by David M. Roth

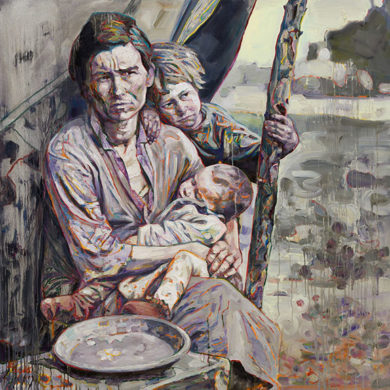

For the first time in a 30-year career Hung Liu has mounted a show of paintings that are not about Chinese history. The Oakland artist instead tackles the legacy of Dorothea Lange, the photographer whose pictures of post-Great Depression America, of people fleeing the Dustbowl for the West, long ago became iconic. For Liu this might seem like a departure. But it actually isn’t. Her paintings have always portrayed the downtrodden, and these, like so many she’s made of peasants, laborers, prostitutes, prisoners and famine victims, are very much of a piece with those she’s created from vintage Chinese photos.

The main difference here rests with paint handling. The virtuosic flourishes that have defined her output thus far — washes and drips interleaved with a heavy impasto – are in this exhibition somewhat attenuated, and that, in the context of Lange’s hardscrabble depictions of America’s dispossessed, feels about right. Liu’s treatment of two of Lange’s best-known images, Migrant Mother (1936) and White Angel Breadline, San Francisco (1933), illustrate. In these, her

Where Liu takes real liberties are with Lange’s lesser-known pictures. In these she uses blotchy, jagged cells to construct close-up portraits that may remind you of Chuck Close’s. Two that stand out are of African-Americans. Laborer: Farm Hand, based on Lange’s 1937 picture of a boy in Mississippi, transforms a sorrowful shot into a fragmented puzzle that far surpasses Lange’s in complexity and expressivity. The second, Mocking Bird, shows young woman in a bandana surrounded by bubbles, the effervescence coming from a blizzard of ovoid shapes that surround her face and body. Those, I’d wager, are inventions on Liu’s part, and they push an otherwise plaintive image into fantastical territory. Dreamcatcher, a picture of a girl on a narrow plank scooping water from a river is, I’d also speculate, an unremarkable scene in its original incarnation. Liu transforms it by appending multicolored bits of palette-knife-teased pigment to the top, to represent what I presume are blossoms dangling from a trestle. It’s as fine an example as any of how Liu — unlike Lange — consistently wrings transcendence from austerity.

Had Liu stuck to her early training in Socialist Realism and not gotten an American education that permitted and encouraged free expression, the paintings we see here would not, stylistically speaking, have been possible. That the best of them significantly depart from their sources lends double meaning to the title Promised Land, alluding to both the better life sought by the migrants Lange pictured, and to the storied career Liu achieved after arriving on these shores in 1984 with $20 and suitcase.

# # #

Hung Liu: “Promised Land” @ Rena Bransten through June 24, 2017.

About the author:

David M. Roth is the editor and publisher of Squarecylinder.