by Renny Pritikin

There’s an intriguing photograph early in the Bonnie Ora Sherk retrospective, Life Frames Since 1970. It was taken at the Newport Harbor Museum in 1972, showing Sherk alongside other San Francisco artists Paul Kos, Howard Fried, Tom Marioni and Terry Fox. They’re all impossibly young, sporting a lot of hair, smiling shyly as though acknowledging how lucky they were to be at the center of a movement changing our conception of art. Though their practices were different and would grow further apart, at this early stage, their ideas revolved around the same breakthrough set of insights: a refusal to accept art’s elevated status separate from everyday life, a further refusal to accept boundaries among art forms, especially between visual art and performing arts and a willingness to employ humor as an art medium. Because so much of their work had no audience, cameras were essential to record these performances and give them ongoing life. Several of these events can be understood as viral memes before there was a name for such things.

I’m thinking particularly of Sherk’s breakthrough action Public Lunch (1971), one of several that took place at the San Francisco Zoo. It appeals to me that it took place in a public space and was deeply entwined with quotidian life, stumbled upon unintentionally by the public. Sherk ate an elegant meal on a white-linen-covered table in the Lion House, seated in an empty cage between two tigers being fed slabs of raw meat. Sherk hijacked the structure of traditional proscenium theater: she was on an elevated stage, illuminated, facing an audience, reinventing a “found” art form—the stage—and a “found” display system—the zoo—to critique both. She lounged around, wrote, and killed time, dressed in an elegant black velvet gown. It marked the beginning of Sherk’s career-long interest in exploring human chauvinism toward animals and nature. Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle had been published only four years earlier, examining how public fascination with sensational large-scale events could serve the political ends of ruling elites. Sherk’s zoo works served as both a parody of and an homage to Debord. However, Public Lunch must be read above all as a feminist text, demonstrating how women — then and now — were so often on display and kept as virtual pets, restrained, reduced, and prettified. A white rat sat in an enclosure on the table beside the artist, a cage in a cage in a cage.

Sherk (1945-2021) was not alone in such endeavors. Howard Fried and Paul Kos, Sherk’s Bay Area colleagues, made memorable audience-free events around the same time that also live on through film and video documentation. The political and poetic context of Sherk’s performative work echoes in Fried’s film The Burghers of Fort Worth (1975), in which he hired professional coaches to advise him about his golf swing on a Texas course, their running commentary gently revealing essential characteristics of America’s regional and generational conflicts. While Sherk became known for exploring nature in an urban context, Kos reveled in the magical possibilities he discovered living part-time in the Sierra wilderness. In Ice Makes Fire (1974), he videotaped himself fashioning a lens out of ice, which he used to focus the sun’s rays, setting a campfire ablaze.

Sherk’s series of late 1970 performances, Sitting Still I-XII, are as odd and striking today as they were half a century ago. They all took place for one hour in public spaces where the people encountering the seated artist staring into space might not notice or choose to ignore her at, say, a corner in the financial district, on the Golden Gate Bridge walkway, or most powerfully, in a flooded urban industrial wasteland. In the latter, Sitting Still I, Sherk appears in a strapless gown, coiffed, seated in a stuffed chair, elegantly holding a cigarette above her bent elbow, lost in thought. Surrounded by an acre of shallow water, she could be a movie actress waiting to be called on set, a scene reminiscent of Cindy Sherman’s self-portraits a decade later. One thinks of nature photographers who capture a forest reflected in a lake, forming an upside-down homage to nature’s perfection. Sherk’s absurdist photograph reiterates the context of her act, as the water reflects not trees but urban detritus: lamp posts, abandoned tires, and a lonely tricycle up to its hubs in liquid. Sherk is as abandoned and isolated as the junk stuck in the mud. We witness the artist creating an art form — performance — with attributes that include her body, without text or narrative, with a measure of risk, extending the sculpture’s three dimensions to include the notion of time.

Organized chronologically by Tanya Zimbardo, Life Frames reveals how Sherk’s creative output in these early years unfolded quickly, one idea after another. (Except for artist books, the exhibition consists almost entirely of documentation and project proposals because, as a social practice artist, Sherk left behind few art objects). During that same period, she grasped the theme of what would become her life’s work: strategies for accommodating the natural world within the urban settings, seen initially in the Portable Parks series, executed in collaboration with Howard Levine.

In these, Sherk temporarily installed sod, picnic furniture, potted palm, and sometimes animals in unlikely areas of San Francisco. One black-and-white photo documents a row of palms, their crowns poking above the ramparts of the now-demolished freeway overpass on Market Street like hand puppets. A grassed-over block of Maiden Lane had penned llama available for petting. Another iteration had a calf tethered to a palm on a sodded median strip. Seated among these countrified props, Sherk extended her sitting performances into a more social vein, inviting participants, all to show how a city could be made more livable. Soon, these actions morphed into the project for which Sherk is best remembered, The Farm (1974-1980).

Using business skills gained from installing Portable Parks, Sherk, in 1974, secured rights to a property she called Crossroads Community, aka The Farm, a seven-acre site at the junction of Army Street (now Cesar Chavez) and Potrero Avenue, a forgotten, despoiled piece of land at the edge of the city. In so doing, she co-opted the popular idea of an artist-run organization and took it in wholly original directions, hosting performances, exhibitions, screenings, readings and related cultural events. However, it also had a modest farm and animal enclosures visited by thousands of school children on field trips over six years of operation. It was a rare and memorable occasion when cutting-edge artistic practice embraced primary education at a grassroots level.

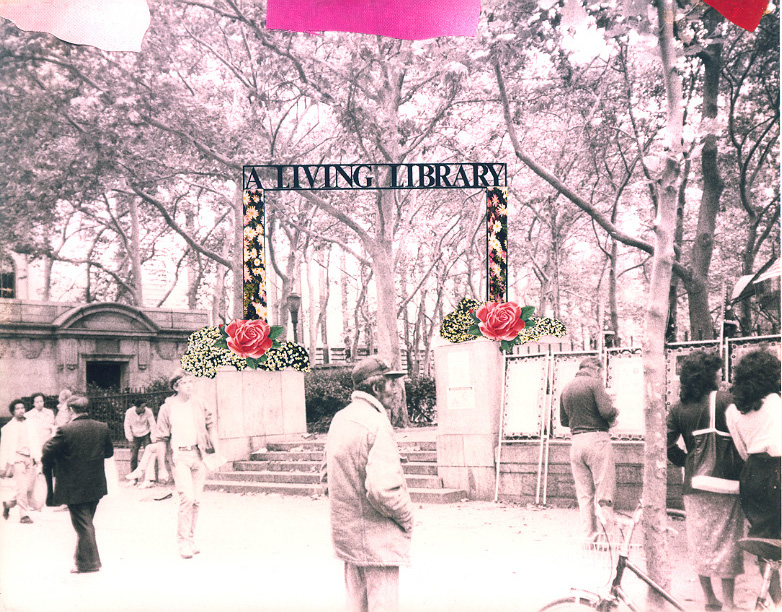

The first two-thirds of Sitting Still documents Sherk’s work between 1970 to 1980. When the Farm closed, Sherk moved to New York and turned from outsider strategies toward agitating in more socially acceptable modes. The exhibition concludes with documentation of her many professional, landscape-architectural proposals for permanent park-like installations in cities worldwide. The artist’s organization, A Living Library, survives her, promoting urban redevelopment projects that combine ecological practices, education, visual richness and human interaction with flora and fauna. Sherk emerged during an era in San Francisco when sculptors, musicians, photographers, provocateurs, activists and aesthetes found common ground in making progressive changes in American culture. While interdisciplinary thinking of this sort is now common because of the Internet, Sherk was in the vanguard, at the center of a group of young artists in an analog world who anticipated these possibilities 50 years ago.

# # #

Bonnie Ora Sherk: “Life Frames Since 1970” @ Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture through March 10, 2024.

About the author: Renny Pritikin was the chief curator at The Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco from 2014 to 2018. Before that, he was the director of the Richard Nelson Gallery at UC Davis and the founding chief curator at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts beginning in 1992. For 11 years, he was also a senior adjunct professor at California College of the Arts, where he taught in the graduate program in Curatorial Practice. Pritikin has given lecture tours in museums in Japan as a guest of the State Department, in New Zealand as a Fulbright Scholar, and visited Israel as a Koret Israel Prize winner. The Prelinger Library published his most recent book of poems, Westerns and Dramas, in 2020. He is the United States correspondent for Umbigo magazine in Lisbon, Portugal and the author of a recently published memoir, At Third and Mission: A Life Among Artists.

How splendid to read this article! I remember going to The Farm as a young artist, but wish I had met and known Bonnie Sherk. Thanks for review.

Finally, some notice for a female artist whose early works in the Bay Area were ground breaking and whose history has been ignored by the local art support system. Thanks to Renny for remembering and covering her exhibition. I only wish Bonnie could have been here for the opening herself. Too many women artists are being recognized after they are gone. The NY Times has been in the fast lane lately with the obits but where are the museums and galleries when the artists are alive? Carol Law

Thanx so much for your piece on Bonnie. Felt close to her work from the get-go.

David Hyry

Very happy to read about this exhibition. Thank you!