by Mark Van Proyen

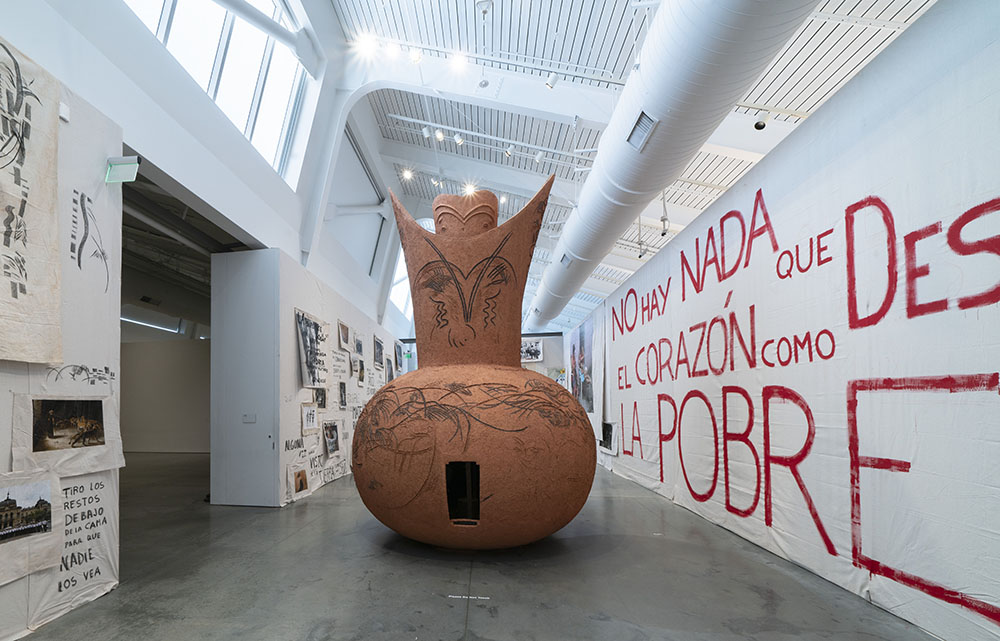

When translated into English, No Hay Nada Que Destruya El Corazón Como La Pobreza means Nothing Destroys the Heart Like Poverty. It is the title of Gabriel Chaile’s first museum exhibition in the United States, manifested here as a singular installation of multiple components. Central among them is a 14-foot-tall ceramic vessel that looks large enough to be an oven, with an open back door allowing curious viewers to peer inside to discover details of its construction. The un-fired and un-glazed vessel is made of red clay applied to a wooden superstructure. Most certainly, it is not sturdy enough to be transported, meaning it is an impermanent feature of a temporary installation. The shape of the stout object is unusual and subtly anthropomorphic, looking like it is about to break out into an animated dance. It alludes to a neolithic goddess figure with a sneering face looking down on the viewer from above. On all sides, its surface is scored and adorned with abstract design elements echoing neolithic representations of lightning.

The exhibition literature states that Chaile is from the region of northwestern Argentina called Tucumán, once occupied by the pre-colonial Condorhuasi-Alamito people (400 BCE to CE 700), who flourished before being absorbed into the southern frontier of the Inca empire. Given this brief, we can presume that Chaile is paying homage to the distinctive ceramic traditions of those ancestors, bringing them to gargantuan life to suggest an uncanny, semi-surrealistic reanimation. His presentation of similar ceramic forms at the 2022 Venice Biennial elicited similar observations because Surrealism was the theme of that exhibition. Chaile’s form might also be read as a salute to Peter Voulkos, who taught at UC Berkeley for many years and pioneered the California Clay Movement. Too much of a stretch? Okay, but it does lead to

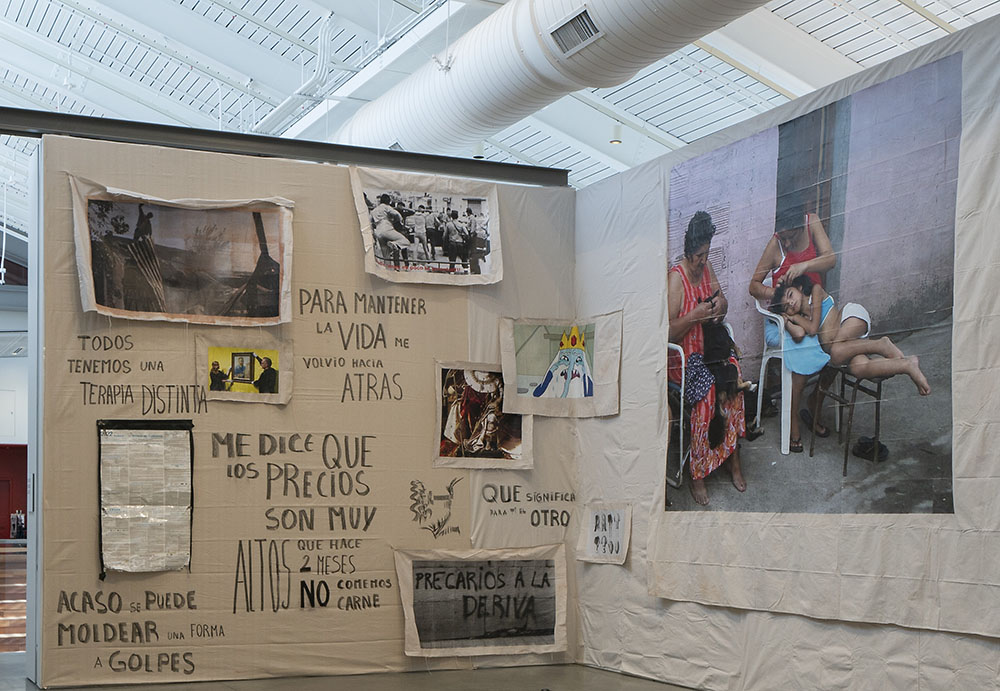

another aspect of Chaile’s installation, that being its chaotic documentation of popular struggles against the Argentinian government’s mismanagement of national resources and its repression of Indigenous peoples. Here, the connection to Berkeley is firmer because that city is well-known for its long history of grassroots political activism.

The walls surrounding the vessel are covered with several layers of unprimed canvas that overlap one another like irregularly placed shingles. Many carry photographs that reflect aspects of life in Argentina. These images vary in size, the largest being an affecting image of a grandmother, mother and daughter sharing a moment where the youngest member of the trio looks back at the camera suspiciously. Others, like an image of an antique government building, are small. Swaths of unprimed canvas emblazoned by political slogans written in charcoal complement the array of photographs. All are written in Spanish and often idiomatic, which might perplex English-only speakers. Phrases such as Que Significa Para Ti El Otra (What Does the Other Mean to You) or Precarios A La Deriva (Precarious Drift) are not as tendentious as most political slogans, but they do signal the despair of life in a country with 200 percent inflation. (Translations are supplied on plastic cards near the gallery entrance.)

How might we understand the relationship between the giant ceramic vessel, the photos and the syncopated signage? Answers to this question are not easy because they require imagination on the part of the viewer. My take is that they speak of the lingering effects of colonization, which continues to make life almost unbearable for an indigenous population that has no choice but to depend on a dysfunctional and indifferent government. In contradiction to the despair signaled by written components, the centerpiece of the exhibition can be read as a spirit form that wards off those feelings by refocusing attention on an ancestral form that conveys strength and resilient purpose to the victims of self-righteous “history.”

How might we understand the relationship between the giant ceramic vessel, the photos and the syncopated signage? Answers to this question are not easy because they require imagination on the part of the viewer. My take is that they speak of the lingering effects of colonization, which continues to make life almost unbearable for an indigenous population that has no choice but to depend on a dysfunctional and indifferent government. In contradiction to the despair signaled by written components, the centerpiece of the exhibition can be read as a spirit form that wards off those feelings by refocusing attention on an ancestral form that conveys strength and resilient purpose to the victims of self-righteous “history.”

# # #

MATRIX 283/Gabriel Chaile: No Hay Nada Que Destruya El Corazón Como La Pobreza @ Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) through April 14, 2024.

About the author: Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries emphasize the tragic consequences of blind faith in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak’s interview on Broke-Ass Stuart’s website.

Photos: Whit Forrester

MVP is a major dude.