by Bridget Quinn

Some years ago, I took a workshop on humor writing with a New Yorker contributor. When it was my turn to introduce myself, I mentioned being an art critic (funny!) and that I’d brought my special humor notebook for class notes, a bound journal with big shiny letters that read: FEMINIST. The instructor chuckled (whew), but a woman near me rolled her eyes and said, dripping with pity, “Nobody thinks feminists are funny.” Oh! I had no idea.

No idea except that I’d been hearing it my entire life. From Rush Limbaugh’s decades-long obsession with supposedly humorless “feminazis” to set-your-clock-by yearly think pieces on women’s humor (or lack thereof) in Vanity Fair (“Why Women Aren’t Funny”), Psychology Today (“Is It Misogynistic to Not Find Women Funny?”) and The New Yorker itself (“Women Just Aren’t Funny”). And yet, of course, I call bullshit. And, so have many women artists.

Probably most visible today are the Guerrilla Girls, still poking fun at the patriarchy more than three decades after their founding in the mid-1980s. But feminist art has a long history of humor. Think of Méret Oppenheim’s My Nurse from the 1930s, where a woman’s white heels are trussed up like a turkey and displayed on a silver platter. Is it such a big leap from there to Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party in the 1970s, with labia portraits as dinner plates? Maybe we should acknowledge that Chicago’s best-known work is pretty funny, and that’s ok. That humor is entirely appropriate to high art. Maybe especially feminist art.

She Laughs Back: Feminist Wit In 1970s Bay Area Art, currently on view at the University Library Gallery, Sacramento State University, seeks to underscore the vital current of humor in Bay Area feminist art of “the long 1970s.” If the venue sounds modest, the scope is not. The exhibition, organized by Sac State Professor Elaine O’Brien, features nearly 100 artworks by 19 artists. Because there’s so much erasure in the history of art around women artists, I think it’s important to recognize those in the show by name: Suzanne Adan, Dori Atlantis, Olive Ayhens, Viola Frey, Lorraine García-Nakata, Kathy Goodell, Lori Greenleaf, Vicki Hall, Elaine Gay Jarvis, Roz Joseph, Jean LaMarr, Judith Linhares, Yolanda López, Joan Moment, Donna Mossholder, Gladys Nilsson, Trina Robbins, M. Louise Stanley and Nancy Youdelman. Notably, Atlantis and Youdelman’s contributions include their work with fellow students alongside Judy Chicago in the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno, the first feminist art program in the United States, or anywhere. Atlantis’ iconic photograph of the CUNT CHEERLEADERS (1971), included in the show, situates California as central to 1970s feminist art, and quite possibly its epicenter.

Maybe the catalog – which was unavailable when I visited – reveals more than the wall labels about California’s importance in the global development of feminist art. However, the exhibit’s introductory wall text does convey the importance of the Bay Area to liberation movements generally: “From the mid-1960s through the early 1980s, the Bay Area was at the center and origin of anti-war, free speech, Black Power, Red Power, Chicano, Third World, and gay and women’s liberation movements that challenged traditional belief systems and structures of power.” With all that in mind, while including Native, Chicana, Asian-American and LGBTQ art and artists, Black feminist work seems strikingly absent. It feels like a missed opportunity, considering that Betye Saar’s Liberation of Aunt Jemima was created in 1972 for a show at the Rainbow Sign in Berkeley.

That said, She Laughs Back has far more hits than misses. Clear standouts include M. Louise Stanley, with one of the first paintings as you enter the show, The Mystic Muse and the Bums Who Sleep on the Golf Course Behind the Oakland Cemetery from 1970. It’s a vibrant watercolor of a levitating female nude surrounded by men that came out of Stanley meeting with College of Arts and Crafts friends in the Mountain View Cemetery behind the school to paint, where the point was to break away from abstraction and make “Bad Art.” It’s reminiscent of any number of renditions of the Old Testament story of Susannah and the Elders in art history — a nude woman gawked at by leering men. But in this case, the nude is electric in her naked power, a filament of light in the dark, surrounded by clown-faced onlookers.

Such pinballing off the history of art constitutes some of the strongest work in She Laughs Back, when the artists comment, with droll awareness, on its whole shaky apparatus. Stanley’s Diana Resting (1979), a revisioning of Baroque or Rococo scenes of the huntress and her nymphs, is another example. Only here, there are no men in sight, and the delight of these forest nudes resides mainly in their faithful dog companions. It’s beautiful to behold: tender, sweet, bold, and, yes, a little funny (certainly fun). The same holds for Rust’s Wedding, or The Uninvited Guest (1972), an autobiographical scene depicting Stanley’s sister’s wedding in Humboldt County where a Bruegel-like feeling of village peasantry, recast in 1970s NorCal, prevails. This village, however, includes a giant grasshopper and a dancing circle of angels that the wall label says “are borrowed from Piero della Francesca” — and also very likely from Botticelli’s The Mystical Nativity (c. 1500), which was recently on view at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco.

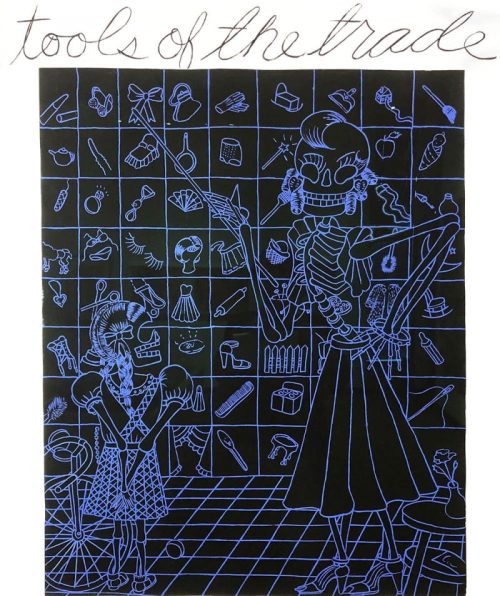

Similarly, Judith Linhares draws from Mexican art and culture in Tools of the Trade (1978) with female skeletons that immediately bring to mind Jose Guadalupe Posada’s famous La Calavera Catrina (1913). The adult and possibly the mother — who we identify as female from her skirt, bangle and heart-shaped earrings –- appears to instruct a little girl (a skeleton in pigtails and pinafore) in the ways of womanhood. The mother points to a Loteria-like image grid that includes a wedding ring and lipstick, a bow and brassiere, dustpans and a rolling pin – tools, in other words, for assembling a “real woman.”

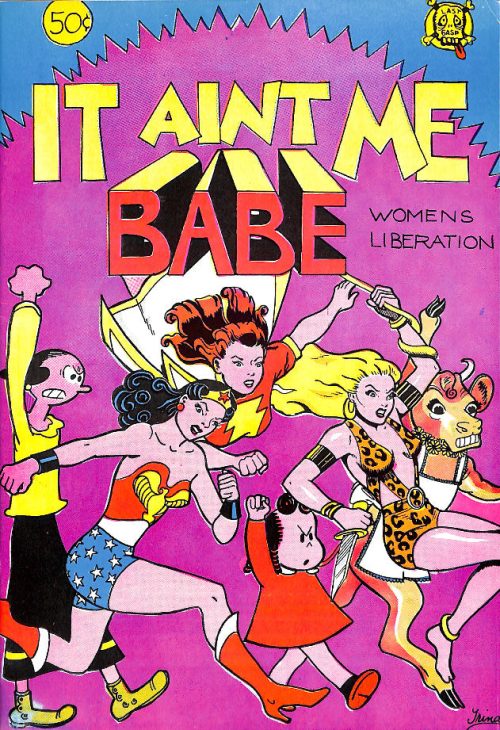

Yolanda López’s Tableaux Vivant (1978) also alludes to Mexican art in photographic self-portraits executed in the guise of the Virgin of Guadalupe. It’s the artist as universal mother, as Mexican deity and cultural icon – smiling in sneakers and running shorts. She is beautiful and badass, fun and powerful. Trina Robbins also invokes cultural icons, in this case American cartoons. Her cover for the underground comic It Ain’t Me Babe features Wonder Woman alongside Olive Oyl and Nancy giving power salutes. Pages of that work, on display in She Laughs Back, signal the need for a whole exhibition dedicated to her career.

Likewise, paintings from Joan Moment offer a tantalizing look at an important artist ripe for a career retrospective. In Eve and the Serpent (1974), a canvas that figured prominently in her 1974 solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum, she references a familiar figure from art history, the universal temptress, Eve. Moment recasts her as a strong solo figure, sans Adam, with her snake companion in paradise.

While Eve and the Serpent reflects on a long tradition in Western art history, Moment’s Condom Relief Series No. 1, 1971 (refabricated in 1993) brilliantly responds to and riffs on art world practices of the 1970s, placing 96 condoms in a large grid on gauze, so that figure and ground share the same pale, slightly translucent golden color. It immediately calls up many associations of its time, from Eva Hesse and Sol LeWitt to Agnes Martin and Robert Ryman. This utilization of the formal language of Minimalism and the modernist grid — in condoms — is an ideal marriage of form and content. It celebrates and mocks the formalist obsession with the grid, purity and formal elegance with earthy humor and maybe a little shot (if I may) at the masculine pretensions of much minimalist art and art criticism. It’s brilliant, fun, funny, and, just as importantly, gorgeous.

Significantly, Condom Relief Series No. 1 is the one piece in She Laughs Back where I repeatedly heard viewers laugh out loud on seeing it. That said, it is an exhibition of many pleasures, filled with art and artists well worth revisiting, covering a time that needs not just remembering but reviving. I have faith that might happen. I discovered a twentieth artist on my way out when I grabbed a great zine by CSUS student Lena Sakkab that makes clear feminism and funny are still alive. Thank goddess.

# # #

“She Laughs Back: Feminist Wit In 1970s Bay Area Art” @ University Library Gallery, Sacramento State University through April 13, 2024.

Bridget Quinn is the author of the books Broad Strokes and She Votes, both about women’s history and art. She’s a regular contributor to Hyperallergic and a sought-after speaker on women and art. Her next book, Portrait of a Woman: Art, Rivalry & Revolution in the Life Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, is forthcoming in April 2024 from Chronicle Books.

Lulu rules the paintings. Always great, now immortal!

Hi Frank,

Are you sure you don’t mean immoral? Not immortal!

One of the Artpolice comics is featured in a vitrine.

‘Stalking the Southern Bell’ 1979 vol 3, No 1

xxx lulu

M. Louise Stanley (LuLu) you are one the great artists of our time.

Thank you Bridget. It is wonderful to be part of this show and in the company of so many fabulous artists. Funny isn’t the end of it!