|

What more is there to say about Carrie Mae Weems? Photographs and videos by Weems have been the focus of some fifty solo exhibitions, nationally and internationally, and too many group shows to count. Weems has presented her work to museum audiences in hundreds of artist talks and shared her practice with broad audiences in an episode of Art 21. Critics have covered her exhibitions for such prestigious publications as Art in America, Artforum, Aperture, American Art, the Washington Post and the New York Times. Respected scholars—including the curator Kathryn E. Delmez, and contributors to the current exhibition catalogue Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Robert Storr, and Deborah Willis–have offered their perspectives on Weems’s unique contributions to the contemporary arts. Most major American museums hold examples. Finally, the MacArthur Foundation just designated Weems a “genius.”

|

She uses various strategies to raise awareness of the extent to which culture—far from being the product of brilliant individuals–is collectively generated, often in humble settings like the kitchen. Tellingly, she counts the makers of Gees Bend quilts among her sources of inspiration. Weems studied folklore as a graduate student at UC Berkeley and remains passionately committed to popular art forms, oral histories, and the extra-institutional transmission of cultural identity. Some of her earliest exhibited work incorporates family pictures and oral histories recited in her resonant performer’s voice.

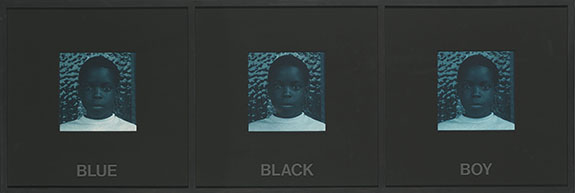

She began making photographs to create representational space “for women who look like me,” she has said time and time again in artist talks and interviews. “What do I want to see?” she asked herself as an undergrad at Cal Arts and then an MFA student at UC San Diego in the 1980s. Some of her very first published photographs appeared in Blatant Image (no.1, 1981) a radical feminist photography journal created, in the words of the editors, “to explore feminist values and expand the range of who is being seen.” These photographs–picturing women of all ages, body types, and heritages–contributed to the diversification of image culture, and thus became available as models for women. As participant observers, Weems and the other women photographers contributing to Blatant Image aimed to change the dynamics of cultural visibility, changing the ways women viewed themselves and were viewed by others.

.jpg) |

Very early in her career, Weems began to blur the distinction between participant and observer. In her well-known Kitchen Table Series, 1990, Weems acts as both the artist and the model. In this sequence of domestic mise-en-scenes, she represents herself, Carrie Mae Weems (cultural actor, director, and producer), and, at the same time personifies strong, black, modern womanhood generally.

|

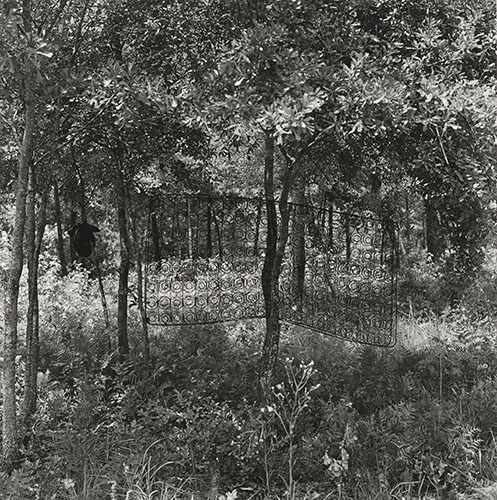

Even her landscapes may function this way, as portraits. They are marked by human hands and layered with lived experience. The Sea Islands Series, 1991-92, explores the “most African of American cultures” preserved by Gullah communities on islands off the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina without representing a single human inhabitant. Weems adopted a similar approach for two roughly contemporaneous series, Slave Coast, 1993, and Africa, 1993, where arresting photographic portraits of place (architectural structures, roads, pathways) combine with poetic texts to summon up the suppressed histories of men and women captured by slave traders and shipped like cargo across the

Atlantic. The images teach us about what Weems calls “the art of looking.” In the spaces between these haunted images of place and their accompanying text panels, untold stories resonate.

|