|

The Venice Biennial is celebrating its 120-year anniversary, but the awarding of the coveted Leone d’ Oro (Golden Lion) to the best presentation in the Biennial didn’t start until 1955. When the event began to feature an international curated exhibition in the Arsenale in 1999 and later, at the old Italian Pavilion (now called the either the Central Pavilion or the Biennial Pavilion, depending on who is in charge of “messaging” at Biennial HQ), two Golden Lions were given, one for best work within the curated portion and one for the best presentation in a national pavilion. Other awards are also given, but rarely do they garner any headlines outside of Italy. This year, the Golden Lions went to Adrian Piper for her presentation in the Arsenale portion of All of The World’s Futures, and to the Armenian Pavilion located in the Mekhitarist Monastery on the Island of San Lazzaro degli Armeni. My remark about Piper’s presentation can be found in the previous installment of this review, focusing on All of The World’s Futures, but, as is usually the case, both of these awards were recognitions of lifetime achievement status rather than the best presentations in the mega-exhibition that is Biennial 56.

“Lifetime achievement” might not exactly be the right words for the choice of the Armenian Pavilion, which gained attention because of its alignment with the centennial of the Armenian Genocide of 1915, a mass atrocity resulting in well over a million deaths, enacted by the then-extant Ottoman Empire and still vigorously denied by the current government of Turkey. Up until very recently, Armenia was part of the old Soviet Union — it is located between Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan — but became an independent republic in 1991. It

.jpg) |

was the first nation state to embrace Christianity as a state religion (in 303 C.E.), a point made relevant by the role played by the aforementioned monastery in printing and preserving sacred and historical Armenian texts. The exhibition features the projects of 14 artists working in what was called the Armenian Diaspora (Armenity/ Hayutioun, curated by Adelina Cüberyan v. Fürstenberg). The monastary itself was well worth the boat ride, a beautifully serene place built in 1717, on the site of what was once a medieval leper colony.

|

hung higgledy-piggledy on and about the walls, and on free-standing flat-screen video monitors and in vitrines full of miscellaneous objects that evoke a kind of magical universe of portentous omens as they might be imagined by precocious pre-teens. In point of fact, the pre-teens are featured as performers in the videos, which seem to be unscripted re-enactments of vaguely remembered ghost stories (about bees, fish and mirrors)—looking like home movie versions of the films that Matthew Barney has been making for the past two decades, minus the high-finish production values. Of course, to be completely fair, we should also recognize that Jonas has been doing performance oriented work with mytho-poetic purpose far longer than Barney, but the important point about performance is just that: it should perform rather than just take up space. An interesting side note is the fact that both Michelle Obama (with daughters) and Hillary Clinton were photo-op’d at the piece in mid-June, perhaps lured there by Roberta Smith’s fawning New York Times review proclaiming Jonas’ piece as a “triumph.” I beg to differ.

|

.jpg) |

For example, while perusing the vitrines, one notices graphic elements that point to something called “The Five Eyes Network,” which refers to the official collaboration of the intelligence services of the U.S., Great Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand—strongly suggesting how the later-named organizations can be seen doing the dirty work for the former, all working in concert to help the U.S. rebalance its geo-political portfolio in the direction of Asia, evidenced by the rush-to-ratification of the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. But there is more: Darchincourt seemed to have a special interest in book design, using his graphic stylings in publications aimed at introducing pre-teens to the fun hobby of code-breaking (with cute little turtles functioning as protagonists), and to ways of duping people into believing things that are not true. The coup de grace was one vitrine that contained replicas of props from the Terminator movies, which I am pretty sure that Darchincourt had nothing to do with. Nonetheless, Skynet has spoken, and every artist of the future-that-is-now has fallen into line.

|

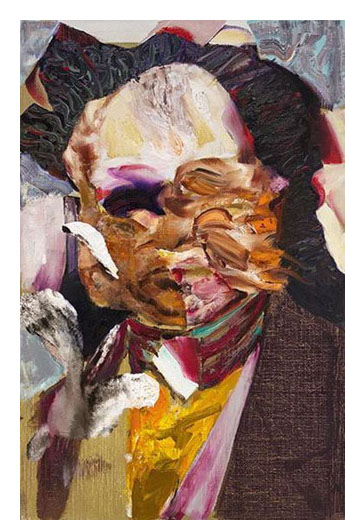

My Silver Lion goes to Adrian Ghenie, whose cycle of recent paintings titled Darwin’s Room was presented in the Romanian Pavilion. Ghenie’s paintings were the best to be found in any juncture of Biennial 56, which may sound like faint praise, because painting rarely figures prominently in any international biennial, including this one. This observation points to the chief bifurcation of today’s art world—there is the world of the art fairs, where painting, works on paper and photography reign supreme by virtue of the ways that today’s art shopper can partake of the kind of one-stop shopping, and thus, dispense with curatorial certification. And then there are the biennials, which are configured around large sculpture, installations and projections, in other words the kind of art that needs institutional spaces and their curators to come into being. The wisdom? There is nothing that curators love so much as art that confirms the continued need for curators. But back to Ghenie’s exhibition, which was extensive: over a dozen large works that bespoke perfect balance of range and focus, not to mention elements of abstraction and figuration. He paints in multiple registers and uses a multiplicity of tools for application, making his painting seem almost like collaborations between separate artists. But his works are unified by the interplay of layers of glistening color that flirt with muddiness and surprising jumps between involuted and extravoluted baroque gestures—a kind of Peter Paul Rubens meets Neo Rauch synthesis of exuberant, albeit measured, painterly affect.

|

|

The Korean pavilion (which is really the South Korean Pavilion) also played home to a cinematographic fantasy featuring a female character bounding around in an astronaut suit while variously configured light beams play about her, a celebration of technology that was both charming and frightening. The work was titled The Ways of Folding Space and Flying (2015), by Moon Kyungwon and Jeon Joonho, and was said to reflect Taoist notions of astral projection and time travel. I thought that the work’s sugary celebration of a fetishized idea of future technology was lacking insofar as a probing of the moral dilemma between the human and the post-human is concerned.

|

as Vanessa Beecroft, Peter Greenaway and William Kentridge are in the Italian Pavilion, which, even with their works, suffered from being far too polite. It is easy to see why the Italian Ministry of Cultural Assets and Tourism might see this as the proper path, especially in response to the so-called disastrous presentation of four years ago. That was the “art is not our thing” installation curated by Vittorio Sgarbi, which actually seized the holy grail of contemporary art that has slipped through the fingers of so many others—it was actually so bad that it was good. Sadly, the outrage provoked by Sgarbi’s exhibition seems to have created a backlash in the realm of official Italian art circles, for now the problem is that the organizers of the pavilion are now erring on the side of playing far too safe—no doubt in fear of having their budgets axed in the name of troika-mandated austerity. This was evidenced not only by this year’s Codice Italia, but also by the exhibition in the same space two years ago.

, 2009, oil on hemp cloth 194 x 260cm.jpg) |

Given the political news about Greek loan default and the fate of the Eurozone that was everywhere during the month of June, Ivan Grubanov’s entry in the Serbian pavilion titled United Dead Nations (2015) was compelling for its bittersweet timeliness. On the floor of the spacious room were nine piles of spent flags, some of which looked like they were drenched in blood. They represented nation states (or in one case, the Ottoman Empire) that for various reasons have ceased to exist during the past 120 years — the same time period that marks the history of the Venice Biennial. These political entities were given names on the walls adjacent to the flags, spelled out in block lettering to resemble the texts inscribed on grave markers. Actually, I think that more than nine have disappeared during that time (Rhodesia? Belgian Congo?), and I cannot help but think of what a countervailing exhibition pointing to the flags of newly minted nation states would look like; certainly, some of them would also be blood-stained.

|

painters of the Song Dynasty. If comparisons must be made, then they would have to include that most renegade of minimalist practitioners, Agnes Martin, or maybe the vogue for what was called “tough painting” during the early 1970. But even these seem a bit facile. However, as is the case with Martin’s work, the works of the Dansaekhwa artists do reflect a clear-eyed mindfulness that treats the works’ surface as a balanced synthesis of action and being that always seems simultaneously straight-forward and evanescent. Three of these painters (Kim Whanki [1913 to 1974], Ha Chong Hyun [b. 1935] and Park Seo Bo [b. 1931]) work on non-traditional surfaces such as hemp cloth, creating subtle configurations that subtly elaborate on the warp-and-woof of the work’s support. Others such as Kwon Young Woo work with Chinese ink on absorbent Korean paper, showing different ways of controlling the fluid edges of his applications in a way that echoes the “bone method” of the ancient literati painters, here modernized by way of organizing simple shapes in layered registers across the picture plane. Given the resurgence of abstract painting that has made its presence known during the past decade, it would seem to me that the work of these artists should receive a more serious look curatorial look, especially in the way that their work contrasts to the efforts of those painters that were included in the recent Forever Now exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art this past spring.

.jpg) |

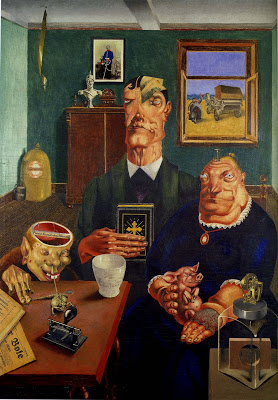

to 1919. In other words, it was what happened in Germany immediately after the First World War and as such, it makes for a very interesting comparison with Surrealism, which is what happened in France after that war. Of course, Dada happened in both places during the war (except that the French Dadists were all ducking military service in Zurich), but in Berlin Dadaists mixed in political elements in ways that its Franco-Swiss counterparts did not, and there was some clear overlap between the Berlin Dadists and the Neue Sachlichkeit artists. A good case in point could be found in the work of Georg Scholz, who was featured in the Musei Civici exhibition, although, rather unfortunately, not represented by his indisputable masterwork, the stupendous social satire titled Industrial Farm Family from 1920. There was a multi-colored lithograph of the same subject treated in the same way called Industrial Peasants, [1920], and that was wicked enough. Other works by Scholz included in the Museo Civici exhibition were almost as good, albeit less biting, for example, an ink and watercolor work from 1921 titled Work Defiles. There, he used a cast of pictorial characters such as pig-faced industrialists and war-wounded cripples to reveal the grotesque class discrepancies that were common features of the Weimar Period.

|