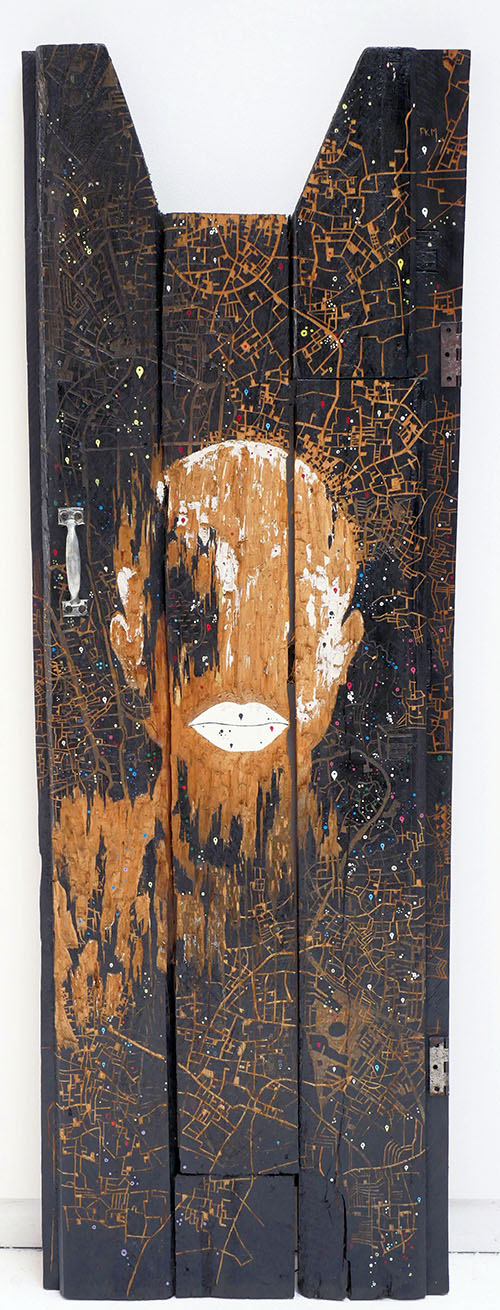

59 x 20 x 2 inches

by Gabrielle Selz

Positioned on a pedestal against a wall, a single door stands erect, its surface etched to reveal a striking visage. Only the contours of the head, with white-painted lips and ears, are discernible. The remaining features, obscured by gouged marks, appear flattened, like a silhouette. Surrounding the head, sprouting from the skull, like wild entwined hair, and extending down from the neck and shoulders like a network of veins, roads branch and twist into a map of an unknown city. The piece is called Autoportrait, one of many compelling works by Alexandre Kyungu Mwilambwe that explore themes of mobility, identity and the quest for freedom. They employ cartographic drawing to create imaginary spaces and objects rife with possibility. Mlango (The Door), the Congolese artist’s first solo exhibition in the US, features sculpted doors, drawings on paper and board, footstools and several wall-mounted sculptures made from salvaged rubber.

Born in Kinshasa in 1992, the artist studied at the Academy of Fine Arts and has quickly become one of the region’s rising young stars.

As architectural objects, doors are ubiquitous (the doorway to your home) and extraordinary (the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica, which opens only every 25 years). As structures, they offer protection and passage. As metaphors, they function as portals to new destinations. Artists from Willem de Kooning, who liked the size and dimensions of a door, to Jean-Michel Basquiat, who liked their dual-sided nature, have adopted it. Mwilambwe appears similarly inclined.

He embeds urban maps into doors, which he dissects, carves and perforates to form faces, holes and windows. The result is a kind of scarification that pays homage to the ancient (3600 BCE) tradition of creating raised scars on the body for adornment and tribal affiliation. As it happens, some of the most intricate designs in Africa have been found in Congo, Mwilambwe’s birthplace. By combining scarification and cartography on one surface, he questions the way colonizers have imposed borders on Africa and across the globe. He views both practices as constructs. One marks and distinguishes people and establishes identity; the other partitions and controls territory. The resulting objects give off a numinous presence, unburdened by artificial, manmade boundaries.

In 2020, Mwilambwe began working with old paper maps, embellishing the antiquated relics with scarification made of glue and mounds of wood dust. The results, seen in drawings like Nzoloko of Northwest Germany, read as elegant, mysterious hieroglyphic forms, suggesting migration patterns. Other, bolder works on panel, like those from the Scar Areas series, resemble aerial views of Nazca lines overlaid with graffiti painted in neon green.

In his most recent work, Mwilambwe repurposes car tire inner tubes, a product with an ignominious past. During Congo’s colonial era, King Leopold II of Belgium took possession of vast territories to exploit rubber for profit. His policies enslaved and killed some 10 million people, half the population. Mwilambwe stretches, slices and incises the material, creating intricate patterns with the slick viscosity of an oil spill and the delicate intricacy of lace embroidery. The resulting forms, which cast shadows onto gallery walls, resemble urban grids in some areas and spider webs in others. In The Scar in the Earth V, three figures emerge from the snarled netting of an urban jungle into an open expanse. A man and a woman exchange a flower while a solitary figure gazes off into the distance. It’s both haunting and uplifting, signaling an emergence from a tangled maze into a realm different than that of official maps that describe the landscape and tell us how to navigate it.

With that orientation, Mwilambwe joins his countryman, the sculptor Bodys Isek Kingelez, and a growing international cohort of contemporary artists (e.g., Lordy Rodriguez, Yin Xiuzhen, Alighiero Boetti, Juan Downey, Mona Hatoum, Val Britton, Audrey Tulimiero Welch, Matthew Picton) who’ve subverted the proscriptive character of maps to lay out their own vision of what the world might look like.

# # #

Alexandre Kyungu Mwilambwe: “Mlango (The Door)” @ Hosfelt Gallery through May 4, 2024.

About the author: Gabrielle Selz is an award-winning author. Her books include the first comprehensive biography of Sam Francis, Light on Fire and Unstill Life: Art and Love in the Age of Abstraction. Her essays and art reviews have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Hyperallergic, Art & Object, Art Papers, The Rumpus, and The Huffington Post, among others. She makes her home in Oakland, California.