by Mark Van Proyen

Rico Solinas’ current exhibition, containing well over 50 paintings dating from the past 35 years, may not reach the threshold of a full-fledged retrospective, but it will suffice until such a exhibition comes along. During the past three decades, Solinas has been prolific in making urban landscape paintings while working full-time as a preparator at SFMOMA.

Not counting a few undated early works, the bulk of the paintings in this exhibition are clustered into thematically distinct subgroups. One is an array of 24 tondos that reveal elements of a topsy-turvy urban landscape as if distorted through a fisheye lens, usually staged from a dramatic low angle that looks upward to a vibrant blue sky. Several of these feature contorted street signs, such as Kwik Way Drive Up (c.1990), where a commercial street sign snakes upward into the picture like the tentacle of an octopus. Others picture buildings from an exaggerated perspective, such as Untitled (Montgomery Street Lamp) (c. 1990s).

Another cluster depicts maritime scenes rendered in a range of grim storm cloud colors, often including choppy waves that rise like white-capped thorns. This group of paintings was executed in 1990 and composed on rectangular canvases hung off-kilter to mirror the impending turbulence of the scenes portrayed. The majority depict naval vessels setting forth on journeys, such as SSN591 Shark, which shows a vintage 1960s-era submarine traveling unsubmerged amid an ominous darkness. FF1050 Gray has a US Navy frigate proceeding into the unknown under a bright blue sky, surging ahead atop churning waves worthy of Winslow Homer.

The most recent works, smallish gouache-on-paper pieces, date from 2020 to 2023. They’re part of a series called The Bayview, focusing on an economically distressed neighborhood in southeastern San Francisco. Many of these paintings feature buildings corresponding to addresses declared by their titles, such as 1499 Thomas Street, portray a two-story pink building with a bright green awning on the ground floor. Passing figures seem like normal features of a social landscape teetering on the brink of imminent gentrification, recalling transformations that happened to the Mission District 30 years ago. A few other paintings feature tricked-out vintage cars that seem like homages to Robert Bechtle’s 1970s photorealism.

That said, it is still hard to tell if or how much Solinas uses photographic source material to develop his paintings. In many instances, they look as if they were executed en plein air, even though the representation of their subject matter is always crisp and precise.

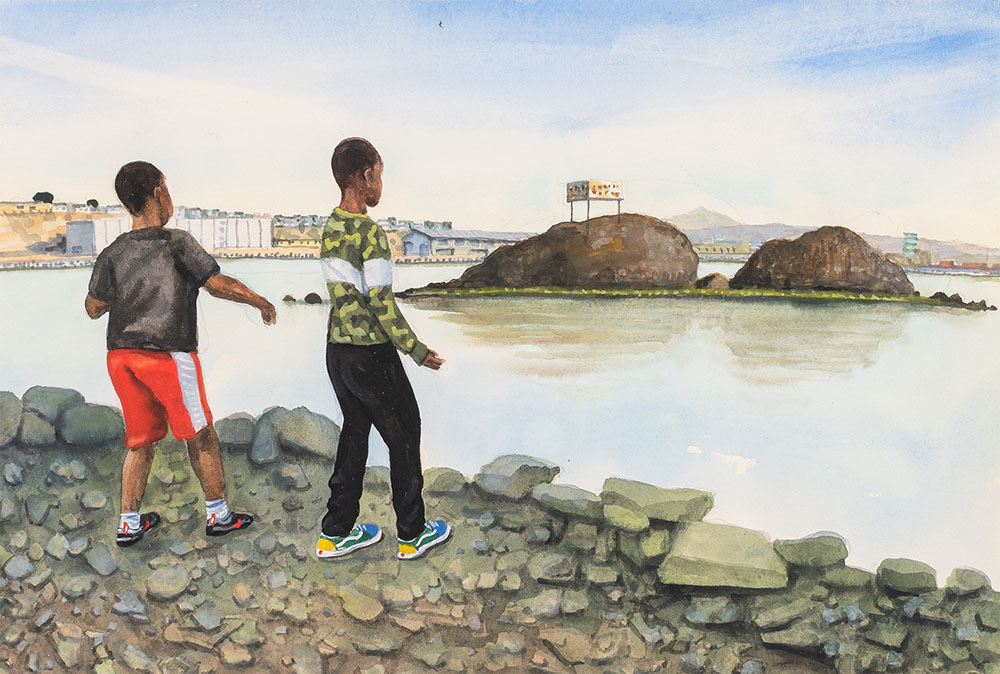

Some paintings, such as Double Rock, Trey and Jamal and Hunter’s Point Shipyard, emphasize figures. In these, we see precocious tweeners rendered in a style that harks back to the gritty urban realism practiced in New York during the 1920a by the likes of John Sloan and William Glackens. The figures also seem

slightly distorted and cartoonish, subtly hinting at Robert Crumb’s obstreperous cast of underground comic characters. These works move in a different direction from Bay Area Figuration in that they are less about painterly pyrotechnics and much more about the social meaning of real people. They show the Bay View neighborhood in a positive light, populated by everyday people who defy the stereotypes of impoverished criminality so often applied to this community. They are bitter-sweet and even a bit gritty in some ways, but the dominant mood is optimism and compassion.

In many respects, the Bay View series comes full circle to the larger undated early works such as Barber College (n/d). The difference is that those early works are executed in thicker and looser applications of oil paint. Nonetheless, they also hark back to Ashcan school realism of the 1920s, begging the question: Why is this kind of realism now? The answer lies in how it contradicts the technological hyperregulation of images that presumes to define the social world without living in it, providing maps only vaguely related to the territory represented. Solinas’ paintings do the opposite by discarding the map maker’s presumptions of comprehensive understanding, with all the overreliance on artificial intelligence and virtual reality simulation. Instead, they focus on the nuanced particularities of local color and the everyday heroism of real life in the circumstances in which it’s lived.

# # #

Rico Solinas: “You Never Know” @ Anglim Trimble Gallery through April 27, 2024.

About the author: Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries emphasize the tragic consequences of blind faith in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak’s interview on Broke-Ass Stuart’s website.

Wonderfully curated exhibition of Rico’s passion and his range in painting. Great to see a Bay Area painter wholeheartedly presented and reviewed. Kudos.

Fabulous show, not to be missed. And Mark, your observation, ” … everyday heroism of real life in the circumstances in which it’s lived.” says it all. Rico is the ultimate Ambassador of the Bayview!