by David M. Roth

Few exhibitions in recent memory have evoked the beauty, glory, tragedy, triumph and struggle of Black Americans as powerfully as Bryan Keith Thomas’ Tufted Cotton: a dense, multi-part installation culled from the artist’s museum-quality collection of Americana. The title, which alludes to slavery’s chief agricultural product, is a mere jumping-off point for a sweeping – and sometimes overwhelming — display of hybrid artifacts that gives fresh meaning to the Civil Rights-era slogan “Black is beautiful.” It leaves few aspects of African-American history and culture unexamined. The results, reflecting that history, range from gut-wrenching to majestic.

In it, you’ll find ornately framed 19th-century photos, assemblages built around church fans, antique furnishings, textiles from Africa, Asia, and the Americas, paintings, flower arrangements, clothing, books, ceramic figurines, musical instruments and much else. They infuse the gallery with a gothic sensibility redolent of the church-going culture into which the artist, 46, was born in Dyersburg, Tennessee (population: 16,024).

Thomas’ family, I’m told, was affluent, yet the accouterments you’d expect to find in such households were curiously absent. His discovery of them in the homes of older relatives and neighbors set him on a quest to connect with his ancestry by amassing Black Americana. Fashioned into fetish-like assemblages and set pieces, these objects give off serious mojo, their innate power as significant as the transformations Thomas enacts upon them.

Humble church fans, evoking sweltering southern climes and gospel choirs, for example, rank among the show’s most potent offerings. They appear variously, as opaque black “mirrors” bearing locket photos, tassels, rose blossoms, geodes and other ephemera; as gold-painted panels sporting faded photos; and, most memorably, as part of an assemblage called Forever Free, a wood panel supporting a fan decorated with floral patterns, below which can be glimpsed a partially occluded photographic portrait of enslaved men and women. To the bottom of the panel, the artist appended pin-pierced heirloom bags filled with hair, seeds and crystals – remnants of syncretistic religious practices that still prevail in Africa, Asia and parts of the Americas. In a video produced by CCA, where Thomas teaches painting and drawing, he describes a hometown neighbor applying water to bags of precisely this sort, treating them as if they were living things. That notion apears to undergird everything the artist does, including his transformations of more tangible things, like the ceramic Mammy figures that once served as cookie jars. Thomas adorns two of them with haloes, effectively conferring sainthood on servants, each displayed in a bell jar on chest-high architectural columns.

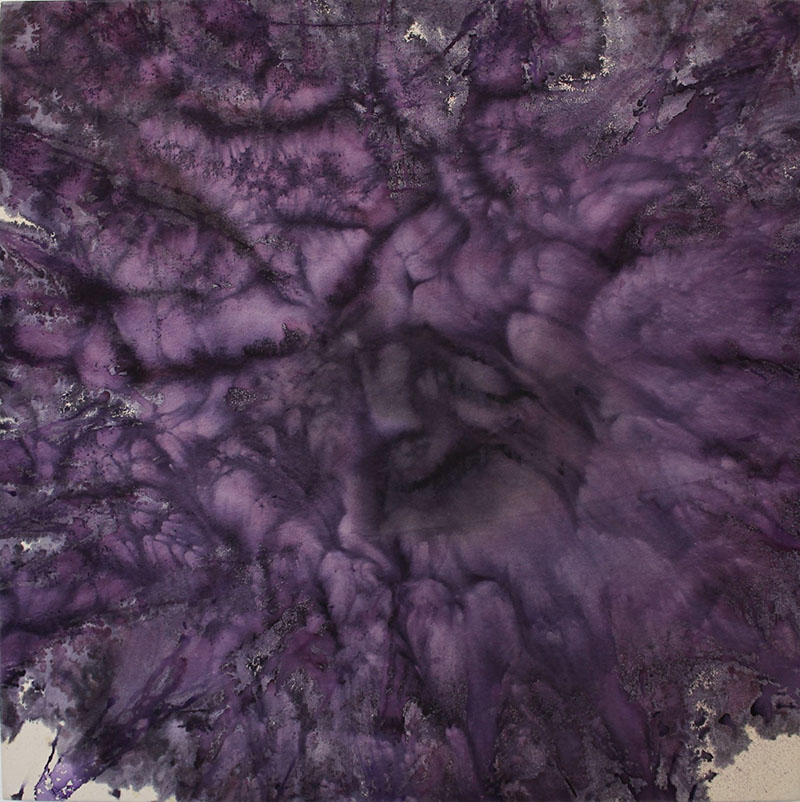

Lest anyone think Thomas a mere conjugator of antiquities, consider his remarkable forays into abstract painting. These mirror-like works, which resemble pools of congealed obsidian, reflect faces as dark shadows: visible, but just barely. The reflective parts share space on each panel with rough, pumice-like segments, making for surfaces that look like they’d been spewed from an active volcano and then scoured by receding glaciers. Several such works including, Black Roots, have fan-based assemblages appended to devastating effect. As declarations of blackness go they have few equals.

Thomas’ selection of vintage photos is noteworthy, too, for how the subjects pictured meet your gaze with palpable force, a rarity in 19th century when long exposure times typically yielded inscrutable results. Those unearthed by Thomas read like open books, their personalities available to anyone who cares to look. He also explores women’s fashions, in particular those worn on Sundays. Several wire-frame mannequins clad in period finery occupy a corner of the gallery along with a collection of tambourines — indicators of where those clothes were worn. One of those garments is a full-length coat made from the skin of a fetal lamb, its curly locks a mystery until the gallerist enlightened me. Elsewhere, in a display of textiles that includes Ghanaian Kente and Congolese Kuba cloth and American quilts, you can spot other cringe-inducing artifacts. The most prominent are a leopard skin draped across a sofa and a stool made from an elephant’s foot. They fill the space with a scent that falls somewhere between moth balls and dried dung. Under a bell jar in the same space, Thomas combines a bleeding-heart Jesus with the figure of screaming Black child. It’s title Somebody’s Calling My Name, comes from a Negro spiritual about death and salvation, and it questions the value and utility of faith. The apparent message: Faith, no matter how strong, couldn’t ease the pain of those suffering under the master’s whip.

Such assertions of blackness – and Black History — are, without question, politically charged given the chasm between Black and white culture during the Jim Crow era, the time period referenced by most of what appears here. A crystal chandelier bearing cotton bolls underscores that point, pitting an emblem of slavery against another symbolizing the vast (and unequally distributed) wealth it produced. Likewise, an angry Sambo figure buried in a small cotton bale surrounded by fetish objects makes the same point more emphatically. Nearby, in an area of the gallery filled with comfy antique chairs which you’re welcome occupy, Thomas, in his professorial role, provides a well-chosen selection of books for those who want to learn more.

Thomas is not the only artist mining Black history under the banner of truth, beauty and pride. The list of contemporary artists doing so is a long one; it stretches from Betye Saar and Robert Colescott to Kara Walker and Kerry James Marshall and from Carrie Mae Weems and Glenn Ligon to a cohort of younger artists too numerous to list. The difference between Thomas and the latter group rests with his pan-national, socio-anthropological approach to object collecting and his Faulknerian view of the past as a continuum. By dint of the artist’s near-psychic connection with those objects and his ability to juxtapose them for maximum impact, Tufted Cotton brings the past into the present in ways any viewer, with or without Thomas’ life experience and heritage, can sense and appreciate.

# # #

Anglim Trimble’s ground-floor space features a group exhibition of painting and sculpture that could serve as a primer on contemporary abstraction. It’s a knockout. Titled In a grove after the Philip Lamantia poem of the same name, it contains works by Thomas Akawie (1935-2019), Brad Brown, Mason Dowling, Donald Feasél, Renée Gertler, Robin McDonnell and Nancy White. The theme, writes the curator, Dean Smith, is “the elusive and terrifyingly ecstatic nature of our attempt to decipher the language of the godhead–whose unknowable aspects lie beyond actions or emanations.”

In varying degrees, all of the participating artists evoke those aspects, none more than Feasél whose works, Ashden and Citadel #19, feature pillowy amorphous formations that look more like gentle exhalations than anything realized through brushwork.

Akawie’s two paintings, Blue Escutcheon and Sunset Mirror, combine geometric Precisionism, ethereal fields of airbrushed space and decorative patterns that appear in Native American crafts. The result is a kind of desert mysticism that would look right at home alongside works made by the Transcendental Painting Group (1938-1941). Nancy White’s paintings exhibit similar geometric shapes rendered in muted colors, so much so that you have to look hard to discern them. Mason Dowling’s scratchy paintings are as significant for what they omit as for what they reveal; Gila the strongest of the pair on view, gives off the look of a fossilized reptile exposed by an archeological dig.

oil on wood, 14 x 11 inches

Brad Brown’s paintings are the product of an iterative process that involves salvaging pieces from prior works and incorporating them into new paintings subject to continuous revision. To understand how they evolve, it helps to see them en masse as I did in a solo exhibition four years ago. Here, we get just four examples: a mere glimpse. Still, it’s enough to grasp the beguiling character of compositions that change over time spans ranging from ten to 15 years.

McDonnell’s and Gertler’s small-scale sculptures also skirt easy categorization. Gertler’s, made of plaster, paper and industrial materials dominated color-wise by something close to Yves Klein blue, and McDonnell’s, done in Styrofoam drenched in glowing iridescent colors, bring to mind what, in the 1960s, was called space junk: orbiting objects that fell to Earth and were subsequently altered upon re-entry. Language of the Godhead? No. Otherworldly? Most definitely.

# # #

Bryan Keith Thomas: “Tufted Cotton” and “In a grove” @ Anglim Trimble Gallery through February 24, 2024.

About the author: David M. Roth is the editor, publisher, and founder of Squarecylinder, where, since 2009, he has published over 400 reviews of Bay Area exhibitions. He was previously a contributor to Artweek and Art Ltd. and senior editor for art and culture at the Sacramento News & Review.

Yes! Loved these shows and great to see them get some wider attention.

Two great shows, as are your reviews, appropriately. Thanks for writing about them!