|

Talk about star-studded line-ups. This month, the Bay Area witnesses a confluence of art world supershows, the likes of which we rarely see opening all in the same month. They include a William T. Wiley career retrospective at the Berkeley Art Museum; a Morris Graves retrospective at Meridian Gallery; Robert Hudson’s first Bay Area show in nearly 20 years at Patricia Sweetow; and a display of new works by Richard Shaw at Braunstein/Quay.

Each is a major talent deserving serious reappraisal given the distance they’ve traveled. But it’s Wiley’s show that will most likely rise to the top of everyone’s must-see list, and for good reason.

|

Critic and poet John Yau zeros in even more closely on language: specifically, Wiley’s longstanding use of puns, malapropisms, homonyms and spoonerisms to wrap his works in an “archeological” skein of verbal contradictions. “Wiley records in great detail the wild buzz of thoughts haunting him,” Yau writes. “The motivating factor is his desire to map his state of consciousness … It’s as if he is talking to himself, and he has left his diary open to our examination.” Examine the evidence yourself and you’ll see how Wiley, using visual and verbal gymnastics, deflated the modernist notion of "artist as high priest” and replaced it with the decidedly countercultural ideal of “artist as wizard” – creating, in the process, an oeuvre that freely mixes the personal and the political in whatever media happens to be at hand.

Wiley certainly had his detractors. Hilton Kramer dubbed his art “Dude Ranch Dada,” denigrating his work for turning “the comic Western, with its parodies of heroism into a series of esthetic jokes on the relation of art to life, and has done so in a vocabulary that effectively removes the subject from its Eastern ‘intellectual’ associations.” As if deviation from modernist dogma was a crime! Wiley, of course, is having the last laugh, and not just because this show memorializes his achievements. The real measure of his vitality is his influence on artists working today. Wiley brought Dada and Surrealism – the art of the absurd and the unconscious — into the present, and he introduced, through his use of language, a savage wit that has yet to be equaled by any text-slinging artist in any medium.

No less formidable a personage, UC Berkeley Professor Emeritus Peter Selz, has organized the legacy of Morris Graves (1910-2001) into a succinct, but potent, show of 52 of the artist’s visionary paintings at Meridian Gallery – on the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth. The term visionary, which is often used to describe outsider art, really extends back much further, to well-known 19th century masters such as Odilon Redon, Albert Pinkham Ryder and William Blake and his disciples. Graves, for his part, carved out a reclusive, Thoreau-like existence in remote regions of the world, including the northern California coast where he culled spiritual insights from the gardens he cultivated. For more than 50 years until his death, Graves reigned as America’s leading mystic painter, rivaled only by his friend and fellow northwesterner Mark Tobey.

|

|

Born in Oregon, Graves transcended the limitations around him, both physically and mentally. He left his childhood home early to travel to Japan, and later melded the aesthetics of the Northwest school with the styles of Asia and European modernism. His images of birds, trees, flowers and animals range from the tormented to the sublime, and are characterized by a decidedly surrealist twist – modified and made original by his forays into Zen Buddhism and the theories of Carl Jung. As Graves wrote more than half a century ago, “The artists of Asia have a spiritually realized form within which we can detect the essence of man’s Being and Purpose, and from which we can draw clues to guide our journey from partial consciousness to full consciousness.”

|

Robert Hudson, Wiley’s close friend and an ally in the Funk movement that overtook Bay Area art in the ‘60s, demonstrates that despite an almost two-decade absence from the local scene, he can still thrill us. Of all the artists in his immediate orbit – a group that also included William Allan, Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner and George Herms – Hudson realized early on that his subject was perception; and no matter what form his work takes, whether sculpture, painting, ceramics or assemblage, Hudson always juggles form, weight, color and texture in ways that make viewers question the nature of what they see.

|

Lastly, we come to Richard Shaw, the undisputed king of trompe l’oeil ceramic sculpture. In the ‘60s he earned his bona fides studying with many of the Bay Area’s most finest artists — Hudson at the SF Art Institute and Wiley at UC Davis to name just two — and quickly joined their ranks. Using the temperamental material of glazed porcelain, Shaw makes true-to-life facsimiles of everyday objects: paint cans, playing cards, books, cigar boxes, pencils, letters, cheese rounds, branches and logs, saucers, tools, beer bottles, object-laden figures and table-top set pieces that appear to be built from studio detritus – but are really clever fakes, made “real” by the application of photo-offset decals that replicate product labels and illusionistic space. Legions of viewers (and even a few critics) have viewed Shaw’s works and come away wondering if they’ve just discovered an unseen side of Joseph Cornell.

–DAVID M. ROTH

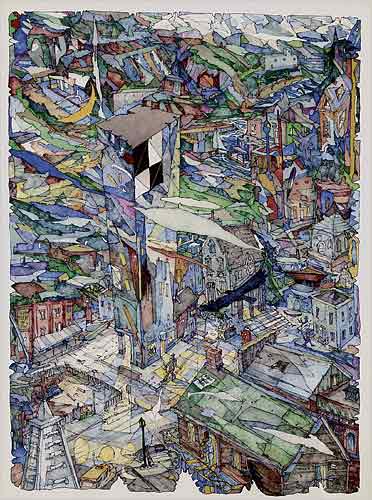

Cover image: William Wiley: (Detail) Your Own Blush and Flood 1982, watercolor on paper, 22 x 30 inches

William T. Wiley: What’s it all Mean? @ Berkeley Art Museum through July 18, 2010

The Visionary Art of Morris Graves @ Meridian Gallery through May 15, 2010

Robert Hudson: Sculpture & Drawing @ Patricia Sweetow through May 15, 2010

Richard Shaw: New Works @ Braunstein/Quay through April 17, 2010

I was “visually exhausted” after viewing the Wiley show…just fantastic! I’m looking forward to seeing the other exhibits listed here. Nice job on the site.

Just a marvelous show at Meridian – excellent curating, showing the best of Morris Graves’ work. A must-see show.

David,

These are insightful reviews that make our regional art inviting and available!

What a great article, I can’t wait to see the shows!

David, thank you for bringing the Morris Graves show to my attention. I’ve had the great pleasure of presenting his work in several exhibitions over the years. Morris was a great mentor as I struggled to find my voice as an artist, impressing upon me that the source of true art is from within. This is a must-see show!