For the past two decades, Nigel Poor has collected and organized human detritus into photo-based mementos of various kinds. These conceptual, emotionally rich presentations range from clinically-lit studio photos of everyday objects to nostalgic “dioramas” of rotting organic matter to non-photographic works that stand as fully realized abstract "drawing".

|

Poor operates on the principle that the smallest, seemingly most mundane items are the very things that reveal the most about how we live and what we value. Poor, you could say, is a professional obsessive, a forensic artist who’s made a career out of highly focused hoarding. She is currently engaged in a multi-year project (Do You Have 30 Seconds and Can You Get Your Finger Dirty?) in which she has collected fingerprints from more than 8,000 friends and strangers and transformed them into images (some as tall as seven feet) that demonstrate, at a readable scale, the fact that the fingerprints are as varied as snowflakes. In another project (Hand Job) she photographed people’s hands in any gesture of their choice. She’s also “mapped” her own random thoughts in reaction to external stimuli (like radio broadcasts), and accumulated and photographed junk that she collects on daily walks. All pretty much represent her taxonomic approach.

|

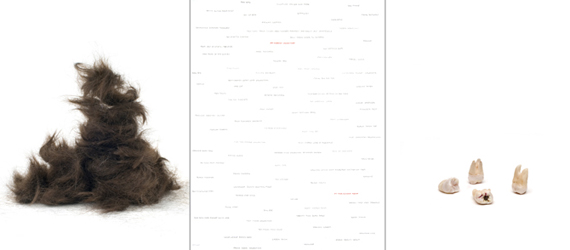

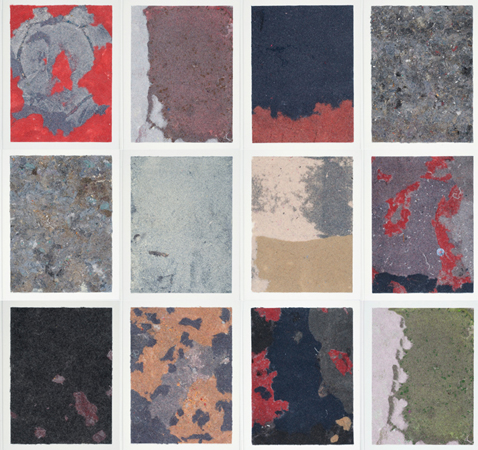

Here, in The Relative Value of Things, Poor takes a different approach: instead of collecting things, she discards once-valued personal effects and makes art objects out of stuff that has no apparent value: lint, hair and book pages. This upending of her normal working method and, of established ideas of value, yields some surprising results. In the case of the lint/hair/book works, the surprise is how beautiful and how painterly they are.

|

|

|

Arrayed across an entire wall in sizes ranging from 4” x 4” to 16” x 20”, they read like mash-ups of Mark Rothko and Clifford Still, but with specific associations: rag piles, multi-colored viscera, aerial views of the Earth, smeared pigment, honeycombs and, in the case of those spin-cycled books, grains of oatmeal with almost-legible text. The hair pieces read like gestural line drawings with an arc and flow dictated by the texture of the collected specimens; they range from lyrical to frenzied. Poor also makes drawings from Letterset type by inscribing the word “insect” 6,000 times in a shape that approximates the patterns of squashed bugs that accumulated on panels that the artist affixed to her moving car for that purpose.

Poor transforms these “value-less” materials into 36 unique book covers, displayed in grids of 12, with the Letterset pieces spelling out the sentence “Someday I will be as insignificant as a swarm of summer insects.”

|

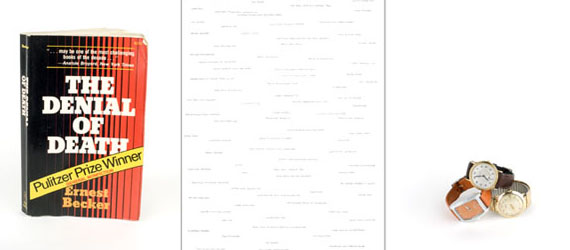

With that mantra in hand, Poor accepts Thoreau’s challenge to “Simplify, simplify, simplify.” She examined the stuff in her life, decided what to keep and what to throw out and then photographed all of the discarded items. Those pictures, which form the uniform content of each book, are displayed across one wall in 2-page panels. Among the discarded items are dead bugs, a wedding band, a bra, books on religion, the butt of a marijuana cigarette, the artist’s hair collection, wisdom teeth, watches, income records, Polaroids from a previous project and baby shoes. For viewers, it’s a voyeuristic journey that puts trash and treasure on equal footing – and leaves wide-open the question of how we value things, while making clear that she who dies with the most toys probably isn’t the winner.

Poor, however, doesn’t stop there. In an effort to engage the public in a similar self-cleansing ritual, she set up a website (www.nigelpoor-relativevalue.com) for people to report their purgative efforts. The results? Poor will use the postings (which can include both text and images) to create the final installment of The Relative Value of Things sometime after the website closes in May 2010. If the project catches hold, that is, if it goes global, one can easily imagine Poor as the chief curator of a pre-apocalyptic museum, creating displays that describe, in exacting detail, the excesses that make the human enterprise as poignant as it is doomed.

THE NIGEL POOR INTERVIEW

|

|

|

|

|

|

NP: I would like to end with two things from John Cage’s rules: Be happy whenever you can manage it. Enjoy yourself. It is later than you think. And here is the real kicker: Save everything. It may come in handy later!