by David M. Roth

For most of his 30-year career, Rodney Ewing has examined Black American life in multi-media works that fuse his history with that of those who’ve come before. In his current exhibition, When We Move: A View of Technology through a Black Lens, he takes a big leap forward, conjuring a future in which Black people seize control of technology and turn it toward humanistic ends. In this endeavor, inspired by a treatise on that subject by Amiri Baraka, he’s joined by Nyame Brown, a San Francisco artist who shares a similar Afro-Futurist orientation calling for liberation. (The works here were selected from a prior exhibition at Santa Clara University curated by Pancho Jiménez.)

Ewing’s works lean less on technological fixes than on flights of imagination whose origins seem to rest more in late 19th and early 20th-century spiritualism than with anything invented in Silicon Valley. I say this because machines barely figure in any of his pictures; what we see mainly are Black figures hurtling through space, projecting thoughts or telepathically communicating – metaphysical possibilities long ago espoused by everyone from Madame Blavatsky and P.D. Ospensky to Timothy Leary and Terrence McKenna.

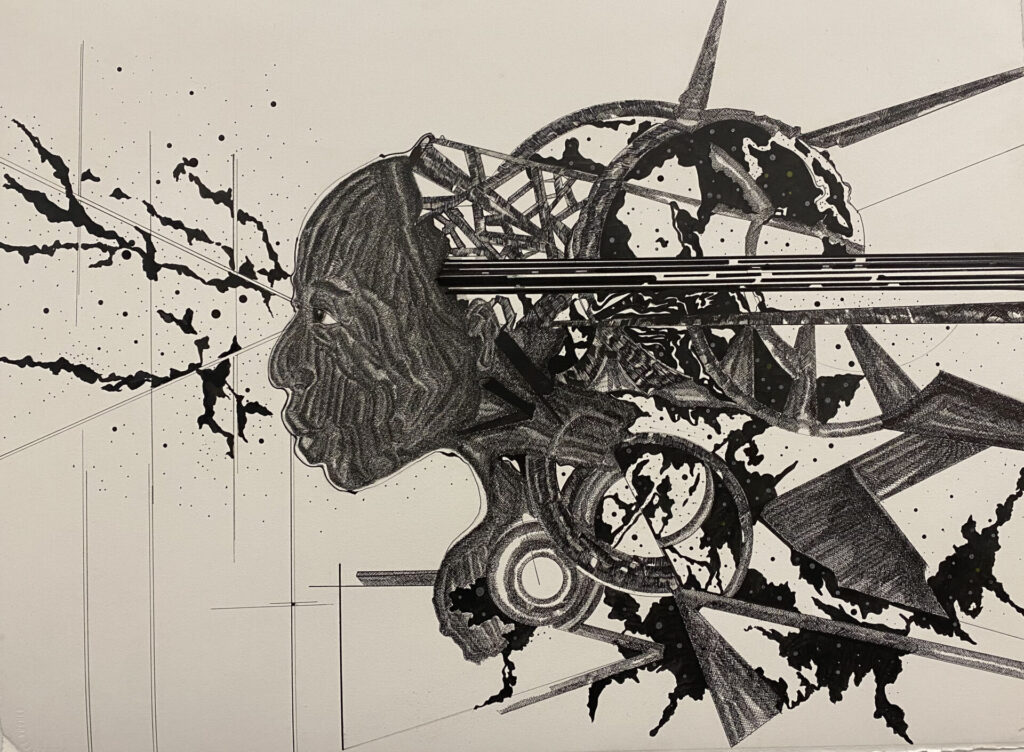

Visions of this sort could easily look cartoonish if Ewing were not such an exquisite draftsman. As a case in point, consider the male visage depicted in Study for Interstellar Travel, an ink-on-paper drawing measuring 22 x 30 inches. The shapes forming the face resemble embroidery, making for a dimensional

space whose patterns, meant to evoke braided hair, can just as easily be read as scarification since they cover both the face and neck. His rendering of the body is something else entirely. Shattered into geometric and glitchy shapes, it offers a snapshot of what teleportation might look like if captured in transit and propelled by a visible force field.

A companion piece, Study for Mass Communication, operates similarly. It shows a face “exhaling” an urban skyline, drawn as a series of vertical lines resembling those generated by an electrocardiogram. Call and Response, a 40 x 60-inch drawing, feels, with its haloed heads connected by slender tendrils, like a medieval portrait, only in this, the saints are Black men swathed in African textiles. Solar Return, the only drawing of Ewing’s that overtly references technology, shows a figure gesturing toward a group of schematic drawings labeled “Diagram of Lunar Module,” a juxtaposition that reminded me of Stoned Moon, the collage series Robert Rauschenberg made after watching the Apollo 11 launch in 1969.

Of the four works Brown has on view, the most compelling is Calling from Inside the Black House: How’s Yo Mama?, a 48 x 96-inch ink drawing that shows a male figure luxuriating in a well-appointed home finished in zebra-skin patterns. He sits in a recliner, coffee cup in one hand, remote control device in the other, smiling at an image displayed on a floating (transparent) monitor. Around him lay futuristic toys and African artifacts. On the walls, we see framed pictures, one of which is a reproduction of that famous photo of

Huey P. Newton sitting in a high-back wicker chair, armed to the teeth. The other half of the scene is comprised of cutout shapes of African diaspora nations. You needn’t be a genius to connect the dots: Newton’s vision of a liberated black populace joins that of Afro-Futurists like Sun Ra, who envisioned Black people migrating to another planet, freed from racism, capitalism, imperialism, colonialism and all other isms that have kept Black people down. A waveform representing an audio signal connects the two sides of the drawing, linking past to present, all in an appealing Afro-centric style. It’s a place anyone would want to dwell.

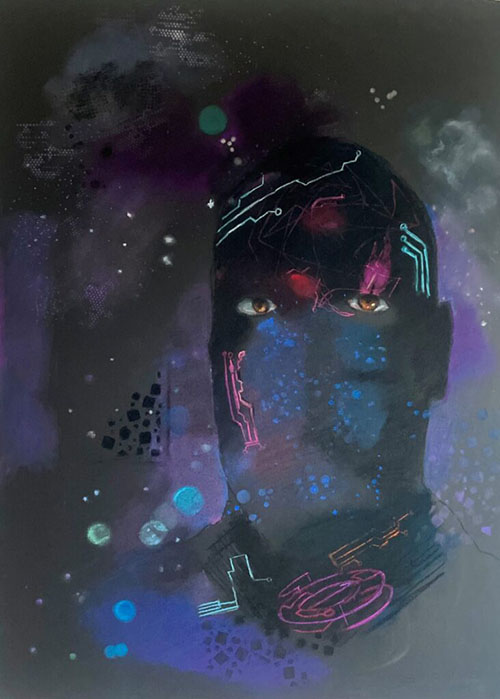

Two other pieces by Brown, both pastel drawings, point in the opposite direction, toward darkness and conflict. One shows a spectral face submerged in purple-tinged blackness; the other takes place on a starship, where two figures appear poised to clash. My only thought: We need to see more of Brown to assess his approach.

If there’s a problem with this show – and there is – it’s not about content or execution; it’s the artists’ decision to link their efforts to Baraka’s essay, Technology & Ethos, Vol. 2 Book of Life. The text, written in 1969, states the obvious: that technologies reflect the value of their creators and that those values ought to be spiritually oriented. Problem is, control of said technologies now rests with right-wing billionaires whose interests don’t align with anyone’s, save those of investors and tyrants. That said, the exhibition doesn’t rest all that heavily on technology. It’s powered by fervid mystical imagination – something Silicon Valley’s overlords have yet to control or co-opt. Will that be enough to throw off the shackles that bind us? I want to think so, but I’m quickly losing hope as we race toward a dystopian future where the off-ramps are increasingly blocked.

# # #

“When We Move: A View of Technology through a Black Lens”: Rodney Ewing and Nayme Brown @ Rena Bransten Gallery through June 29, 2024. The artists and the curator will converse at the gallery on June 1 at 4 pm.

About the author: David M. Roth is the editor, publisher and founder of Squarecylinder, where, since 2009, he has published over 400 reviews of Bay Area exhibitions. He was previously a contributor to Artweek and Art Ltd. and senior editor for art and culture at the Sacramento News & Review.