by Renny Pritikin

William Scott’s cinemascope-scaled mural Praise Frisco: Peace and Love in the City virtually rushes up to greet visitors with the enthusiasm of a long-lost relative. Its exuberant colors and narrative imagery depict Scott’s family and friends firmly grounded in a fantastical Bay Area visual culture. His Americana-influenced style, that of carnival posters, ads for magicians and painted photo backgrounds, argues that we are shaped equally by the geography, architecture and people around us. Scott’s deliriously enthusiastic 32-foot-long acrylic mural, commissioned for the entrance to The House that Art Built, begins SFMOMA’s new group show of artists from Creative Growth, the renowned East Bay art program for the developmentally disabled.

The institution’s origins trace to historic political decisions made when Ronald Reagan was governor of California, a time when progressives argued that warehousing developmentally disabled and mentally ill people in large state-run institutions was morally indefensible. Republicans saw an opportunity to cut government spending by shutting down places like Napa State Hospital. In so doing, they also chose to eliminate ongoing care for those former residents when they returned to their home communities.

29 x 16 x 21 inches

In response, Florence and Elias Katz, an East Bay couple, took it upon themselves to modestly address the problem. In 1974, they started Creative Growth, an art education program in their own home, which, half a century later, has grown to become a widely emulated national model for such efforts. In the mid-1980s, the Katzes went on to found two sister organizations: Creativity Explored in San Francisco, and NIAD (Nurturing Independence through Artistic Development) in Richmond, both of which are still thriving, and whose artists will be included in future SFMOMA exhibitions.

Today, Creative Growth, which operates a large facility in downtown Oakland, serves 140 artists a year. Together, the three organizations form a unique support system for artists in which the participants work closely with artist-teachers who suggest themes, materials and formats. Over the years, several artists associated with the program have achieved wide attention and strong sales, including the late Judith Scott, who wrapped found objects in yarn and string, and Michael Loggins, who wrote the poignant Fears of Your Life, selections from which were published in Harper’s magazine.

The House that Art Built celebrates the organization’s 50th anniversary and initiates a new commitment by SFMOMA to support artists previously outside the museum’s scope. It showcases selections from a newly purchased cache of some 80 works by 11 Creative Growth artists dating from 1981 to 2021, as well as the Scott mural commission, one of the exhibition’s highlights.

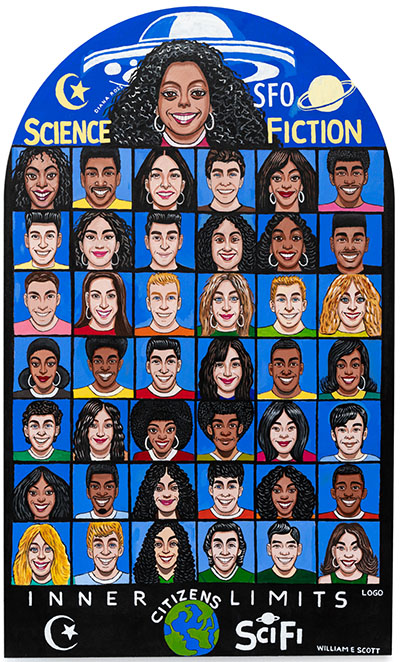

Praise Frisco derives from Scott’s experience growing up in Hunter’s Point, where he witnessed so much violence that art became a haven for him, a place to find peace, happiness and safety. The mural depicts a stylized San Francisco skyline as seen from Twin Peaks, with Market and Van Ness Streets dominating the left half of the mural and a low-rise neighborhood I take to be an East Bay location on the right. Sprinkled throughout are glamorous portraits of African American people and Scott himself: nostalgic manifestations of people in his life, particularly the artist and his mother when they were young. (Scott is 60). Depictions of real people, as they appeared in their lost youth, establish a fantasy context for Scott’s paintings, in which it is not out of the ordinary for a Mickey Mouse arch, for example, to appear over Market Street. However, Scott’s highly skilled draftsmanship grounds the work in reality. Text throughout refers to a future San Francisco—still with London Breed as mayor—transformed into a “gospel Disney” paradise in the 2030s and 2040s, occupied by happy “future families.” The overall effect is one of energetic optimism and an embrace of sassy Black culture manifested in elaborate hair, sexy clothing and beautiful smiling faces.

Ten mixed media self-portraits on paper by Camille Holvoet are imbued with a gentle, occasionally sardonic humor. Her deadpan titles and bemused facial expressions reveal a self-aware artist navigating the world of doctors, group homes and private life despite her challenges. She arrives at a new living facility with her suitcases in Camille Is Moving to a New Home, Holvoet’s only piece that depicts architectural space—quite well—rather than her usual figure/ground constructions. She appears hopeful if unsure about her changed circumstances. Two works about obsession-fueled insomnia reveal relatable vulnerabilities; they show her agitated brain, seen through a window in her forehead, wrestling with words. She courageously smiles through an EEG exam with multicolored electrodes arrayed around her head like so much candy. Holvoet doesn’t self-censor. In a startling, frank image, she depicts herself nude in bed, surrounded by donuts, cupcakes and other treats, graphically masturbating. In another piece, she hilariously considers the complexity of gaining income from sales of her work—piles of coins and cash are seen—which triggers concern about taxation and the threat of losing her SSI support, a frequent problem for these artists.

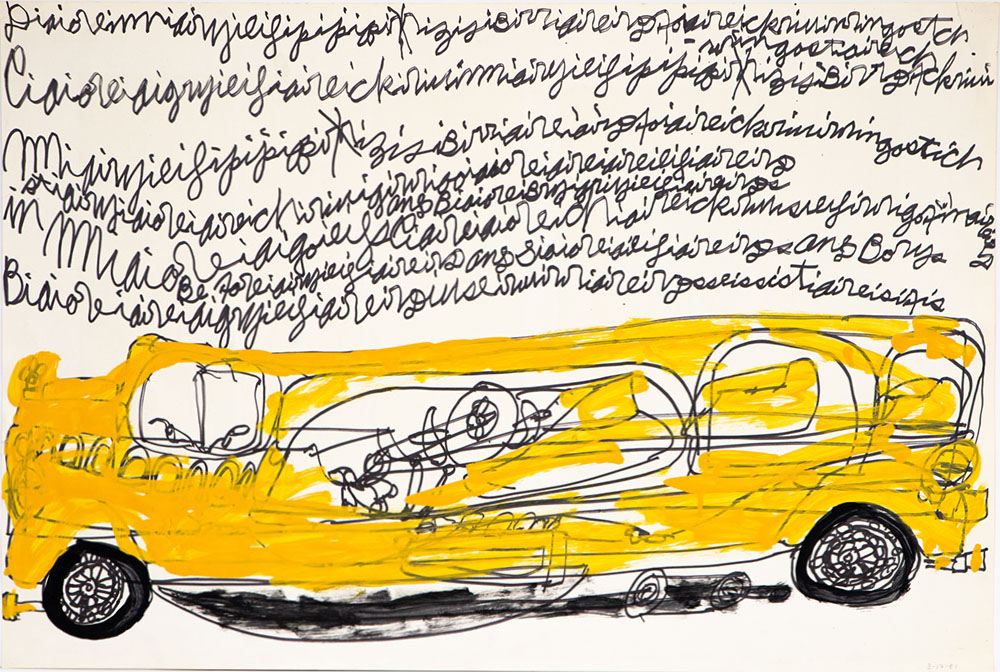

The curators chose a large abstract painting by Joseph Alef as the signature image for the show. While the piece is dramatic and reminds me of early Jackson Pollock or late William T. Wiley in structure and juxtaposition of colors, it feels like an odd choice, as it echoes any number of works that might be found in the Fisher Collection. Another abstractionist, Dan Miller, centers scratchy lines of overlapping color on one page; a second; is made up of circular shapes that recall those seen in the paintings of Joan Moment.

William Scott attended the press reception for the exhibition and dominated the room. Tall and slim, he wore black pants, a white shirt with a black tie topped by a black Stetson. The gallery dedicated to his work exudes a similar commanding presence. In one, he painted faces over a found men’s sport coat to hilarious and charming effect. Elsewhere, knockout science fiction paintings mix Afrofuturism with high school yearbook nostalgia. One unforgettable piece, a double self-portrait nude from the waist up, labels the figure on the left as the old William and the one on the right as the new version. Between them, he places the words “God’s Plan.” A nasty scar on the torso of the older figure goes missing from the new version.

Portraits by Ron Veasay are the exhibition’s great discovery. Veasay bases his work on images found in art history books. His translations transform the original material so thoroughly that the sources are not readily apparent. Veasay concocts recognizable personae and emotional states in his faces, augmented by a rich color sense. In what I take to be his version of Botticelli’s Portrait of a Lady, the subject is surrounded by an unusually rich sienna. In another, a lovely mottled blue backgrounds a woman sporting a large Afro, making eye contact with an insouciant shrug of her shoulders.

The House That Art Built is a relatively small show, but it’s supported by thorough research. Ephemera, such as the original Creative Growth neon sign, discovered in storage and refurbished for the exhibition, shows up along with early advertising posters and a helpful timeline. There are two video works: a fashion show that feels a little uncomfortable, and an odd, provocative interview with one of the artists who fails to answer questions she asks herself in a voiceover.

Art of this sort is rarely integrated into mainstream museum’s regular programming; instead, it’s too often relegated to speciality art fairs, dedicated museums, or isolated in group shows. SFMOMA has taken a significant step toward equity by committing to show the work of developmentally disabled artists on an ongoing basis; it would be satisfying to see it integrated into the permanent collection galleries. The House That Art Built demonstrates the complexity, humor and canny perceptions offered by such work. That these artists inhabit the same world with the same concerns as everyone else is a truism too often overlooked.

# # #

“Creative Growth: The House That Art Built” @ SFMOMA through October 26, 2024.

About the author: Renny Pritikin was the chief curator at The Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco from 2014 to 2018. Before that, he was the director of the Richard Nelson Gallery at UC Davis and the founding chief curator at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts beginning in 1992. For 11 years, he was also a senior adjunct professor at California College of the Arts, where he taught in the graduate program in Curatorial Practice. Pritikin has given lecture tours in museums in Japan as a guest of the State Department, in New Zealand as a Fulbright Scholar, and visited Israel as a Koret Israel Prize winner. The Prelinger Library published his most recent book of poems, Westerns and Dramas, in 2020. He is the United States correspondent for Umbigo magazine in Lisbon, Portugal and the author of a recently published memoir, At Third and Mission: A Life Among Artists.

Wasn’t Sylvia Seventy the original director of Creative Growth??

I don’t see her name mentioned and wonder if I’m wrong??

It’s a reasonable question but I was writing an exhibition review and not a history. The current director has been there for 25 years.