by Mark Van Proyen

Traditionally, art has commemorated people, places and events, lest they be lost to the sands of time. But what happens when those shifting sands are the things being commemorated? Matthew Picton’s exhibition of ten recent works provides fascinating answers. The dates of these works range from 2016 to 2023, pointing to the labor-intensive nature of the artist’s process. Using archival pigment, he prints digital photo collages onto archival paper of varying thicknesses. He then undertakes the painstaking process of cutting elaborate perforations into the printed material before reassembling the pieces in two or three layers suspended atop one another with about an inch between them. When you walk past these works, the perspective shifts subtly, creating an enlivening animated effect.

The net results of this process are very similar to those seen in diachronic maps, used by archeologists to display layers of an excavated site to show how it evolved from one phase to the next over time. In Picton’s work, this representation of time is signaled by layering and his presentation of cities (or city maps) from high altitudes.

The City of London, 1700 to 1900 (2020), the largest work on view, is a good example. It consists of five adjacent vertical panels connected by the River Thames, which snakes horizontally through them from left to right. It is the darkest work in the exhibition, reflecting the Dickensian London of the 19th century. It bespeaks a dirty urban landscape covered in coal soot and drenched in desperate poverty, a fertile hunting ground for Bram Stoker’s famous vampire, Arthur Conan Doyle’s intrepid detective and Oscar Wilde’s immortal dandy.

Venice, ‘Casanova’ (2016) looks down on the famous island city, revealing the winding canal and details of its labyrinthine street plan with cut paper perforations. In this instance, Picton employed posters from Federico Fellini’s 1977 film Casanova, which he cut and reassembled to locate aspects of the film’s story near the time and place of its original 18th-century telling. At once opulent and decrepit, the Venice of Casanova’s time, as Picton captures it, is a hive of historical ghosts that point to the story of its most famous citizen.

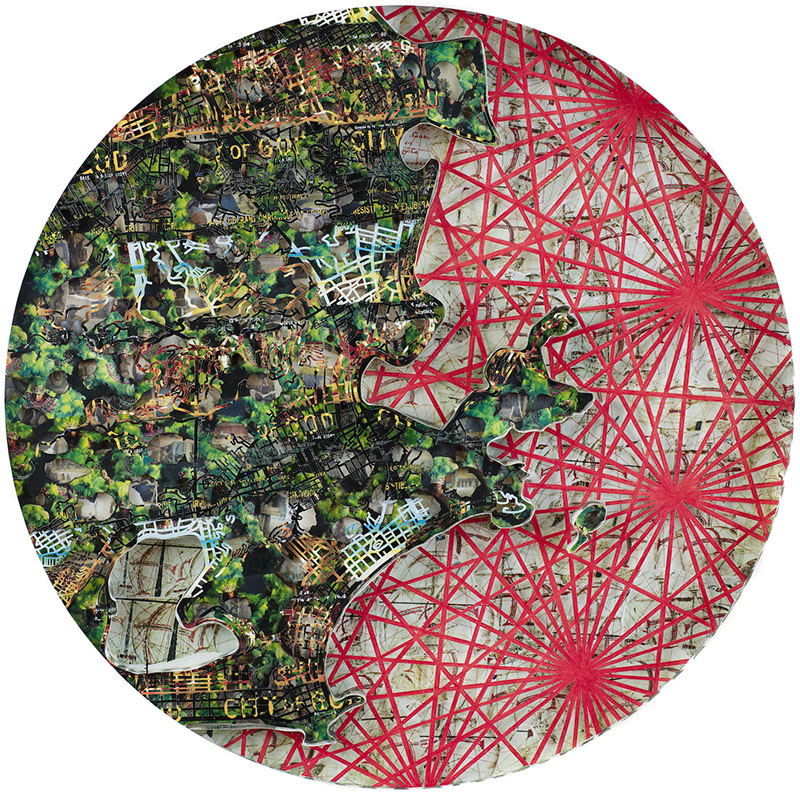

Rio De Janeiro and ‘The City of God’ (2017) differ in that they’re done in a circular format. In these, Picton doesn’t recapitulate the street plan of that famously chaotic Brazilian city; instead, he conveys it by bisecting the composition vertically. On the left side, we see the encroaching jungle, while the right shows an array of radiating red stripes that are less a representation of boulevards than they are a salute to the Apollonian stylistics of Brazilian Modernism, better realized in the famously sterile capital city of Brasilia than in Rio’s outlying Dionysian jungle and interior favelas. The title City of God refers to a 2002 film directed by Fernando Meirelles, reflecting hardscrabble lives in Rio, a subject to which Picton’s piece seems only tangentially related.

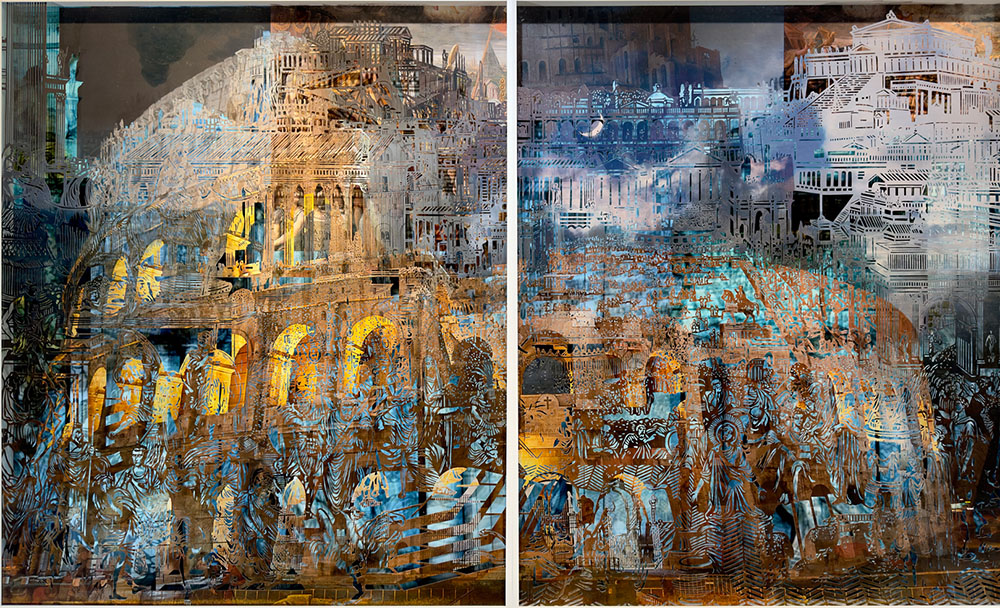

Some of the works do not use overhead vantages. Forum, a two-panel work, looks at the Coliseum from ground level, alluding to when it was used to make popular spectacles of Christian persecution. The building is portrayed at night, bathed in the kind of light that we might associate with the premier of a major motion picture. Does the piece celebrate the anti-Christian legacy of the building, or does it make a more general comment on the use of Bread and Circuses to placate and manipulate the proverbial mob? Either way, it is a stunning piece that reflects on a historical quagmire central to Western civilization: the hidden mendacity memorialized by “heroic” monuments.

All of the work Picton presents in this exhibition portrays places of historical centrality, but it does so by reflecting second-hand, quasi-fictionalized accounts of them, slyly destabilizing their implied triumphalism. The ornamentation of the layered cut-paper technique facilitates the visual transition from material site to connotative narration, showing how the latter supersedes and displaces the former in the realm of cultural reflection, proving, among other things, that we no longer have to be there because there is less an actual place than it is a hall of oblique mirrors.

# # #

Matthew Picton: “A Seeker’s Paradise” @ Nancy Toomey Fine Art through March 15, 2024.

About the author: Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries emphasize the tragic consequences of blind faith in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak’s interview on Broke-Ass Stuart’s website.