|

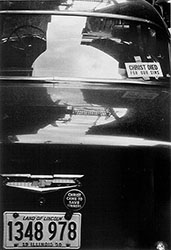

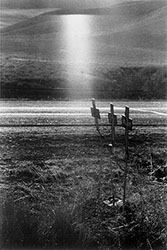

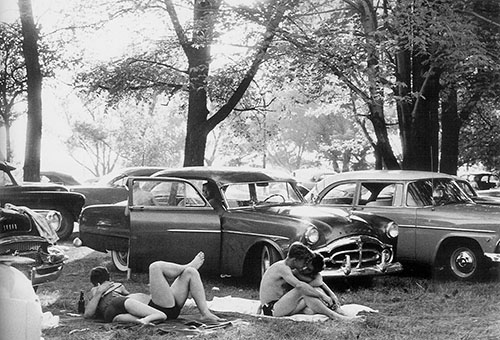

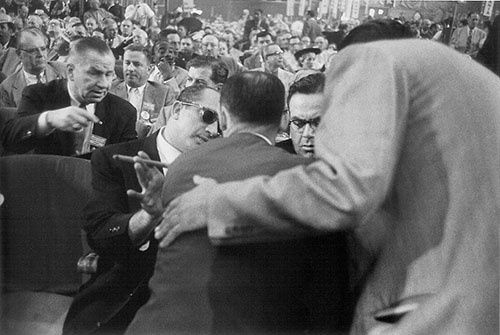

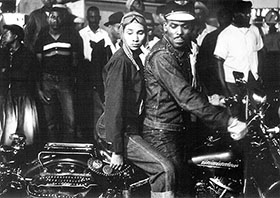

In the early and middle years of the 20th century, many photographers crisscrossed the American outback in search of the national character. None, however, delivered a portrait that came even close in force to the rough, poetic, critical vision that Frank laid out in “The Americans”. First published in France in 1958 and then released in the U.S. by Grove Press in 1960, its 83 grainy, loosely composed B&W images exposed the fissures in American life that WWII had only temporarily paved over. In the course of a two-year, 10,000-mile road trip begun in 1955 with a Guggenheim grant, Frank cast a cold, yet compassionate, eye on racism, economic inequality and consumerism. His view, as revealed through a self-selected prism of cars, bars and lunch counters, religious symbols, politicians and factory workers rubbed many Americans the wrong way because it did not reflect their gleaming self-image.

Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans and others had, of course, undertaken similar journeys under the auspices of the WPA. But what made Frank revolutionary was how he undermined “straight photography” with a bold, highly subjective approach that, over time, helped knock the wind out of “objective” reportage. In the history of photography, his work arrived at a critical juncture: when journalism was just beginning to cross over into art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frank stood his ground, and by the end of the decade he was universally hailed (and widely imitated) as legions of followers continued to push street photography deeper and deeper into the realm of fine art. For proof, one need only look at the work of artists like Garry Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz, Danny Lyon, Lee Friedlander, Joel Sternfeld and Stephen Shore to measure Frank’s influence.

As Frank explained: “I am always looking outside, trying to look inside, trying to say something that is true. But maybe nothing is really true. Except what’s out there. And what’s out there is constantly changing.”