by Patricia Albers

Plato compared memory to markings on a wax tablet. Saint Augustine likened it to storehouses and treasure chambers filled with sights, sounds and smells. One 19th-century commentator described the then-new medium of photography as “a mirror with a memory.” Today, neurologists are digitally simulating the brain, RAM is for sale at Best Buy, and the going analogy for memory is the computer. Encode/Store/Retrieve, on view at the San José Museum of Art through April 21, invites viewers to keep that metaphor in mind as they contemplate some 30 works of art from the museum’s permanent collection. It’s a timely and ambitious exhibition.

Elias Sime’s Tightrope: Behind the Processor #5 (2023), hanging in the museum’s stairwell, is the exemplar. Based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Sime searches out discarded electronic components at the city’s street markets. In the quilt-like Tightrope, he coils and intertwines computer wires, organizes them into colorful grids, and frames them with obsolete circuit boards. His work evokes the human brain, with its wrinkles and folds, complex neural networks, and modular structure. Indeed, this very hardware once served to encode, store, and retrieve data, albeit in ways now seen as crude. Viewed from one perspective, Tightrope alludes to African weaving, braiding, and reuse traditions. From another, it recalls the Global North’s command of systems of data collection and transmission, the detritus of which ends up in the South.

One flight up from Tightrope, viewers enter the galleries, organized by the categories named in the title. The first, Encode, groups several works steeped in cultural memories. In Ancestral Altar #12 (2005), Binh Danh relies on the chlorophyll print, a hybrid medium he invented. Three mug shots of prisoners, reproduced using photosynthesis, appear ghost-like on a tropical leaf, along with a flight of butterflies. Identified only by the prison codes on tags hanging from their necks, the prisoners were among some 20,000 Cambodians locked up, tortured, documented and then murdered by the Khmer Rouge. In Ancestral Altar # 12, Danh draws on the most local and ephemeral of materials—a leaf, butterfly specimens and processes—a plant reacting to sunlight—to express his subjects’ loss and memorialize them.

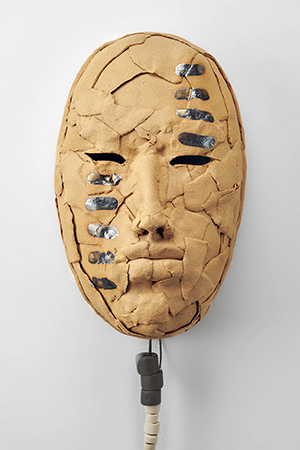

For the Native American artist Rose B. Simpson, cultural memory abides in clay. Heir to a seven-century Santa Clara Pueblo and family ceramic tradition, Simpson manifests a bone-bred bond with her medium in the mask-like Sun I (2019). This enigmatic presence comprises overlapping cardboard-thin scraps of clay. Columnar black strokes on the forehead and cheeks align with its slit eyes and mouth, visually stitching the face together, as if it were emerging from a remembered past self.

Simpson’s haptic Sun I hangs across from Jim Campbell’s high-tech portraits of his parents. Photograph of My Mother (1996) centers on a snapshot of a carefree-looking woman encased in layered glass. From there, wires dangle to an aluminum box mounted on the wall. Labeled “My Breath January 1996 1 hour,” it emits the sound of the artist breathing. With each exhalation, the glass over the snapshot fogs up, graying his mother’s image. With each inhalation, it clears. Thus, Campbell conjoins glimpses of his mother as she once was with that most primal of physiological functions. Counterintuitively, he entrusts deeply subjective memories to electronic hardware. As in poetry, much is elided.

The next gallery, Store, highlights art that speaks of how societies cache vital knowledge. Enrique Chagoya’s The Labyrinth of Liberty (2004), a painting on amate (a type of bark), reinvents the pre-Columbian codex, inscribed with pictographs and texts that record the past and guide the future. Darlene Nguyen-Ely’s mixed media The Shrine XII (1993) takes inspiration from one of the religious icons the artist remembers from her childhood in Vietnam. Xiaoze Xie’s photogravures on paper, titled Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto (2007), pull in close to the spines of ancient books. They are degraded survivors, for now, of the vicissitudes of history and the passage of time. But not all repositories of collective memory fare so well. Vast numbers of codices perished at the hands of the conquistadores; vast numbers of shrines met destruction in the Vietnam War.

With Val Britton’s The Sea Within (2004), in that same gallery, representational art yields to abstraction and small scale to large. Using graphite, ink and collage on paper, Britton has layered map-like forms with blotches and splatters of ink and delicate linear circuits. Scale is indeterminate. The Sea Within evokes a world that is simultaneously psychological, terrestrial and cosmic. The mind’s dynamic plasticity, Britton’s piece suggests, makes it a microcosm of a universe in a perpetual state of becoming.

Turning from Store to Retrieve, the exhibition addresses ways in which people bring memories to conscious attention. Filling one corner of the gallery, Stephanie Syjuco’s International Orange Commemorative Store (A Proposition) (2012) proves the idea of mass-market souvenirs as a means of keeping the past alive. Commissioned for the 75th anniversary celebration of the Golden Gate Bridge, her installation mimics a standard tourist gift shop, except that the merchandise lacks logos and price tags. Everything is international orange, the color of the Golden Gate Bridge, yet it conjures little of the lived experience of a visit to the iconic span.

mixed media installation

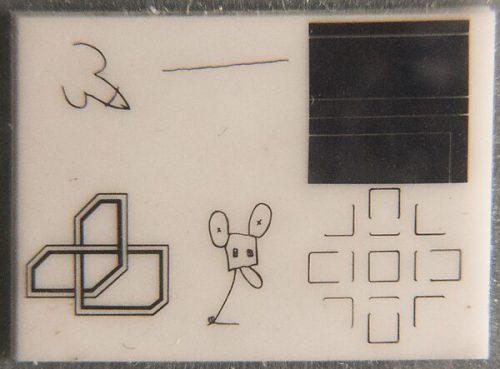

As tiny as Syjuco’s work is big, Forrest Myers’ Moon Museum (1969) combines doodles by himself and five other American artists: Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, John Chamberlain and David Novros. Warhol turned his initials into a crude phallus that doubles as a rocket ship. Claes Oldenburg sketched an odd Mickey Mouse. Myers contributed a drawing of interlocking geometric shapes. Rauschenberg drew a single line, while Chamberlain and Novros made sketches based on circutry. Myers lithographed all of them onto a thumbnail-size ceramic wafer. Reportedly attached to the Apollo 12 spacecraft, Moon Museum is believed to be the first work of art to travel to the moon, asserting both the American presence on the lunar surface and the existence of the six artist Kilroys.

Literally and metaphorically, Steven Deo’s mixed media Trailways Baggage (2003) brings memory down to earth. The artist compacted hundreds of battered leather shoe parts into three suitcases and a guitar case. These clutter a low platform, along with a crushed coffee cup, a couple of cigarette butts and several pairs of intact footwear. Viewed through the lens of the exhibition’s theme, Trailways Baggage evokes memory fragments, coalescing yet clouded. A seedy bus station. Overpacked bags. The odor of cigarette smoke. The taste of stale coffee.

As much as any work in the exhibition, Trailways Baggage prompts musings about both the richness of the theme of memory and the inadequacy of the Encode/Store/Retrieve analogy. Our digital devices input, process, store, and spit out data with flawless consistency. Our brains, however, don’t work that way. Human memories are intertwined and unsystematic. They answer to sensory cues. They mingle experience with imagination. Their content and meanings are constantly changing. There is no human hard drive.

The realms of human memory are analog, acknowledges the curator, Juan Omar Rodriguez, in a wall text. Reaching for a metaphor that invites multiplicitous readings of the art, he writes of a “memory ecosystem” that crosses “biological, geological, cultural, and institutional” lines.

One of the last works in the exhibition, Inez Storer’s Histories (1996), underscores Rodriguez’s words. This autobiographical oil and collage piece centers on a kneeling and blindfolded figure. Images float around her: an elaborate place setting, a patch of flowered wallpaper, an old clipping of an actress, a menorah. An easel holds a painting in which a second figure appears. From there, a red liquid drips onto the hand of the central figure, extended to catch it and perhaps also to pray.

Histories is moored by two episodes in Storer’s life. As a Catholic teenager, the artist was stunned when her use of a Yiddish accent at a family dinner so upset her German-born mother that she fled the room. In response to questioning, her father confirmed Storer’s suspicion that her mother was Jewish. Yet he admonished his daughter never to speak of it. Only when Storer was in her sixties and her mother was dying did the artist learn of her escape from the Holocaust and of the existence of an extended family.

“A home as unwieldy as its picture,” writes Storer, implying the difficulties of putting recollections into tangible form. Indeed, Histories never quite coheres into narrative. Not unlike the human brain, it gathers images from disparate times and places and perhaps with varying degrees of reality. So, too, the human brain functions. The memories that thicket our minds—and the art we make to represent them—obey no binary logic.

# # #

“Encode/Store/Retrieve” @ San José Museum of Art through April 21, 2024. The exhibition also includes works by Wallace Berman, Chryssa, Bruce Hasson, Xandra Ibarra, Darlene Nguyen-Ely, Margaret Nielsen, Harold Paris, Beverly Rayner, Analia Saban and Katherine Sherwood.

About the author: Patricia Albers is a Bay Area writer, art historian, and editor. Her books include “Joan Mitchell, Lady Painter: A Life” and “Shadows, Fire, Snow: The Life of Tina Modotti.” Her biography of photographer André Kertész is forthcoming from Other Press.