by David M. Roth

A defining moment for Jacqueline Humphries came in 1985 when she was enrolled in the Whitney Independent Studies Program. The program was ruled by high theory and defined in large measure by a towering disdain for painting. To continue that practice, her colleagues argued, would be career suicide, a warning Humphries, 63, took to mean she was on the right track.

In the decades since, she’s dedicated herself to reinventing the medium by cannibalizing its recent past (AbEx, Op, Minimalism) and mixing in the cold, impersonal iconography of the Internet. The goal, she says, is to make paintings that are as addictive as, say, video games, Facebook, Instagram or Tik-Tok. Toward that end, she developed an arsenal of visual devices to sow perceptual confusion. The most significant is a recursive library of abstract gestures, forms (dots) and symbols (emoticons, emoji, ASCII characters, CAPTCHA codes) that she applies to canvas through stenciled layers – reworked from one painting to the next in ways that make it difficult to differentiate between manually made forms and those created by digital or photo-mechanical means. These methods translate well to printmaking.

Seventeen such works (made between 2016 and 2023) on view at Crown Point Press form a telescoped survey of the artist’s techniques and concerns. The most recent feature grids of dots topped by paint splatters taken from Just Stop Oil activists who, in 2022, threw tomato soup at Van Gough’s Sunflowers in Britain’s National Gallery. Humphries employed the stain not for its political/artistic shock value or to lend credence to politically motivated vandalism but for its similarity to forms she’d painted earlier. Its spidery cascades – bent, stretched and cropped – appear in different colors against backdrops of contrasting hues, the names of which double as titles. When looking at them, it’s easy to feel something of the stick-it-to-the-man glee experienced by vandals and graffiti taggers. But the series’ most compelling characteristics arise from things that rest at the edge of perception: faint, vaporous clouds that seem to drift among the dots and skyscraper shapes that, in one work, Untitled (Sienna), leap out from the lower left corner only to mysteriously disappear when you try to bring them into focus.

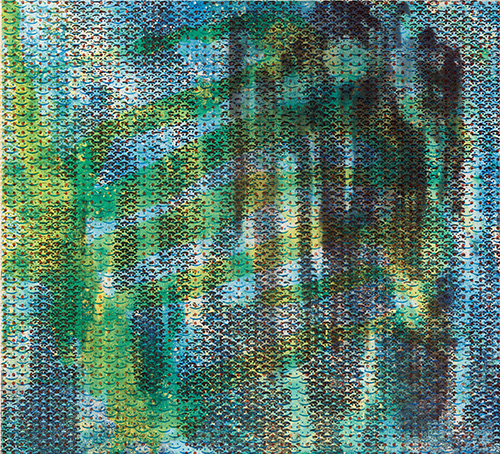

Like Warhol, Rauschenberg, Johns, and Lichtenstein, Humphries, one of this era’s most revered conceptual painters, realized early on that the medium’s continued relevance hinged on the degree to which its practitioners could picture contemporary experience. For her and similarly inclined artists like Laura Owens and Amy Ellingson, that meant adopting the visual argot of the Internet. In triple emoticon titled work from 2016, for example, she imprinted hundreds of emoji over an undulating blue-green-yellow wash, upending them to look like eyes. The effect is of a work of art surveilling you, a deft expression of what it means to use a smartphone or any other Internet-connected device.

Other works from the same year exhibit very different traits. One, identified only by a cat emoji, repeated (sans facial features) in various sizes across a grid, carries bold, black surface marks resembling fragments of a hexagram. Geometric shapes of a similar sort also overlay another print in which turbulent waveforms rendered in brushy strokes call to mind what Hokusai might have come up with had he painted underwater currents.

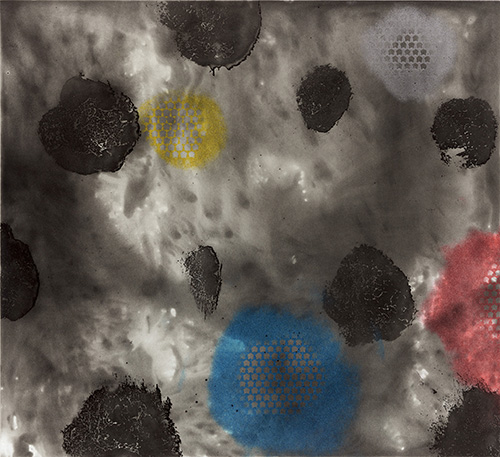

Two other works, ogv and ryb (both 2016), feature fractured black blobs and honeycomb shapes floating atop sooty grounds that could have been produced by fumage, the practice of using smoke to create images. In these, interest derives less from surface shapes than from spectral light emanating from deep within, echoing Ross Bleckner’s early works.

Whether paintings of this sort, designed to reference the virtual life and its attendant vagaries, will win over screen-addicted millennials is an open question. As is, Humphries’ art continues to reward long looking.

# # #

Jacqueline Humphries @ Crown Point Press through March 22, 2024.

About the author: David M. Roth is the editor, publisher, and founder of Squarecylinder, where, since 2009, he has published over 400 reviews of Bay Area exhibitions. He was previously a contributor to Artweek and Art Ltd. and senior editor for art and culture at the Sacramento News & Review.

Love the work you show, and your discussion of it!

Great review, Dave! I love Humphries’ work– so smart, and getting better all the time.