by David M. Roth

Her current series, Deviance: Women in the Asylum During the Fascist Regime, employs a similar modus operandi. It’s based on a trove of photos and documents that were exhibited at the Rome Area History Museum under the same title, prefixed with the words Flowers of Evil. Lundy saw the show in 2016 during a six-week artist residency at the American Academy. Her stay subsequently stretched to a year after one of the exhibition’s organizers, Annacarla Valeriano, of the University of Teramo, offered to help her examine the archives of the Sant’Antonio Abate asylum, the psychiatric hospital from which the source photos for this series, made during 20 years of fascist rule (1920 to 1943), were culled. The paintings add a fresh chapter to the artist’s ongoing examination of the dark corners of women’s history.

What justified the incarceration of these innocent women and their barbaric treatment, which included, among many things, the withholding of basic necessities? The most common reason listed on medical records was a condition called “female deviance.” It had nothing to do with mental illness. Records reveal behavioral descriptions such as talkative, unstable, inconsistent,

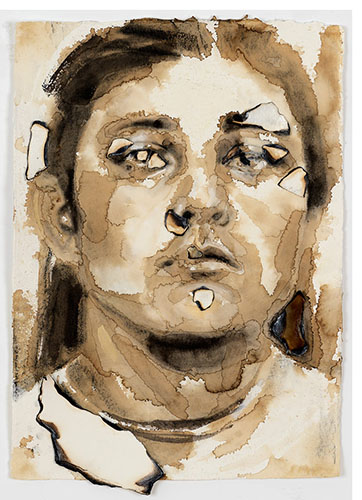

Viewers familiar with Lundy’s work will note striking differences between these paintings and those that came before. Where the surfaces of her portraits of prostitutes consisted of thick accretions of acrylic paint and cinders that resembled geological events coaxed into corporeal form, her Italian asylum paintings, while employing many of the same materials and methods (coffee, ink, mica and selective burning of paper), exhibit none of the former series’ topographic qualities. Lundy continues to build up thick surfaces, but she now scrapes them to near-flatness. Up close, the portraits have the look of pieced-together forensic evidence, the main elements being blotchy stains and burned segments set against yawning tracts of white space. Their fractured, almost apparitional appearance mirrors the photographic process, of forms and shadows emerging from chemical baths that were fouled during development, leaving some information intact, some lost.

Consequently, it’s difficult to establish a sense of who these women really were. We see their identifying physical features clearly enough, but from them all we can do is speculate, noting the expressions they wore at the moment they were captured. And while hairstyles, clothing and skin color do give some indication about where, on the social ladder, these women stood before they were forcibly removed from society, their identities and their emotional lives remain

Here it’s worth noting that Lundy earned her MFA at Mills College and studied with Hung Liu, the Chinese-American painter, who, for decades, has worked from historic photos with the intent of “summoning ghosts.” By dint of the subjects’ surroundings, her paintings offer a lot of social and historical commentary – particularly for viewers versed in 19th and 20th century Chinese history.

For Lundy, who spent her childhood living in a Saudi Arabia, women’s issues have long loomed large. Early on she sensed that the women she lived among were treated as inferiors, held separate and hidden from society. Even as a foreigner, she often experienced these limitations and judgments. As a young girl she also felt the sting of sexual harassment. After that experience, pivoting her attention towards prisoners, prostitutes and patients seemed natural, maybe inevitable.

The relevance of this work seems obvious, and not just for women in underdeveloped

Our government has already jailed the children of innocent asylum seekers, slow-walked court orders to free them, and scared away countless others from exercising constitutionally protected rights. Meanwhile, chants of “Lock her up!” still resound at Trump rallies. What’s next?

# # #

Deviance: Women in the Asylum During the Fascist Regime @ Nancy Toomey Fine Art, through October 13, 2018. Artist Reception: September 8, 5-7 pm.

About the author:

David M. Roth is the editor and publisher of Squarecylinder.