these works, we see indications of identities that have been fractured or otherwise disrupted and then put back together from available materials and given new purpose, ergo the title of the exhibition Uninterupted, which speaks of the reversal of a moment of shattering trauma.

Each of these works gives the viewer a lot to see. At first glance, it looks as if Roberts is

The faces that we see in these works are miniature emotional kaleidoscopes, running a full gamut from happy confidence to crippling self-doubt. They often seem too large for the bodies upon which they are perched. Certain bisected portions regard the viewer from a frontal position, while other parts peek out from a profile view. Some portions are in grainy color, while others are subtly mid-toned so as to defeat stark binaries between white and black, implicitly casting the subjects in the interstitial space between those two poles. In all cases, they enact the kind of undoing of indifference that writers such as Emmanuel Levinas and Judith Butler called for in their respective critiques of the ethics of rationalized exploitation.

|

|

And so, a question: at whom are these girls looking at with such complex attitudes? Or, to use more precise artspeak: who is the implied narratee being addressed by these narrations of vulnerable and presumably impressionable girlhood? If we answer that Roberts’ works are directed at the generic, implicitly white and affluent artworld viewer, we get one answer, in that such viewers tend to not see the African-American experience with much clarity. Meaning, these works can be read as attempts to rectify that situation. Fair enough. But that is just the outer layer of what is going on here. Another layer has the girls looking at themselves in a mirror of self-interrogation, while a related layer might pertain to the cultural mythos of the absent African American father; meaning, these girls can be seen as seeking paternal

# # #

Deborah Roberts: “Uninterrupted” @ Jenkins Johnson Gallery through March 17, 2018.

Images: Copyright Deborah Roberts, courtesy Jenkins Johnson gallery.

About the Author:

Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries focus on satirizing the tragic consequences of blind faith placed in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include: Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak's December 9, 2014 interview, published on Broke Ass Stuart's Goddamn Website.