Download: Robert Atkins on Frida in Film

The term biopic debuted on the pages of Variety—the entertainment industry daily—shortly after World War II. (The industry insider knew that in Variety slanguage “Leo & Ileana’s Love Story is boffo at the B.O.” meant, “Leo & Ileana’s Love Story is making big money at the box office.”) Universally understood now, biopic simply refers to a film that depicts the life of a politician, scientist, athlete, criminal, or artist—albeit the last only occasionally.

Selena, Elvis, Ray Charles, Freddie Mercury, Leonard Bernstein and Bob Marley have all been the subjects of recent biopics. Visual artists rarely receive such visibility. The last art-related film I recall enjoying—not a biopic, though–was Big Eyes (2014), the story of painter Margaret Keane’s big-eyed waifs and her ex-husband’s sleazy attempts to swindle her out of credit for them. (Along with Big Eyes, I Shot Andy Warhol (1996), the story of Valerie Solanas’ attempted assassination of the Prince of Pop, suggests that female criminality, at least, is cat nip to film producers.)

The professional inequality that puts artists behind musicians or politicians surely relates to the lack of cinematic appeal. In the popular imagination, artists like Jackson Pollock and Andy Warhol are often regarded as emblems of avant-garde charlatanism, an association dating back at least as far as 1913 when Theodore Roosevelt likened Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending A Staircase, No. 2 (1912), on view in the epochal Armory Show, as an “explosion in a shingle factory.”

Even so, the earliest biopics about artists were as reverential as those about other historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Graham Bell or Marie Curie. Blockbusters like The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), starring Charleton Heston as Michelangelo, and Lust for Life (1956), featuring Kirk Douglas as Vincent Van Gough, were based on best sellers by Irving Stone. Both trafficked in romantic cliches: the artist-genius and his struggle for artistic autonomy and the starving artist and his painful struggle for acceptance, respectively. Such tropes remain nearly as ubiquitous as those of rock musicians burning bright and dying young, invariably of drugs. (Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996), the rare bio-pic devoted to a contemporary artist, also treats its subject as a rock star.)

Even so, the earliest biopics about artists were as reverential as those about other historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln, Alexander Graham Bell or Marie Curie. Blockbusters like The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), starring Charleton Heston as Michelangelo, and Lust for Life (1956), featuring Kirk Douglas as Vincent Van Gough, were based on best sellers by Irving Stone. Both trafficked in romantic cliches: the artist-genius and his struggle for artistic autonomy and the starving artist and his painful struggle for acceptance, respectively. Such tropes remain nearly as ubiquitous as those of rock musicians burning bright and dying young, invariably of drugs. (Julian Schnabel’s Basquiat (1996), the rare bio-pic devoted to a contemporary artist, also treats its subject as a rock star.)

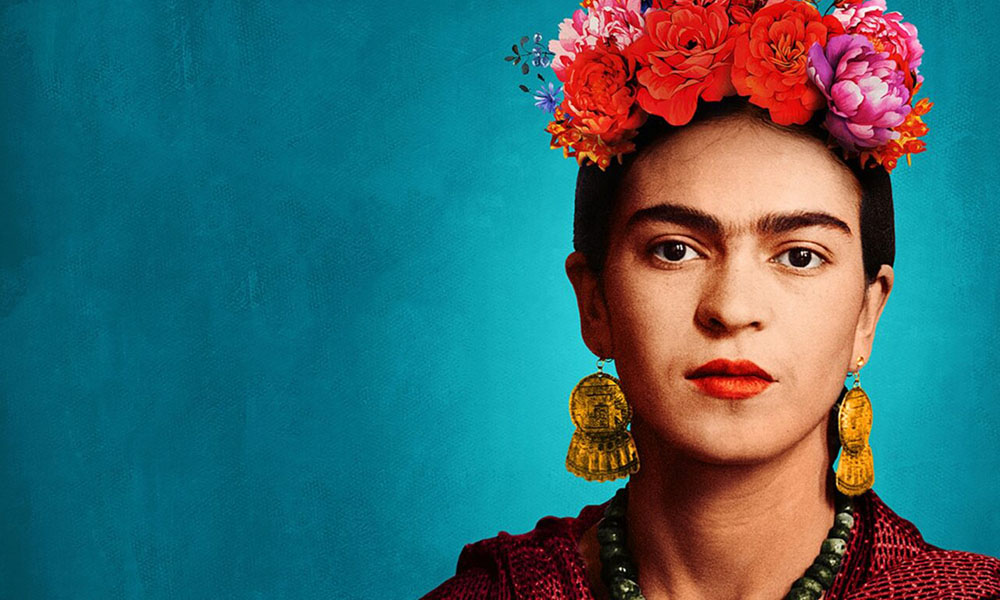

Not surprisingly, female artists have gotten short shrift. The exception is Frida Kahlo (1907-54), the iconic Mexican painter. A fiery figure, she led a life filled with drama. Victim of a crippling, near-fatal collision between a bus and a trolley car, she produced brilliant art that was underappreciated during her lifetime. She also possessed a wicked tongue, an expressive fashion sense, and an instantly identifiable unibrow. She was a passionate leftist and briefly a communist party member and was intimately involved with some of the most famous figures of her day. Diego Rivera was her husband; the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and the artist Isamu Noguchi were among her many lovers, male and female. Was there ever a more charismatic subject?

Starting nearly 30 years after her death and coincident with the publication of Hayden Herrera’s Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo (1983) and the completion of Roberto Guerra and Eila Hershon’s TV movie Frida Kahlo (1982), she has been the subject of more film and video productions than all other female artists combined. These include, whether in English or Spanish, at least two other TV biopics, three TV series and five film biopics, the most famous being Julie Taymor’s Frida (2002), starring a luminous Salma Hayek. The pace has picked up lately: Three new productions devoted to the surrealist painter were released during the past five years. Do we need another? The folks at MGM-Amazon, which released Carla Gutierrez’s Frida, apparently thought so—as do I. A nominee for a grand jury prize at Sundance, it is arguably among the finest films about an artist ever made.

What distinguishes it from previous films about artists—documentary or narrative–is what it is not. Without expert talking heads, it bears little resemblance to conventional documentaries that offer interpretation and judgment about a subject’s work. The expert we hear is mainly Kahlo herself, voiced by Fernanda Echevarria, speaking words from Kahlo’s interviews, letters, and a newly discovered diary found hidden in the bathroom of Casa Azul, her Mexico City residence. The words of Rivera and a few of Kahlo’s other friends, spoken by unseen voice-over actors, supplement her own.

The visuals are as intriguing as the cast of characters. Frida’s father, a photographer interested in the natural world, helped inspire Kahlo’s pre-med studies. His vocation helps account for the numerous childhood pictures, including those capturing her rebellious antipathy toward religion, a stance opposed to her mother’s “obsession” with religion that brought priests to the Kahlo household as Sunday dinner guests.

Every important moment of Frida’s life seems to have been documented in images. It is remarkable, for example, to see the apparatus her mother rigged for her to write or draw in bed after her near-fatal bus accident at age 18. News photos of the accident document the horrific scene — her companion on the bus recalls that when the column on which she was impaled was removed, Frida’s screams were so loud they drowned out the sound of the arriving ambulance. “I now inhabit a world of pain,” Frida says of the event that irrevocably altered her life. “At least Lady Death did not take me.” The year she spent in bed was the origin of her discovery of art as a means of personal expression. Remarkable portraits of her friends, which she sent to them, embodied the pain of isolation. “Do not forget me,” they seemed to (unnecessarily) utter.

Every important moment of Frida’s life seems to have been documented in images. It is remarkable, for example, to see the apparatus her mother rigged for her to write or draw in bed after her near-fatal bus accident at age 18. News photos of the accident document the horrific scene — her companion on the bus recalls that when the column on which she was impaled was removed, Frida’s screams were so loud they drowned out the sound of the arriving ambulance. “I now inhabit a world of pain,” Frida says of the event that irrevocably altered her life. “At least Lady Death did not take me.” The year she spent in bed was the origin of her discovery of art as a means of personal expression. Remarkable portraits of her friends, which she sent to them, embodied the pain of isolation. “Do not forget me,” they seemed to (unnecessarily) utter.

Even more remarkable are the films—some in color–of private and public events in Frida’s life. We see her welcoming the Trotskys to Mexico on the docks of Tampico and the openings of exhibitions she had in New York, at Julian Levy’s prestigious gallery, and in Mexico City and Paris. Her Paris show, haphazardly organized by surrealist impresario Andre Breton, featured her paintings in a gallery “contextualized” by what she called touristic “crap” from Mexican markets. When nothing sold, she quipped, “the rich [Parisian] bitches don’t want to buy anything,”

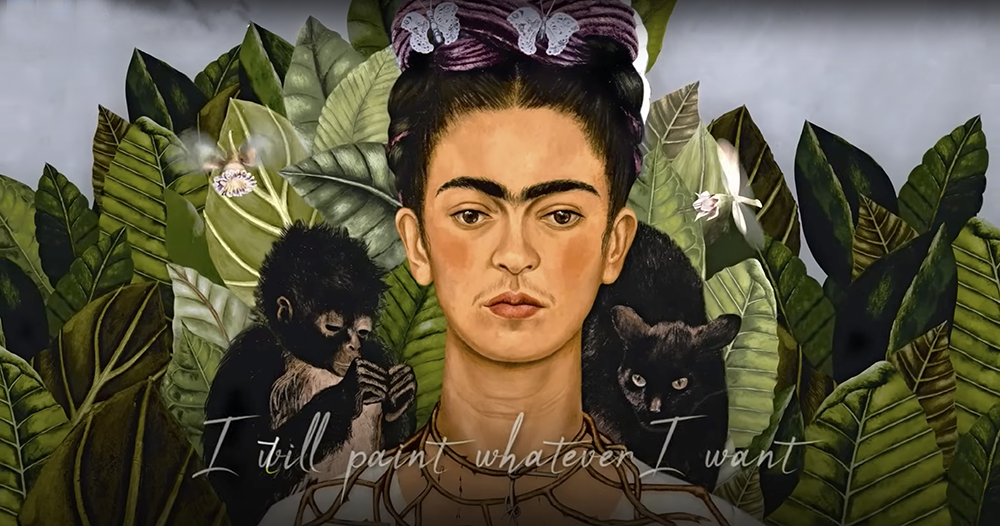

The film’s biggest visual surprise is the expressive animations created from the artist’s paintings and drawings. Through the efforts of an army of animators, internal organs writhe and throb, butterflies and birds twitter, the hair she cuts off her head floats lazily to the ground, the fetus of her miscarried child (she lost three), anchored to her body by an umbilical cord, sways against a heavenly sky; and waves break and re-form around faces in portraits. Normally, animations of this sort might be cloying and distracting; here, they’re riveting. They point to meaningful, easily missed details within a work.

Another improbably effective feature of the film is the character and eloquence of Kahlo’s words, often heard for the first time in film. They remind us that hers was an era of letter writing and of careful looking and clear communication. That Kahlo swore like a longshoreman, reflected her demand for unflinching honesty from herself and others.

Her most important conversations are, no surprise, with the brilliant leftist painter Diego Rivera. The celebrated muralist, who she met when she was just 21. is so tall and rotund that he dwarfs her. Paintings in hand, she summoned him from the scaffold on which he was working and a conversation ensues. He admires her canvases; she alludes to the spectacle of his womanizing. They marry a year later, in 1929.

Their ongoing dialogue fortifies them both, encompassing abstraction, the role of art in revolution, the nature of love and lust, and the identity of lovers they rarely hid from one another. The latter included Kahlo’s sister with whom Rivera was having an affair, and Leon Trotsky with whom Kahlo was carrying on similarly. Both could shut out the world with words, whether ecstatic, wounding or funny. He says, “You have a dog’s face.” She responds, “You have the face of a toad,” which becomes one of her nicknames for him. They’re both hedonists. He likens sex to pissing, and she believes that what is pleasurable is good, but only within her principled vision of the world.

She and Rivera moved to separate residences in 1935, divorced in 1939 and re-married a year later at his prompting, an arrangement that included a 50-50 division of household expenses. Their extended trips to the US, demanded by his commissions in California, New York and Detroit, exhausted her. She mourns her third miscarriage far from home and is unsure if Rivera wants a child. American capitalist society’s indifference to Depression-era disparities in wealth appalled her. (“Everything here is about appearances, but deep down it is a pile of shit.”) Despite Nelson Rockefeller’s destruction of his fresco for Rockefeller Center, Rivera remained fascinated by the U.S. and industrial modernity, a perspective she didn’t share. She received a prestigious professorship in 1943 but had to hold classes at home due to failing health. She spent her final decade in renewed political activism, painting, and coping with the unimaginable pain of seven operations and the amputation of a leg.

As for Kahlo’s brilliant and well-known art, it requires no comment from me. I quote Rivera’s astute and touching tribute, delivered at the opening of the only exhibition of her art in Mexico City held during her lifetime, at the Gallery Lola Alvarez Bravo. She attended on a bed rolled into the gallery from an ambulance. “I want to speak about Frida not as her husband but as an artist,” Rivera said. “I admire her. Her work is acid and tender… hard as steel…and fine as a butterfly’s wing. Loveable as a smile…cruel as the bitterness of life…I don’t believe that a woman has ever before put such agonized poetry on canvas.”

At Sundance, Frida was nominated for the Grand Jury Prize for documentary. In a hybrid age, such boundaries between genres are melting faster than the polar ice caps. In the case of Frida, the distinction between documentary and biopic rests largely on whether or not the actors playing their parts are seen onscreen. Put another way, Frida is to film what creative nonfiction is to fiction. Meaning, such distinctions are no longer relevant. I describe the film simply as an original and artful portrait of a great artist. It will, I hope, attract the boffo viewership it deserves.

# # #

“Frida” is streaming on fubo TV, Paramount +, Amazon Prime, Showtime, Apple TV, Google Play Movies and Vudu.

About the author: Robert Atkins is an art historian and writer working at the intersection of art and politics. A former staff columnist for the Village Voice, he has written for more than 100 publications throughout the world, ranging from the New York Times to Japanese Wired. He is the co-author, most recently, of Censoring Culture: Contemporary Threats to Free Expression and the ArtSpeak and ArtSpoke series of art guides. He has curated exhibitions at far-flung venues, including the São Paulo Biennal and New York’s New Museum and co-curated From Media to Metaphor, the first international traveling exhibition of AIDS art. A pioneer of online art and resource production, he is a fellow of Carnegie Mellon’s STUDIO for Creative Inquiry and a co-founder of Visual AIDS, the creator of Day Without Art and the Red Ribbon. He lives in the Southern California desert.