The Great Migration is a term that conjures myths and historical facts. Fact: From 1910 to 1970, an estimated six million African Americans fled the racial violence of the Jim Crow South to seek better opportunities in the North, the mid-West and West Coast urban centers of the United States. The myth, embodied in Jacob Lawrence’s memorable cycle of 60 paintings titled The Migration Series (1940-41), idealizes the perils of that journey to freedom as a kind of Biblical exodus to a promised land. Lawrence made those paintings at the zenith of the Harlem Renaissance as a reflection on the struggles and accomplishments leading up to that moment, giving visual and narrative form to a distinctly African American history that was beginning to take shape. Now, more than eight decades later, the Great Migration is being revisited in an intergenerational exhibition of 12 African American artists working in diverse media and locations. If Lawrence’s cycle was an attempt to give mythic shape to a shift of population in the first half of the 20th century, we can then say A Movement in Every Direction expands Lawrence’s project, adding new and more elaborate layers of personal storytelling to the continued search for sanctuary, while remembering haunted places left behind.

Jessica Bell Brown and Ryan N. Dennis of the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Mississippi Museum of Art curated a Movement in Every Direction. Its arrival at BAMPFA marks the fifth stop on a two-year tour. The exhibition includes two publications, including a richly illustrated catalog featuring essays by Kiese Laymon, Sharifa Rhodes-Pitts and Willie Jamaal Wright. All of the works included in A Movement in Every Direction were specially commissioned for the exhibition.

Not only are the selected artists intergenerational, they are inter-reputational as well, ranging from widely known practitioners like Theaster Gates Jr., Mark Bradford and Carrie Mae Weems to relative newcomers such as Detroit-based Akea Brionne. Gates presents an installation titled Double Wide (2022) consisting of two major components: a recreation of a make-shift food service trailer specializing in pickled goods fashioned from recycled lumber and a video lounge ensconced in a wooden box somewhat smaller than a standard shipping container, its interior painted lurid red, illuminated by an overhead bank of fluorescent light fixtures. The catalog says the piece is based on Gates’ childhood memory of his uncle’s farm in Mississippi. The title refers to two mobile structures that doubled as a food service station and an informal speakeasy and community center.

Bradford’s 60-panel painting titled 500 (2022) is an expansive work that repeats a handbill notice circulated decades ago, calling for 500 African American families to join a utopian community in New Mexico. The antique lettering of the original poster was done in high-relief caulking subjected to swiped applications of dark brown paint that echo the workings of old-style printing presses as well as Andy Warhol’s series of Disaster images from the early 1960s. The catalog suggests Bradford may have imagined his family’s move to southern California as being connected to the founding of that community, but that is conjecture, not fact.

Two bodies of work represent Weems, one a series of seven oval inkjet photographs titled North Star (2022), the other a video installation titled Leave! Leave Now! (2022). The photographs feature an image of the north star gleaming like a bright beacon, a reminder of how it helped escaped slaves navigate northward. Leave! Leave Now!, a 25-minute single-channel video, shows ghost-like images flickering between bright red theatrical curtains, revealing episodes of life in the Jim Crow era with context provided by a voice-over narration.

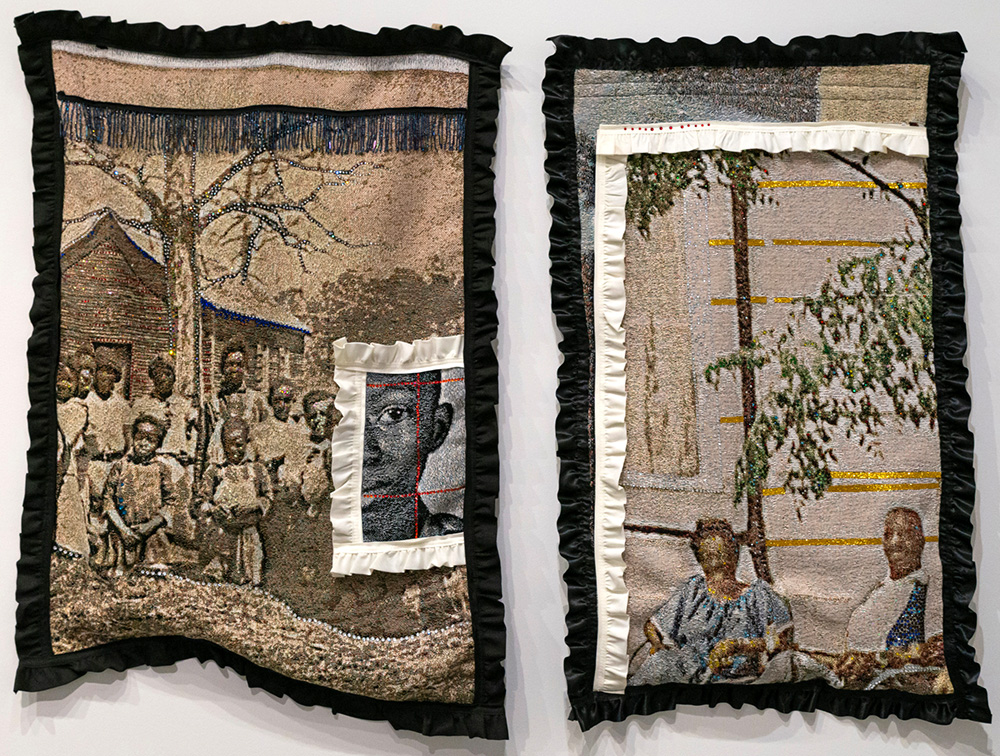

Detroit-based Akea Brionne’s six mixed-media works (2022) defy categorization. Titled An Ode To (You)’all, they consist of tapestries made from digital files, lacquered to give them an undulating shape accentuated by colorful thread fringes and gleaming rhinestones. Like many other works in the exhibition, these reclaim and commemorate ancestors and other bygone heroes into a lineage of resistance, with a subtle nod to Vodun conveyed by the works’ unusual amalgamation of materials. Large photographs (all 2022) by Washington DC-based Larry W. Cook examine landscapes in rural Georgia. Bucolic as these images are, they are also disquieting and ominous, intimating that they are the site of bad events. Nearby, a vitrine containing archival documents and images suggests what those bad things might have been. The problem is that these photos rely on prompts outside the images rather than cues within.

A Movement in Every Direction features several large paintings (or mixed media works) that function as group portraits. The Water Runs Deep (2022), a three-panel mixed media work by Detroit-based Jamea Richmond-Edwards, shows seven figures ensconced in a boat traversing a turbulent sea of eye-popping color. Because the figures’ faces appear near the top of the composition, they resemble presidents memorialized on Mount Rushmore, but in point of fact, they portray the artist and her family braving the Mississippi flood of 1927, an environmental disaster that displaced thousands of African Americans.

A Song for Travelers (2022), a portrait of 15 (mostly) African American figures on a white ground, by New York-based Robert Pruitt, contains an odd mix of differently costumed people: a prim woman in Victorian garb, others in Native American regalia, a Nation of Islam member and an Afro-futurist robot. Zoë Charlton’s Permanent Change of Station (2022), done in charcoal and gouache, depicts a woman dressed in a disheveled airforce uniform stepping into a tropical landscape that looks like southeast Asia. It tells a familiar story: that of African Americans enlisting in the military to better their lives by escaping Jim Crow or urban ghettos. My only complaint is that placards in front of the image depicting foliage seem extraneous and distracting.

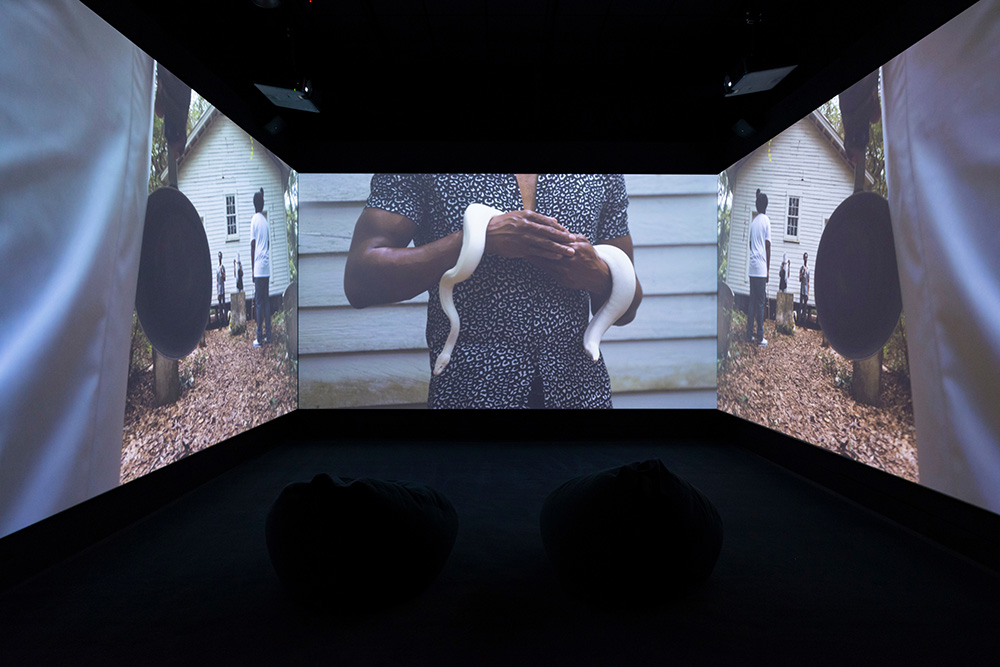

A Movement in Every Direction includes two other videos in addition to those provided by Weems. Allison Janae Hamilton’s 35-minute sequence of dancing ghosts inhabiting a Colonial-era Florida house conjures visions of antebellum life in sweltering swamplands. An absorbing and affecting showstopper devoted to the persistence of memory, it reminds us that many African Americans in the South elected to stay put rather than migrate. In Stefanni Jemison’s A*ray (2022), a 30-minute, single-channel video, Tick Tock performer Lakia Black works with an acting coach to improve her craft, dramatizing the tension between spontaneous and scripted communication. It’s charming and humorous, but its relationship to the exhibition’s theme is unclear. Even so, it does say something about the underlying pathos of self-packaging in the name of professionalism.

New York-based artists Torkwase Dyson and Leslie Hewitt deliver abstract installations. Dyson’s Way Over There Inside Me (A Festival of Inches) (2022) consists of four obsidian trapezoids connected by a black steel structure set at oblique angles. The reflective and translucent trapezoids resemble futuristic loudspeakers, echoing the work of Anthony Caro and Tony Smith. Hewitt’s three untitled floor works (2022) show glass objects contained and partially corralled by strips of hot-rolled steel and red oak: meditations on the condition of partial containment and the structures that translate personal histories into communal legacy. Both presentations are solid and sophisticated, but the connection to the great migration feels strained.

A Movement in Every Direction offers plenty of food for thought. The uncluttered installation confers dignity on the included works, affording viewers the opportunity to engage and absorb them without distraction. Indeed, the behind-the-scenes professionalism evidenced by the exhibition’s organization goes far beyond what passes for normal in the Bay Area art world, and that alone merits kudos.

# # #

A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration @ BAMPFA through September 22, 2024.

Cover image: Allison Janae Hamilton, A House Called Florida, 2022, three-channel film installation (color, sound), 34:46 min.

About the author: Mark Van Proyen’s visual work and written commentaries emphasize the tragic consequences of blind faith in economies of narcissistic reward. Since 2003, he has been a corresponding editor for Art in America. His recent publications include Facing Innocence: The Art of Gottfried Helnwein (2011) and Cirian Logic and the Painting of Preconstruction (2010). To learn more about Mark Van Proyen, read Alex Mak’s interview on Broke-Ass Stuart’s website.

Thank you for such a thoughtful reading of th exhibit. I really appreciated your article having seen the show and feeling puzzeled by the tiktock star and the black scuptures’s relationship to the theme of the show. .I also thought of Jacob Lawrence.having recently seen his work in the Phillips collection in DC.