|

Now that the all-new, tripled-in-size Crocker Art Museum has opened, it’s hard to decide which aspects of this achievement are the most remarkable: the building itself, the art inside or the fact that the project actually materialized.

|

|

.jpg) |

The upstairs galleries of the expanded 125,000-square foot new wing are a labyrinthine maze of interconnected rooms: light-filled spaces that seem to flow one into the other, each revealing a different part of the Crocker collection. It’s a bad-news/good-news proposition. Much of what the museum inherited from its benefactor, Judge Edwin B. Crocker, just isn’t very good. On various buying sprees, the judge and his wife, Margaret, loaded up on Central European paintings that hang on the walls of one very opulent, very beautiful room in the original gallery. California Impressionists, a group that made negligible contributions, also occupy substantial space. To their credit, the Crockers amassed one of the world’s largest collections of Old Master drawings. Those, too, have a room of their own. More recently, the museum, which was already a major player in ceramics, acquired Sidney Swidler’s encyclopedic collection of 800 pieces. They roam from the merely functional to the utterly phantasmagorical and are documented in a 408-page catalog written by Associate Curator Diana Daniels.

|

Perhaps the most entertaining part of the museum, which I’ll call the “Early California Room”, is dominated on one wall by the high-kitsch dramas of Charles Christian Nahl (1818-1878), a failed prospector who earned his living painting commissions for San Francisco’s elite. His rose-tinted, Arabian Nights meets Rape of the Sabine Women depictions of virgins being pursued by lusting horsemen look like something straight out Cecille B. DeMille.

The really good news is that the Crocker, which bills itself as “the oldest museum in the West,” can now host traveling exhibitions and display about 20 percent of its permanent collection — up from about five percent before the expanded museum re-opened October 10 after a six-month hiatus. This means – finally — that the Crocker can shed its reputation as a stodgy repository of inconsequential art. It can now, for the first time ever, show its stuff. And it has plenty to show. Spread across two floors, and organized into various thematic categories (e.g. Pop, Latino, Funk, Bay Area Figuration, Abstract Expressionism), are works that represent a Who’s Who of Northern California art, much of it from the post-WWII period when the axis of cultural authority briefly tilted toward the West Coast.

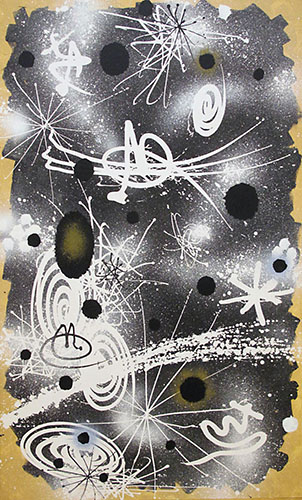

Highlights include major works by Wayne Thiebaud, Nathan Oliveira, Bruce Conner, David Park, Frank Lobdell, Christopher Brown, Paul Wonner, Michael Stevens, Suzanne Adan, Robert Arneson, Roy De Forest, Viola Frey, Manuel Neri, Joan Brown, Robert Hudson, Richard Shaw, Hung Liu, Marilyn Levine, Richard Diebenkorn, Robert Brady, Mike Henderson, William Allan, Deborah Oropallo, Robert Colescott, Peter Vandenberge, Martin Ramirez, Stephen De Staebler, Raymond Saunders, Enrique Chagoya, Stephen Kaltenbach and Peter Voulkos.

|

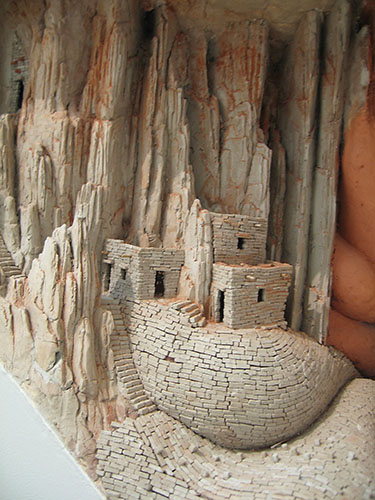

Then, there are a slew of wonders that defy easy categorization. Two that stand out are Charles Simons’ ceramic wall installation which mimics, at a vastly reduced scale, an Anasazi cliff dwelling. The other is Richard Notkin’s earthenware tile “painting” of George W. Bush, All Nations Have Their Moments of Foolishness which photorealistically depicts the 43rd U.S. president and his sins. It’s been in the Crocker’s possession for some time now, but it still stuns. So does Stephen Kaltenbach’s deathbed portrait of his father.

While the Crocker is not the contemporary art museum that many hoped it might become in its new incarnation, it’s not your grandmother’s Crocker, either. While the museum remains committed to mounting shows that reflect its current and historic strengths — drawings and prints; Flemish, Dutch, Central European and Italian art from the 16th to the 19th centuries; American Impressionism; early and contemporary California art; international ceramics; and art from Asia, Africa and Oceania – it also plans to keep at least a toehold in the present.

|

In January, for example, it will open Inferno of the Innocents, an exhibit by Vienna-born painter/photographer Gottfried Helnwein, whose depictions of inhumanity and violence are sure to ruffle feathers amongst the Crocker’s more conservative constituents.

–DAVID M. ROTH

Thanks for this review. I can’t wait to see the real thing!