by Maria Porges

Once upon a time, in the 1980s, I attended a talk by a famous New York artist. He reminisced fondly about the years he had lived in a cold-water fifth-floor walkup apartment in downtown New York, a place that cost so little he could pay the rent with one week’s work a month as a cabbie. Like Philip Glass—who, incidentally, kept driving a cab for nine years after the successful premiere of Einstein on the Beach—driving left this man with plenty of time to think and make work.

The “day job” is long established as one of the few near-universals in the lives of artists of all kinds. There are, of course, a favored few who almost instantaneously achieve the kind of prominence that guarantees financial success and long-term momentum, and others who inherit a cushion of wealth. A few more become monetarily successful after working hard for years. Aside from these lucky minorities, however, necessity has led artists to do many different kinds of work to make ends meet. With the possible exception of teaching, it is an unspoken truth that we are not supposed to talk about such things because that would mean we aren’t successful. So we labor in silence in a wide variety of careers.

Day Jobs brings together works by 36 artists who have engaged in a wide variety of employment (in everything except teaching and assisting other artists, about which I’ll say more later.) From the moment you enter the first gallery, the staggering ambition of such an enterprise becomes apparent—as well as the potential pitfalls of the attempt, however well-meaning, to address how artists have made a living since WWII: a period during which our society, what constitutes art practice, and the art world itself have changed cataclysmically. Framing the reason for this show, Curator Veronica Roberts notes, “More than ever, the art world—artists, collectors, museums, galleries, auction houses, art fairs—is perceived as a rarefied realm… defined by press headlines on auction house records involving unimaginable sums and lavish art fairs… The reality is that a very small proportion of the money that flows through the art world goes directly to artists.” (She cites the statistic that only about 10 percent of artists make a living from their work, which seems overly generous.)

Still, plenty of people believe in what Roberts refers to as “the fantasy of the artist sequestered in a studio, waiting for inspiration to strike.” Against this widely held supposition, she asserts, “Much of what has determined the course of art history in the late twentieth and early-twenty first centuries has been unanticipated, often accidental, discoveries brought about as much by everyday lived experiences as by dramatic epiphanies.” By these “lived experiences,” Roberts means jobs through which the vast majority of artists make ends meet. She describes being “stunned” to discover that Sol LeWitt had worked as a receptionist at MOMA, where Dan Flavin was an elevator operator and Robert Mangold and Robert Ryman worked as guards. This made such an impression on her that she began to collect stories of such mundane employment, even soliciting them from others in the field.1 And thus, this show came about.

Spread out over two floors in the Cantor’s expansive galleries, Roberts’ show presents a cross-section of the serendipitous inspirations that day jobs have offered. She asked colleagues and artists for recommendations, asking them to focus on those whose jobs “tangibly changed their practice.” She has organized the work in the show into six sections: “Art World,” “Media and Advertising,” “Service Industry,” “Fashion and Design,” “Caregivers,” and “Finance, Technology, and Law.” The categories of teaching and artist-assisting are too art-adjacent, in her mind, to be eligible, so they were left out. In “Art World,” there are pieces by figures such as Larry Bell (Untitled, 1959), whose stint in a framing shop was a springboard of inspiration for a lifetime of work with sheets of glass, and Fred Wilson (Grey Area (Brown Version) 1993).

Described here as a “freelance educator,” Wilson worked in several museums, absorbing ideas about institutional bias, display strategies and colonialism—all of which are visible in five heads of Nefertiti cast in skin tones ranging from white to black. (No mention is made of his other influential experience of museum employment as a guard.) Howardena Pindell’s practice was transformed by her full-time positions as an exhibition assistant and associate curator at MOMA. Unable to paint during hours of natural daylight, she began experimenting with scraps of paper and abstraction, as shown in her untitled piece from 1976.

It is not clear what connection Margaret Kilgallen’s mural-sized painting from 2000 has to other works in this room—she had a job at the San Francisco Public Library, which is not exactly part of the art world, and by the turn of the new century, was a graduate student in Stanford’s own MFA program (where, full disclosure, I was one of her professors during her last quarter in the spring of 2002). Still, it is lovely to see it.

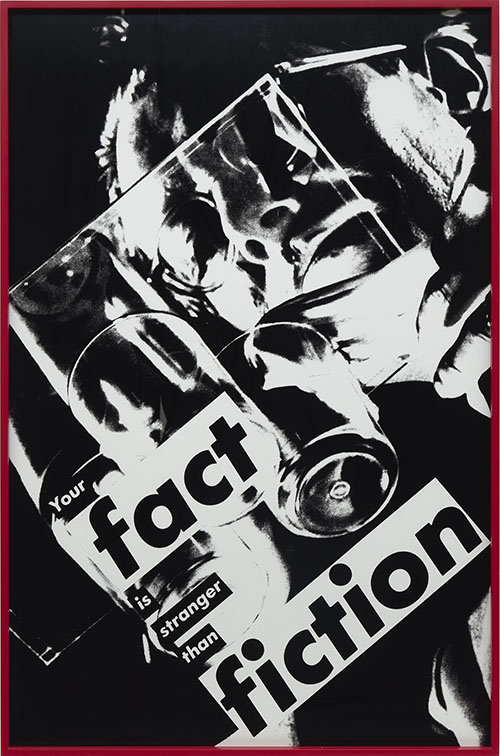

In many cases, an individual’s innate abilities seem to have drawn them to a particular kind of job. Later, making art drew on those same abilities and learned skills. “Media and Advertising” naturally includes works by Andy Warhol and Barbara Kruger, both of whom directly transferred strategies learned from the years they spent creating desire for products. Similarly, James Rosenquist, also represented here, worked as a sign and billboard painter before turning to his studio career. There is also a mesmerizing video and photo installation by Gretchen Bender, whose work deserves renewed attention outside of the specific context of the Pictures Generation. An early adopter of video, one of her day jobs included creating the barrage of images used as the title sequence for America’s Most Wanted and influential early music videos.

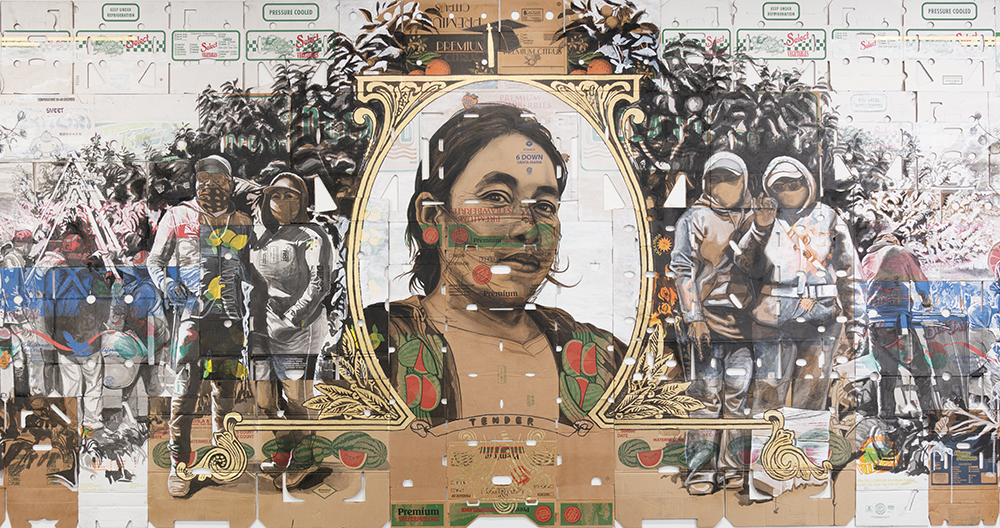

Some of the most compelling works in the exhibition appear in “Service Industry.” The most prominent is Narsiso Martinez’ immense painting Legal Tender (2022). Using charcoal, ink, metal leaf and gouache on flattened cardboard boxes, Martinez—who funded both college and graduate school doing agricultural labor– uses the format of a gigantic dollar bill to comment on the difficult, poorly paid and largely invisible work done by immigrant fruit and vegetable pickers. In the oval cartouche in the center, a young woman looks directly at us, her face radiating strength and calm determination. Several other workers, all acknowledged by name on the wall label, are portrayed throughout the work’s complex composition.

But something about Tom Kiefer’s photographs of decorative arrangements of objects from the US/Mexico border, where he took a part-time position as a janitor, feels uncomfortable. The wall label tells us he intended to create an archive of the American dream, but these water bottles swaddled in scraps of cloth and well-used billfolds—were they discarded, confiscated or, more sadly, once possessed by those who didn’t survive?

Julia Scher’s stint as a janitor for a gym and, later, her experience installing security systems for women clients also results in something that creates some discomfort, but in a good way. Learning the background information seems crucial to fully appreciating her strangely mesmerizing installation of pink surveillance gear and two uniforms. These pieces, dating from between 20 and 30 years ago, seem both quaint (elements include a camcorder) and entirely prescient.

Near Scher’s work is an installation of ten of Allan McCollum’s plaster surrogates – a collection of content-free, monochromatic “pictures” of varying sizes arrayed on a wall salon-style. Apparently, he worked at LAX in meal service for two years. Are these here because they resemble wrapped trays of inedible food? Did the experience of handling a multitude of similar objects inspire him to make his own exemplars? The wall-label assertion, that the surrogates question conventional hierarchies of labor, isn’t convincing.

The “Design and Fashion” category seems to be a catch-all. It is fascinating to learn that Jeffrey Gibson was so successful as a display designer for Ikea that the company wanted him to move to Malmö—which he almost did. Instead, he became a fantastically successful artist and the US representative at this year’s Venice Biennale. Three of his complex garments, hung theatrically on a long pole across the gallery space against a dazzling cobalt blue wall, reveal Gibson’s considerable skills with both design and fashion.

Working in his mother’s hair salon could be seen as making Mark Bradford’s early work fashion-adjacent. Two abstract compositions described as “mixed media” incorporate the rectangles of paper used to wrap hair ends, which the artist used to create many exquisite, grid-based abstractions. Richard Artschwager also seems like a smart inclusion here, but to say that the artist’s sculptures “bear uncanny resemblances to furniture” seems to miss the whole point of this aspect of his work, which is that they are simultaneously furniture, sculpture and image. The artist’s background as a cabinetmaker and designer of a wide variety of useful pieces equipped him to make endless insider jokes about the intersection between functionality and appearance. (McCollum’s work actually might have made more sense here.)

“Caregivers” includes a mother, a nurse and two nannies. Vivian Maier, represented with some of the earliest works in the show, became well-known posthumously for her extraordinary street photographs. That she was a nanny and also a perceptive and talented photographer can’t be denied, but the impact of caregiving on that work is slightly opaque. In contrast, Beverly Hills nanny Jay Lynn Gomez found her artistic voice squarely within her experience of being “the help” in wealthy households. Having noticed that magazine spreads featuring homes like the ones where she worked never showed the many workers essential to their upkeep, she painted in the workers.

Lenka Clayton pioneered a new wave of mothers who are artists and are not afraid to declare that they are both. Becoming a parent provided the framework for her self-declared Artist Residency in Motherhood at her home in Pittsburgh, where she has engaged in serious yet often funny ways with her dual roles. In 63 Objects Taken from My Son’s Mouth (2011-12), Clayton scrupulously collected and cataloged everything her toddler son managed to shove into his mouth until he knew better. She presents them in an elegant grid, recalling both display strategies used in museums of anthropology and by artists such as Mark Dion.

The final section, “Finance, Tech and Law,” seemed the least compelling, due, perhaps, to a combination of exhaustion and the seemingly pointless presence of Jeff Koons’ stainless steel bust, Louis the 14th (1986). Jim Campbell’s piece from 2011, Exploded View (Commuters) is, as always, both graceful and mysterious. Campbell’s background in tech is neither secret nor unacknowledged, and the work is no less compelling for it. That Koons was once a commodities trader is also well-known, but not significant to his development as an artist — the man could sell Christmas trees in January. He also worked at the membership desk at MOMA, a job at which he apparently excelled. But the Wall Street job? He took it to fund his art career until the art could sustain itself.

There was a time — not so long ago, in fact — when art historians’ overemphasis on artists’ biographies meant that the actual formal content of work was often set aside in favor of stories about love affairs, early death, rivalry, etc. The problematic effects of such fairy tales, particularly when considering the careers of women and artists of color, eventually caused Roberts’ discipline to swing radically away from any such considerations and towards the situation she describes: an airless environment in which only the characteristics of the work were considered, not all the messy but sometimes incredibly productive life around it. Criticism itself, when it followed into the same kind of formalist vacuum, came uncomfortably close to institutionalized racism/sexism/ageism.

Still, those stories about bad marriages or tragic deaths can be a distraction for art historians. It is easy to understand the desire to not read too much into the work based on what someone is (ethnicity, gender/orientation, nationality, religion) or does (employment, in all its forms). Thank goodness sociologists, anthropologists, art writers and journalists have all continued to think and write about questions pertaining to real life and its demands.

If art history is late to the party, at least it’s here now. Let’s talk about those day jobs, when they are relevant, and about parenting and all the other difficult, interesting parts of life. Sometimes, they make for the best art.

# # #

“Day Jobs” @ Cantor Arts Center through July 21, 2024

Notes:

- “I remember how stunned I was to learn from LeWitt that he had worked as a receptionist and night watchman at the staff entrance of MoMA. It was there, behind the desk and in break rooms, that he met Robert Mangold, Dan Flavin, Sonja Severdija (later Flavin), Robert Ryman, and Lucy R. Lippard.” Veronica Roberts, catalog introduction, p.9.

About the author: Maria Porges is an artist and writer who lives and works in Oakland. Since the late ‘80s, her critical writing has appeared in many publications, including Artforum, Art in America, Sculpture, American Craft, the New York Times Book Review and many now-defunct sites or magazines. She is the author of more than 125 exhibition catalog essays and Some Thoughts on Art and Work (Wolfman Books, 2020), and a professor at California College of the Arts.

WOW! Thanks so much!

Great piece Maria– Thank you.

And yes to:

Thank goodness art writers and journalists have all continued to think and write about questions pertaining to real life and its demands.

Keep it up!

What a well-written and to-the-point review. Thanks!

Bravo Maria, so well written and described!

Thanks

Beautifully considered and well constructed review!

Thank you, Maria Porges and Square Cylinder. I saw the show but didn’t have time to really take it all in. I’ll have to go back.